On The Complete Cold Mountain:

Poems of the Legendary Hermit Hanshan

Written by: Peter Levitt

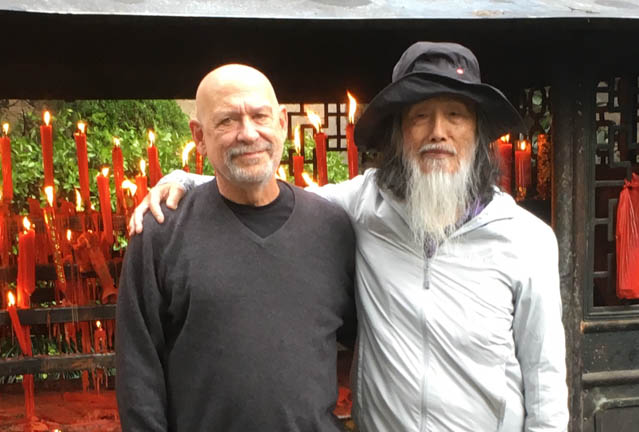

Kaz Tanahashi and me at Guojing Monastery in Southeastern China, where it is said that Hanshan went to meet his friends Shide and Fenggan.

Photos by: Kathy Shiels, Minneapolis Museum of Art, Shambhala Publications, Tokyo National Museum

In late June, 2018, Shambhala Publications published “The Complete Cold Mountain: Poems of the Legendary Hermit Hanshan,” translated from the Tang dynasty Chinese by Kazuaki Tanahashi and Peter Levitt. Of all the Chinese hermit poets from the late 7th century on, Hanshan (Cold Mountain) may well be the most beloved. Endorsements by Jane Hirschfield, Natalie Goldberg, Jon Kabat-Zinn, and Roshi Joan Halifax.

For more than half a century, my dear friend Kaz Tanahashi and I have considered the legendary Tang dynasty hermit poet Hanshan a true and personal companion of the way, despite the fact that Hanshan lived at least 1,300 years ago.

An unkempt Hanshan is shown sitting cross-legged, holding a brush.

In English, Hanshan means Cold Mountain, and it’s my sense that Hanshan took the name of the place he chose to settle down, far from what he called “the dusty world,” as a way of saying that who he was, where he was, and what he was, were just one thing. I find this a beautiful expression of interdependence and nonseparation.

Like many other readers, we were first introduced to the writings, legend and lore of this hermit poet through the English language translations of Burton Watson and Gary Snyder. Their work revealed that Hanshan left behind the dusty world of getting, spending and delusion so he could spend his life in the natural world with his heart and mind uninterrupted by distractions. By so doing, he put an end to what he called the “useless mixed-up thinking” that caused harm in his life, and in the lives of those he had encountered.

Even in those early translations, it was clear to Kaz and me that whomever this wild-man hermit poet may actually have been, (outside of the poems, there is no biographical record of the poet’s life,) the compassionate discernment, profound tranquility, unexpected insight, and occasional outrageous or scathing humor of his poetry touched a vein of life we deeply appreciated and shared.

As we gathered and translated all of the extant Hanshan poems for our project, we also found that what he left for us on the stone walls of his cave, or on nearby bamboo stalks, and occasionally on paper, appealed to us both in a way that was always fun, and often unspeakably touching and profound.

The cover of “The Complete Cold Mountain.”

Hanshan would wander the Tiantai mountain range in eastern China, before returning to his simple cave where he’d stir a handful of gathered vegetables into a thin broth soup beneath the large mossy cliff-edged rock above him. Neighbored by monkeys, tigers, and a constantly swirling mist, far up a mountain path of twisting switchbacks where no horse or cart could travel, our friend Hanshan would occasionally sit outside in the rare sun.

Winter and summer alike, his only clothes were a loin cloth or a simple robe. As a true person of non-doing, he would read a few passages of Laozi, whom he considered a rare companion. Sometimes he would play his simple lute, or discuss the profound principles of the meaning of life with a passing white cloud, which he always found to be faithful and true.

At other times during his mountain wandering he would find himself grasping his knees with his back against the walls of a treacherous cliff as a blustery and sudden storm came on, and wonder between chattering teeth how his life had become no different from that of a “lone flying crane.” But this did not stop him from also sitting through many an evening on the precipice in front of his cave, where he wrote in true wonder:

My mind is like an autumn moon

glowing purely in a clear blue abyss.

Nothing compares to it.

What could I possibly say?

Hanshan and Shide, another famous Chinese Zen poet, who often are portrayed together.

Due to the authenticity of Hanshan’s heart and expression, no matter what circumstances determined the activities of his day, the poems he wrote called to the Hanshan in Kaz and me in a voice that felt so familiar, it was as if it rose from our own breasts.

And so we decided to spend a few years translating Hanshan’s poetry with the hope that 21st century readers might meet him. We wanted to offer readers a chance to hear Hanshan’s voice in authentic translations that would bring the unique heart and vision of this poet across.

We hoped this compassionate wise meditator and seeker of the way could touch readers with his deeply human and humane understanding and heart. After all, we were just extending Hanshan’s invitation to join him in the place where he tells us:

Once I moved to Cold Mountain, everything was at rest.

No more useless, mixed-up thinking.

In idleness, I write my poems on stone walls,

accepting whatever happens like an untied boat.

and

My mind is like a solitary cloud, completely free.

Vast and unhindered, why would I search for worldly things?

It sounds so clear, so simple, so good, who would not want to join him where

With a bed made of thin grass

and the blue sky for my cover,

I rest my head happily on a stone pillow

and follow the changes of heaven and earth.

But, it may not be as easy as one thinks to simply pack up one’s cares and woes and take off for Cold Mountain’s climes. After all, where is the map to get there, when Hanshan says,

You ask the way to Cold Mountain,

but the road does not go through.

In summer, the ice is not yet melted,

the morning sun remains hidden in mist.

How can you get here, like I did?

Our minds are not the same.

When your mind becomes like mine,

you will get here, too.

He warns us that the way may not be as straightforward as we would prefer.

Go ahead! Make fun of the way to Cold Mountain,

where there’s not a trace of horse or cart.

It’s hard to remember valley switchbacks

below layer upon layer of so many peaks.

Dew weeps on a thousand kinds of grasses,

winds sing through the pine.

Lost now on my path,

Shadow, tell me, which way should I go?

Peter Levitt and his wife, poet Shirley Graham.

And then there is this: Can one fully and completely have access to the wholeness of their heart, and still completely leave the world of dust behind? Is there a place that will prevent a caring heart from thinking of those friends who have passed on in this impermanent, floating world, so that as we sit facing our lone shadow on the cave wall lit by a solitary candle, we can prevent “two threads of tears [from] streaming down?” And do we really want to?

As we wander the streets we pass through alone, seeing the world we hoped to have left behind, don’t we want our caring hearts to notice that

Rich people meet at a tall building

decorated with shining lamps.

When a woman without even a candle

wants to draw near,

they quickly push her away,

back into the shadows.

How does adding someone diminish the light?

I wonder, can’t they spare it?

Isn’t it crucial, especially these days, that we do share the light? As we enter the world of Cold Mountain’s poetry, we may find there is not a contradiction between the man who wants to leave the dusty world to enjoy his joyous rambling, and the one who has written many poems to encourage others to stop creating a hell on earth for themselves and others. In the end, despite all appearances and what we might initially think, his invitation remains:

People nowadays who see Cold Mountain

all say I’m crazy.

They don’t look at the face

above this humble robe.

They don’t understand what I’m saying,

and I don’t speak their language.

All I can say to those who pass by:

“Try to come to Cold Mountain.”