Sanje Elliott, Western Thangka Painter

Written by: Jacqueline Mandell

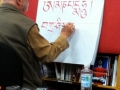

Sanje Elliott painting during the Tibet exhibition at the Portland Art Museum, 1993.

Photographers: Roger Edwards, Jacqueline Mandell.

Just months ago Portland-based Sanje Elliott published what may prove to be one of the best how-to books on Tibetan calligraphy, capping a career of art, music and dharma practice stretching back over more than four decades.

Elliott took two years to write his book, “Tibetan Calligraphy,” at the request of Wisdom Publications.

The detailed guidance in this book is a great contribution to dharma students wishing to improve their visualization of key letters and seed syllables.

The book guides Tibetan language students who wish write in the Tibetan alphabet in the same way it was originally written. In particular it shows readers how to use a flat-edged pen to create the thick and thin strokes so essential to Tibetan script.

At 81, Elliott continues a rich creative and dharma life. At his home studio he continues to teach Tibetan-style thangka painting, the colorful renderings of Tibetan meditational deities on cloth scrolls, and he also paints commissioned thangkas.

Elliott also creates modern art, and in Portland has recently shown some of his new paintings, which use mantra as the basic form.

I first met Elliott in 1972 in Bodh Gaya, India, the place of the Buddha’s enlightenment. When I later moved to the Pacific Northwest, I was delighted to find that Elliott, a native Oregonian, was living and teaching in Portland.

How does someone who did commercial art in high school, who graduated from Lewis & Clark College with a bachelor’s degree in fine art, and who later studied at The Academy of Fine Arts in the late 1950s in Florence, Italy, turn himself to learning thangka painting?

Elliott’s first painted thangka, which he completed in 1975, hangs at the Kagyu Changchub Chuling Buddhist center in Portland. And years ago, in Santa Fe, N.M., I was mesmerized by his deity paintings on the inner walls of a stupa at the Kagyu Shenpen Kunchab Buddhist Center.

I always wondered how he had learned to create sacred images with such impeccable detail, precision and visual luminosity.

Earlier this year, on a chilly Sunday afternoon, I had the opportunity to share lunch with Elliott at a Portland Shenzhen restaurant. While we enjoyed delicious Chinese food and sipped tea, he shared his round-the-world journey into Buddhism, art and music. His journey is an interweaving of cultures and continents.

Elliott’s attention turned toward the inner life unexpectedly, while he was studying in Italy.

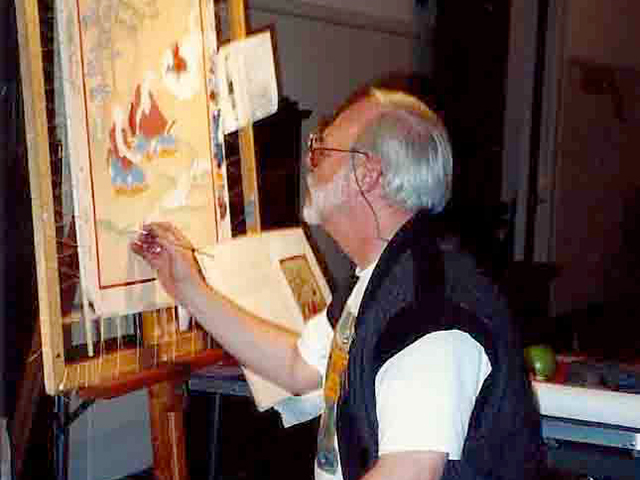

Sanje Elliott painting in his studio.

He had gone to visit the villa of the famous art historian Bernard Berenson, outside Florence. While driving home, stopped at a traffic light in a village, he experienced a major epiphany of interconnectedness with all living beings.

A further opening came later in Germany, when he found himself writing the phrase: “Once upon a time there was a painter who wanted to paint his gods.”

Elliott then waited for the next inspirational step to reveal itself.

After returning to Portland in 1963, he set up a studio and began painting large abstractions.

Six years later he had his first experience of Buddhism through a seven-day sesshin with Joshu Sazaki Roshi, and continued zazen for two years. Then a friend loaned him “A Jewel Ornament of Liberation,” a book by great 12th-century teacher Gampopa, and Elliott suddenly knew he had to find a guru in the lineage of Milarepa, Gampopa’s teacher.

Elliott abandoned his studio, bought an around-the-world air ticket, and set off for India.

Elliott’s journey took him through Europe, and while touring Morocco he had a vision of ‘light’ around England.

With the help of an oracle he went to Samye Ling in Scotland, where he met his guru Kalu Rinpoche, who gave him refuge and bodhisattva vows.

Soon after Elliott journeyed to Sonada, India, the home of Kalu Rinpoche, to receive further teachings.

Sanje Elliott recently, at a Portland Chinese restaurant.

While in the Darjeeling area he went to Rumtek Monastery to meet the 16th Karmapa and Sister Palmo in Sikkim, and there he met TaJa, an elderly thangka painter whom the 16th Karmapa brought with him from Tibet in 1959. This was the first time Elliott was introduced to a thangka painter and attended a class.

Elliott began to take photos of thangkas out of general interest in the art, but it wasn’t until 1974 that he began to study thangka painting, with the late Glen Eddy, who had been trained by Tibetan masters.

Elliott taught thangka painting at Naropa Institute in Boulder Colorado for five years, before opening his Portland teaching studio.

In addition, Elliott also studied Tibetan language and Tibetan calligraphy, starting in the Darjeeling area of India, where Tibetan Lama Tshundu Tsangpo showed him how to do the correct strokes for each Tibetan letter.

During 1980-81 Elliott studied Tibetan language privately with different lamas in the Kathmandu Valley. As he became proficient in Tibetan calligraphy, he saw a need for a good book to illustrate and inspire others.

In the early 2000s Elliott attended a calligraphy weekend at the Great Vow Zen Monastery in Clatskanie, Ore., where he met master calligrapher Kaz Tanahashi. There he also met Josh Bartok, the head editor for Wisdom Publications, who asked Elliott to create the just-published Tibetan calligraphy book

With myriad influences, Elliott is also a musician and pianist. As is the case with all of his lifelong talents, Elliott started learning music early and founded his own eight-piece dance band in high school.

Several years ago Elliott played classical piano for a wedding ceremony I performed in southern Washington for dharma practitioners. His music brought a radiance of love and delight to the ceremony.

And every other Saturday evening Elliott plays piano at the Heathman Lodge’s Hudson Bar and Grill in Vancouver, Wash., just as he years ago regularly did at the former Hotel Soaltee Oberoi in Kathmandu, Nepal, and later at the Westin St. Francis in San Francisco.

Portland is the proud home of Sanje Elliott, a rare gem of a person.