UW Study: Kids of Mindful Parents Share More

Written by: Bob Baumgartner

Associate Professor Jessica Sommerville, who received her doctorate at the University of Chicago, next to a computer that tracks children’s eye movements during tests.

Photos: University of Washington, Steve Wilhelm.

Kindness does count, and mindfulness does matter, according to a study by the University of Washington psychology department.

The study followed two groups of infants and their primary caregiver parent over a three-month period, to determine how parents’ mindfulness practice affected their children.

The parents in one group received mindfulness training that included meditation and practices for observing the workings of the mind, rather than getting caught up in them. Parents of infants in the other group did not receive mindfulness training during the study period.

The study found that the infants of parents who received mindfulness training shared toys twice as often as the infants whose parents did not receive mindfulness training. Furthermore, the more the caregiver practiced mindfulness, the more the child was willing to share toys with others, said the study’s lead, UW Psychology Professor Jessica Sommerville.

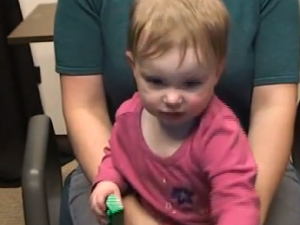

In this test, a child with a toy is given an opportunity to share that toy with another.

“I think it’s really exciting,” Sommerville said. “One of the things I really like about the findings is that, while societally there’s a big push for parents to spend as much time with kids as possible, this aspect of child well-being ties into how well parents are taking care of themselves.”

As a parent, taking care of your own mental well-being has an “important impact for your child,” Sommerville said.

“In our work, we think that mindfulness works by increasing empathy in parents,” she explained in an email. “We hypothesize that these changes in empathy have downstream consequences for kids, because they lead parents to change how they behave with kids and in front of kids.

“Specifically, we think that the increase in empathy results in parents being more ‘other oriented,’” she added. “This may have direct effects on infants.”

Children of meditating parents may learn by observing more helping and sharing behaviors by their parents.

Sommerville said she arrived at the topic of her research through a “backward” sort of process. Typically, people who would like to improve an infant’s prosocial behavior would focus on the infant. She decided to focus on the parent.

“We thought one way to go would be through the parent because the parent is the one consistent factor in a kid’s life,” she said. “We thought, ‘If you can affect change in the parent, it should have a long-term positive impact on the kids.’”

Sommerville plans to submit her findings to an academic journal in June.

Children whose parents did mindfulness practice shared their toys more often.

The study included 44 primary caregiver parents and their infants, who were all nine months old at the start of the three-month project.

The mindfulness “intervention” training consisted of one two-hour session per week, for 10 weeks. It included questionnaires designed to gauge how well the parent took on the perspective of another person, such as someone in a state of distress, Sommerville said.

Parents were taught to meditate by turning their attention inward, and by observing their thoughts, emotions and feelings as an onlooker, without getting attached to these experiences.

“Just observe the sensation without having your mind run away from yourself,” instructor Lisa Hardmeyer-Gray told them.

After the parents practiced mindfulness for 10 weeks, their children were tested at the UW research lab in carefully controlled video-taped sessions in which there were toys and other children. Psychologists wanted to know whether the mindfulness of the parent would affect the willingness of the child to engage in behavior that helped other people, what they call “prosociality.”

Finding that the mindfulness of the parent is a predictor of the child’s willingness to share is one result of a growing body of research on mindfulness. Sommerville said that mindfulness is a “hot topic” in the field of developmental psychology, because it “seems it can be incredibly beneficial.”

She plans to present her study, “The Impact of Parental Mindfulness Training on Infant Prosociality,” at the 2015 Mindfulness Research Conference. This conference is to be at the Bell Harbor International Conference Center in Seattle, April 17-18.

Jessica Sommerville, with some of the toys her program uses to interact with children.

Sponsored by the University of Washington Center for Child & Family Well-being, the conference will host local and international researchers presenting findings on mindfulness in relation to a wide variety topics, including trauma healing, at-risk youth, compassion, parenting, and education.

Besides the infants and their primary caregiver parents, the study involved about 20 people who served in a variety of roles, including lab managers, undergrads, grad students, and even post-docs eager for some research experience.

One of the most difficult, painstaking tasks – one that still remains to be completed – is that of coding the parent-child interactions. It must be done by people with very specialized training, who observe the videos slowly, frame-by-frame, to determine how to code the interaction that occurs.

Sommerville said that while mindfulness is a hot topic, this sort of research, which involves developmental psychology and moral development, is neither easy nor cheap. She estimates the cost of her study at about $200,000.

The research was funded by the University of Washington Center for Child and Family Well-being, as part of its “mindfulness initiative,” and by the John Templeton Foundation. The latter, based in Pennsylvania, supports research on the intersection of science and spirituality.

For Sommerville, a psychology professor at the University of Washington since 2003, the study marked her first foray into mindfulness research.

“By virtue of this research, I had to learn about mindfulness,” she said. “I think there’s value in the idea of being present and not letting your mind run away with you.”