Meditation over Medication:

An Alternative Approach to Military Healing

Written by: Jamyang Dorjee

Vernon Vernon Kellnhofer, an 18-year veteran, found meditation a creative way to work with the traumas of his service in war zones.

Photos: Courtesy Joint Base Lewis-Mchord.

(Editor’s note: Joint Base Lewis-McChord, the U.S. Department of Defense’s largest West Coast military base, deploys cargo aircraft and Stryker brigades to points of conflict around the world. The base, halfway between Seattle and Olympia, also is home for 40,000 enlisted people, some of whom are turning to Buddhist meditation as an antidote to the inner trauma of battle.)

Soldiers Vernon Kellnhofer and Maria Guzman both deployed to Iraq, and both came back missing something inside.

And both found resolution, and a way forward, by turning within through meditation.

Born in El Salvador, Guzman found her way into Joint Base Lewis-McChord Buddhist services “looking for peace,” she says.

The altar at the Thursday evening Buddhist practice session at JBLM.

Guzman had deployed to Iraq in 2009, where she set up mobile hospitals, and where reality was often raw and painful.

“I saw things, as a human being it’s not normal to see such things except maybe in movies,” she said. “But this is real and though it’s not my fault, I can’t help but feel helpless. It’s difficult to get over all that.”

With an emptiness in her heart she had no answer for, Guzman said that when returned she found that people often were pretending to listen to her, but not really hearing.

She turned to meditation as a way to cope with anger that kept arising, and that wasn’t fixed, but just tamped down, by medication.

“With meditation I don’t feel the anger,” she said. “I realize I need to work with myself first.”

While she was brought up in the Catholic Church, she said that the Buddhist meditation group became her sanctuary.

“In the church I didn’t feel comfortable because of what I wore and how I looked. I wear sweatpants and stuff and pretty much kept to myself. It’s who I am,” she said. “So I went looking for something else.”

Kellnhofer’s story is in a way similar, of a person who saw too much during combat, and who now is using the same bravery that sustained him, to find an inner and sustainable way to cope with the trauma.

A fleet of Chinook helicopters, here in a rescue exercise, is based at JBLM.

Kellnhofer, 5’ 9” and 190 pounds of muscle, is clean-shaven, tough and imposing, looking every bit the soldier he is.

As an 18-year veteran of the U.S, Army, Kellnhofer is a non-commissioned officer at Joint Base Lewis-McChord who is an expert in some of the deadliest tools of war. Technically he’s a CBRN, which stands for “Chemical Biological Radiological and Nuclear.”

What this means is that Kellnhofer trains National Guard Reserve soldiers how to detect when they are under a biological or chemical attack, and to protect themselves and treat any victims. This is heavy stuff, which wears on a person.

Deployed three times to Iraq, like most soldiers Kellnhofer suffered from the physical and emotional trauma of his work and environment. Mental stress and post traumatic stress disorder followed, and led him predictably into the world of medication for treatment.

But as a practical and creative man, Kellnhofer thought there had to be a better way than just depending on medication, and so he set himself a goal to find it.

Kellnhofer recalled reading about meditation and the concepts and practices of Buddhism on the internet. He began meditating on his own a little and noticed how it helped him.

Kellnhofer in his military uniform.

That latent interest in meditation…fueled by a recent stint of active duty in Korea this past March..brought Kellnhofer back from his wanderings wondering.

His curiosity led him to explore the chaplaincy page of the JBLM website, to his surprise saw a Buddhist service.

He showed up…a bit nervous, not knowing what to expect. Born and raised Catholic, it was a wandering of a different kind.

Joint Base Lewis-McChord, commonly referred to as JBLM, is home to one of the largest “Religious Support Organizations” in the United States Army, with almost 95 Unit Ministry Teams stationed at Lewis Main, Lewis North and McChord Field.

The JBLM Chaplain oversees and operates nine chapels, and performs and provides a variety of religious services for the soldiers and airmen stationed at the base. Sermons range from liturgical, traditional, gospel and contemporary, and the teams offer Jewish, Islam, Buddhist and Wiccan services.

In a stark room bare of anything but a little statue of the Buddha, the small JBLM Buddhist sangha gathers every Thursday evening at 5:45PM.

Ann Tjhung, an ordained Zen Buddhist priest, leads the Buddhist practice at JBLM.

Led by Ann Tjhung, an ordained Zen Buddhist priest, the group usually begins with 30 minutes of meditation, followed by a brief dharma talk sometimes given by Tjhung or by another member. Then a conversation follows.

Last week she asked Kellnhofer to give the talk.

“I was a bit surprised and a little afraid but I enjoyed it,” he said. “She (Tjhung) is a bit like that, easy-going but knows when to push you.”

Like Kellnhofer, Tjhung’s introduction to Buddhism also began via the internet, and after trauma.

She “began practicing seriously,” she said, after she lost her then-19-year-old son, a U.S. Marine, to a car accident in California about five years ago.

Via JBLM’s counseling for the grieving, she started attending the Buddhist services then offered by Ajahn Malasarie, a Thai Buddhist Monk.

Tjhung began increasingly began taking an active role in the sangha under Ajahn Malasarie’s tutelage.

And then he asked her, much to her surprise and despite her not being an ordained chaplain, if she would take over the service.

Chaplin Captain Somya Malasri had received a scholarship and was moving to Virginia, but he trusted that Tjhung had deepened in her practice enough to take over.

“It was quite an honor,” Tjhung said.

JBLM personnel risk their lives in missions on aircraft like this C-130 Hercules, on a training mission simulating rescue of earthquake visions.

The weekly service is open to all, and is free for people on the base.

“Attendance is pretty small most of the time,” she said. “A lot of Americans don’t really understand it, and because the practice requires some work and effort, people tend to shy away from it. It requires some self-control, to be able to sit down…sometimes might seem like it has no value, but it is huge.”

Because army personnel are always on the move, people are always passing through the JBLM sangha.

Through the year Tjhung has seen both young and old, military personnel as well as civilians and their families. Some attend meditations for six months but then they get relocated, reassigned and move on.

“Everybody seems to take something positive from it,” she said, adding that she tries to keep in touch with many of them through their Facebook page, and to share articles and reading material through that.

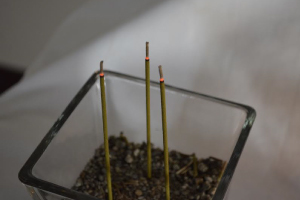

Incense burning during the Thursday night sit, symbolizes the peace of practice.

Like Guzman, Kellnhofer said part of the power of the Buddhist practice comes from how it enables him to work on himself, how it gives him inner tools he can use.

“I don’t like to downplay any religion but I don’t see them practicing anything,” Kellnhofer said. “They dress up nice for one day a week to be a better person.”

He added that it was a practice he could do, and that it started with him being exactly himself.

“There is a reason why it’s called ‘Buddhist practice,’” he said. “It’s a practice. I’m not perfect at it but I keep trying to get there. It helps me a lot. I feel I’ve made a few improvements in my personal life and generally found that nothing comes out of it but good.”

It has been about five months now that Kellnhofer has been off medication and he is convinced that’s because of his meditation practice.

“I know it was the meditation. It’s gotta be,” he said. There’s a hint of humble triumph in his voice.