Seattle Betsuin Brings New Light to LGBTQ Issues

Written by: Tara Tamaribuchi

Rev. Kiyonobu Kuwahara, Center for Buddhist Education, (CBE, Buddhist Churches of America), giving opening remarks.

Photos by: Irene Goto

More than 90 people gathered in November, for a daylong seminar on LGBTQ identity and Shin Buddhism, at Seattle Betsuin Buddhist Temple.

Called “Rainbow of Infinite Light,” the Nov. 18 event was organized by the Seattle temple and by the Center for Buddhist Education of the Buddhist Churches of America. The purpose was to better understand the LGBTQ community and its intersection with Buddhism, and what Buddhists can do to create conditions for inclusiveness and advocacy.

The event drew a large crowd to the main hall of Seattle Betsuin Buddhist Temple.

Over the last several years the Buddhist Churches of America and the Center for Buddhist education have offered similar seminars in New York and Berkeley.

The Seattle featured a personal story by mother and transgender son, Marsha Aizumi and Aiden Aizumi; an academic talk on LGBTQ and Buddhism by Rev. Dr. Jeff Wilson, and a local LGBTQ Buddhist panel to share experiences and views.

Young Northwest Buddhists celebrate coming out

The panel of LGBTQ Buddhists from the Seattle area, moderated by minister’s assistant Elaine Donlin of San Francisco Buddhist Church, shared stories of coming out, how Buddhism guided them, and the need for LGBTQ advocacy and understanding. They asked that their real names not be used.

One transgender woman said a dharma message helped push her to live as her true self.

The Aizumi family poses with Seattle Betsuin’s Zumoto/Ko family.

“The dharma is all around us and when are we going to receive it?” she asked. “I take it as a step in what direction do you want to go? When am I going to take that step from presenting myself as a man to presenting myself as woman? That little phrase from the dharma has helped me get there.”

The gay son of Thai immigrants shared a story of “love in action,” when he came out to his mother. His mother then told each of her family members that if they didn’t accept him, then they couldn’t be in his life.

“Love is an action,” he explained. “It is something you go out and do. You have to go out and create the conditions for it. My mother, she created the conditions so that when I came out, I didn’t have to experience some of the things that others experience.”

Rev. Dr. Jeff Wilson presenting “A Queer History of Buddhism.”

A Seattle temple member explained Buddhism helped him reconcile with his parents, who had difficulty accepting him as gay.

“They acted out in fear, out of ignorance,” he said. “I was able to forgive them, and I don’t think my heart would be able to be ready for that without Jodo Shinshu.”

The Thai Buddhist said the LGBTQ community needs more than allies for support.

“It’s great to be an ally and support folks and accept folk into your community, but I’m not really looking for allies right now…” he said. “I’m looking for accomplices. I’m looking for people who say ‘I see you live in an uncomfortable world, and I’m going to come out with you and make this world comfortable for you.’”

“When we have to go out of our way to do additional work, it’s asking people who are already hurt by societal norms to have to defend ourselves,” the man said. “Step up and create the conditions so that we don’t have to.”

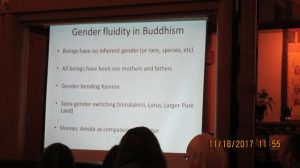

A slide from Wilson’s talk.

The Aizumi family learned to celebrate sexual identitity

California resident Marsha Aizumi said she realized, after adopting Aiden Aizumi from Japan, that the child, assigned from birth as a girl, might be different.

“He has always been my son, I know that now,” Aizumi said, showing a slide of Aiden in a dress. “He always wanted to be in boy clothes, do boy things. We thought of him as our little tomboy.”

“Elementary school years were uneventful, other than marching to the beat of my own drum,” Aiden recalled. “My peers didn’t engage with me in a way that made me feel different.”

Marsha Aizumi, Aiden Aizumi, Rev. Dr. Jeff Wilson, Rev. Elaine Donlin, and Rev. Kiyonobu Kuwahara, after the seminar in front of Seattle Betsuin’s Amida shrine.

In middle school the boys shut Aiden from their group, and Aiden had nothing in common with the girls. In high school the social pressure of fitting in grew worse. His only solace at school was playing girls’ golf, where no one cared how he dressed, and he only cared about playing to win.

Aiden was unaware of various gender identities. He decided to come out as a lesbian in his sophomore year. The school was unprepared to handle the daily bullying Aiden experienced.

“I was very easy to pick on,” he shared. “I was always by myself. I was having a lot of anxiety and panic attacks.”

By senior year, Aiden stopped going to school and finished through independent study at home. He lived in a limbo state, missing out on normal teenage life and suffering from agoraphobia, the fear of leaving home.

But his life began to turn around after he learned about gender identity. When he told his mother he was transgender Marsha was unfamiliar with the term, but she recognized she needed to conquer her learning curve quickly.

The planning committee, for “Rainbow of Infinite Light: LGBTQ and Shin Buddhism,” worked hard to bring the event together.

“I didn’t know about it, but what I did know was that if I didn’t get it right, I would probably lose my son,” she explained. “I was going to figure this out so I was not going to lose my child.”

Aiden was turning 21, and was going through the process of physically becoming a man. His parents grieved the loss of their daughter while celebrating their son.

“I saw the light come back into my child’s eyes,” Marsha said. “When we celebrated his 21st birthday, it wasn’t because he was turning 21. I was celebrating that my child was still alive.”

Marsha talked about the culture of shame for Asians, and the possibility of Alden bringing shame to the family for being LGBTQ.

“I learned since that it is not a choice for our LGBTQ children,” she said. “It was up to me as a parent. Was I going to stand by him and walk this path, or was I not?…For me, I realized I was going to honor my family best by standing by my son.”

“Today I feel that shame has turned to pride,” she said. “I am so proud of my son…..I’m proud of myself that I’ve been able to overcome some of the fears that I had and tell people how proud I am of Aiden.”

Marsha shares this story in her published book, “Two Spirits, One Heart: A Mother, Her Transgender Son, and Their Journey to Love and Acceptance.” You can find out more about the Aizumi family here.

Rev. Dr. Jeff Wilson and Buddhist “queer history”

Rev. Dr. Jeff Wilson, associate professor of religious studies and east Asian studies at Renison University College, spoke about Buddhist “queer history” and Shinran Shonin as a queer icon.

(Shinran Shonin, a 13th century Japanese monk, was the founder of the Jodo Shinshu sect.)

Wilson, a Jodo Shinshu Hongwanji-ha minister, explained the term “queer” has various connotations, from pejorative and harmful, to one of political progressiveness and solidarity.

Wilson ascribes to the latter. In his queer studies theory he describes “queer” people as “people who don’t fit into dominant positions, and therefore they call those dominant modes into question. This often results in marginalization or oppression.”

Wilson asked if there was something queer about Buddhism itself, as a religious system. He argued that Buddhism is “queer” in challenging Western spirituality. In classical Buddhist society monastic and lay communities are mutually dependent but are separated only by sexuality, he said. While all forms of sexuality are forbidden in monasteries, all types of sexuality are treated as equal.

Historically LGBTQ people haven’t been actively persecuted in Buddhist societies, he said.

Today he sees Buddhist treatment of LGBTQ people ranging from being made illegal in some former British colonies, to choosing LGBTQ persons to lead temples in other regions.

While Wilson finds many modern-day Buddhist communities are LGBTQ-ignorant, he also called the current era a queer Buddhism golden age. He pointed to many information and support resources for the community, citing the website www.transbuddhists.org, and the “Queer Dharma: Voices of Gay Buddhists” book series by Winston Leyland.

Wilson calls Shinran Shonin a queer Buddhist icon because he was neither a monk nor a layman, therefore living outside the organizing principle of Buddhist society.

“When he failed to fit into these categories he was absolutely what we would define as queer with all the possible discrimination and labeling by society,” Wilson said. “He is absolutely in-between, he is a gender criminal.”

Shonin then took this to the next level.

“He then founded a tradition of married monks and nuns,” Wilson said. “All of his followers become gender criminals. By the standards of the rest of Buddhism, we are gender queer.”

Wilson brought attention to when Shinran Shonin recited the nembutsu for 100 days at Ryokkaku-do temple in Kyoto, and saw Bodhisattva Kannon manifested as Prince Shotoku on the 95th day. Prince Shotoku announced, as it was Shinran’s karma to have sexual contact with women, that Prince Shotoku would become Shinran’s wife, to help guide him through life and lead him to the pure land.

“So Shinran’s wife was a dude,” Wilson revealed. “If you just look at the facts of this, this is significant — Kannon is famous for gender-bending, so there is nothing odd about this in the Buddhist tradition. So, Shinran went on to carry the tradition and believed his wife to be a manifestation of Prince Shotoku.”

Wilson touched on the gender fluidity in classical Buddhism, where living beings go through life after life for infinity, and can inhabit any possible body or social position.

“Regardless of your current identity, you have been every other possibility,” he explained. “Assuming you aren’t headed right to Buddhahood, you are headed to all these situations again.”

Wilson touched on actions from the BCA in advocating for LGBTQ, from marching in pride parades, to the bishop asking the Boy Scouts of America to not ban gay scouts. Since the 1970s, BCA ministers have officiated same-sex marriages. Because Japanese Americans founded the BCA and were sent to internment camps during World War II, ministers today argue this is a reason why BCA members should support discriminated groups, including LGBTQ.