Reflections on a Weekend of Radical Dharma

Written by: miscellaneus

Reverend Angel Kyoto Williams brought joy and support to people at the radical dharma weekend

Photos by: Genevieve Hicks, Denis Martynowych

Reverend Angel Kyodo Williams, sensei, the second of only four black women recognized as teachers in the Japanese Zen lineage of Buddhism, visited Seattle this December to offer a weekend of radical dharma.

Reverend Williams based her offering on the book “Radical Dharma,” which she co-authored with Lama Rod Owens and Jasmine Syedullah.

Co-hosted by 8 Limbs yoga, Rainier Beach Yoga, and the Mindfulness Community of Puget Sound (MCPS), the weekend offered participants the opportunity to “wake up from the habitual ways they and their members reproduce and sustain exclusion.” It suggested they instead explore a “’new dharma” that deconstructs rather than amplifies systems of suffering.”

Reverend Angel taking questions from those attending the Saturday workshop at The Summit on Capitol Hill.

As a teacher, author and trainer, Williams engages Buddhist wisdom and practice to cultivate outer change through inner change. In recognition of her work toward “a presence-centered social justice movement as the foundation for personal freedom, a just society and the healing of divisions of race, class, faith and politics,” Williams was one of the four to receive the first “Enlightened Society Award” from Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche, leader of the international Shambhala community.

Mindfulness Community of Puget Sound (MCPS) is a south Seattle-based sangha practicing in the tradition of Thich Nhat Hanh. During a January Monday night MCPS service Genevieve Hicks–the MCPS sangha member who co-organized Williams’ “Weekend of Radical Dharma in Seattle,”–led a discussion about the weekend.

Diane Hetrick:

“As we do this work, we need to hold a polarity, where we offer ourselves forgiveness for all the things we didn’t know or see about oppression, and a willingness to enter into the pain of it now.

The oppressive system of white privilege and how to step out of it is ‘a mess.’ We’re going to have to ‘not know’ and be uncomfortable for a long time. We need to learn how to tolerate/sit with not- knowing and discomfort.

It’s useful to remember while we experience this that people have been experiencing the pain and confusion of this system for hundreds of years. It’s also useful to ‘fortify ourselves’ – create steadiness for ourselves with the messiness of this work. Learn to offer ourselves self-care. Many people, particularly people of color, were intentionally taught not to take care of themselves.

Reverend Angel attracted a large and diverse gathering to her teachings.

The anger of people of color toward whites makes sense. And, it’s important to remember it’s not personal. For white folks, when you see something wrong and know you should do something, but are unclear what that is, there is no magic answer.

But you have to risk yourself. This effort has a cost. It’s not possible or viable to do something and still stay safe and be sure it will go your way. (And we live in a culture that tells us to stay safe and not risk ourselves). For people of color, just leaving the house each day can be a risk.

Only having conversations about race from a ‘seat of love,’ doesn’t mean it’s all ‘nice.’ The intention is to be rooted in love – including self-love – and to not harm or hurt anyone.”

Sol Riou:

“Sitting in the presence of Rev. Angel Kyodo Williams was a rare opportunity of safety, which allowed me to experience my feelings about racial oppression. Even though I consider myself well-informed about our country’s racialist history, Rev. Angel humbled me with new insights.

She modeled what she calls coming from ‘a seat of love,’ which brought sadness rather than any sense of shame for my social situation of having white privilege. White privilege is invisible to whites, and so throughout my life I have instinctively colluded with this oppressive white culture I have so passionately believed I was fighting against.

Many others in the racially-mixed group taking part in the workshops shared from their hearts’ personal experiences of racial oppression. Being in such authentic company left me with deep grief about how white privilege wounds us all.

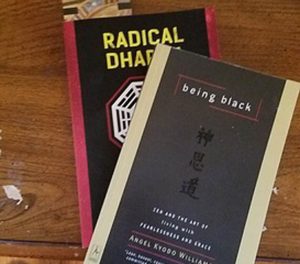

Reverend Angel wrote “Being Black: Zen and the Art of Living with Fearlessness and Grace.” She collaborated with Lama Rod Owens and Jasmine Syedullah to create “Radical Dharma: Talking Race, Love and Liberation.”

Most useful for me was a metaphor that Rev. Angel shared, about white privilege being like a river ending in a waterfall.

The river is the oppressive system of white privilege that has indoctrinated us to want to belong. We get swept along without thinking. We fear the consequence of being shamed, blamed or excluded if we stand up and resist being a faithful member of white culture. This river ends in a waterfall, landing on the backs of people of color.

With awareness we can ‘be in choice’ about whether or not we participate in these oppressive systems or actions. Instead of going with the flow of the river, we can ‘swim upstream’ or ‘stand firm,’ and in this way not add to the weight of the water falling upon people of color.

Rev. Angel challenged me personally, and our white sanghas, by saying that unless we are healing ourselves from white privilege we cannot offer a safe space for people of color. It is not that I need to be embarrassed or ashamed of my ignorance, but I do need to take responsibility for it. I can learn concrete actions to be more compassionately connected to life — my own and others.

My personal meditation practice has given me profound relief from an undisciplined mind that brought me relentless stress and self-criticism. Yet enlightenment is developing the mind of love, which is more than personal relief. It is total liberation, which can only come from looking deeply into how we collude with white privilege.

The ability to heal from the shame, blame and exclusionary wounds of white privilege will only come from the ability to no longer participate in this system of shaming, blaming and excluding others as we grasp at relief from our own suffering. Our sanghas can be a welcoming source of comfort for our personal struggles, and they can also provide a brave space for us to struggle with our social disease of racism.”

Reverend Angel and assistant Svani Grevemeyer at Sati Sphere, a collaborative South Seattle practice and housing space for Buddhist practitioners working toward social justice.

Cristina Mullen:

“Reverend Angel called us into our wholeness. She invited each of us to investigate the nature of the system that we live within and that we help to sustain. Like all systems, white supremacy resists change. Reverend Angel acknowledged the pain we all feel when we are in contact with the pain of the world, in this case, specifically the pain of white supremacy and how we are damaged by it–people of color and white people.

I was impressed by her honesty. She spoke directly of the truth of white supremacy, fragilizing no one. This felt incredibly humanizing to me. During the weekend I was also honored to be in a community with people of color, and recognized their willingness to be there with white people as a gift I had not personally earned.

The work our sangha is doing to collectively look beneath the veil of racism feels so important to me personally.

People of color in our community have been vulnerable enough to tell us they do not feel safe enough in our dharma discussions to bring their whole selves.

I am grateful — both to them and to others within the sangha, who have organized our recent discussions about social justice. I am also grateful to those who organized this workshop for all of us to see these truths, and our practice of breathing, so we can stabilize ourselves in the midst of the confusion and pain.”

Denis Martynowych:

“Rev. Angel Kyodo Williams spoke about how central, vital, and necessary overcoming racism is to the liberation of the heart/mind.

She said if your practice doesn’t engage you in this area, change your practice, because it will not lead to liberation. The way she spoke about this centrality was inspiring for me.

I also appreciated that she acknowledged how difficult it is to swim against the stream of internal and external racism. When it is difficult, there is a tendency to blame oneself, blame others, or turn away.

The dominant social and structural patterns that hold racism in place are glued together by blame, shame and self-judgment. Mindfulness can help me notice these tendencies in my mindstream, and turn instead to thoughts and actions that are more useful.

Making an effort to study the history of racism over the past decades, centuries and millennia is another key way to understand how deeply embedded structural patterns of racism are and why this vital work is difficult. It is also a powerful way to untangle more of my “self” from the effort and see the impersonal flow of causes and conditions more clearly.

It is my responsibility to uproot racial biases in myself and racism in my community, but it is not my fault that racism exists or that I get confused.

During this weekend I also learned about the importance of being visible as an ally, especially in white-dominated spaces. Meditator-types and introverts, like me, can lean towards being quieter and more reserved than is useful. When people of color are in white-dominated space, they can’t automatically tell who is safe or safer without some acknowledgment, assurance, interaction or visible sign. Because white-dominated space is set up for the ease and comfort of white people, white people are often blind to how different and unsafe the same space is experienced by people of color.”