Sitting on the Cushion, Not Behind Bars

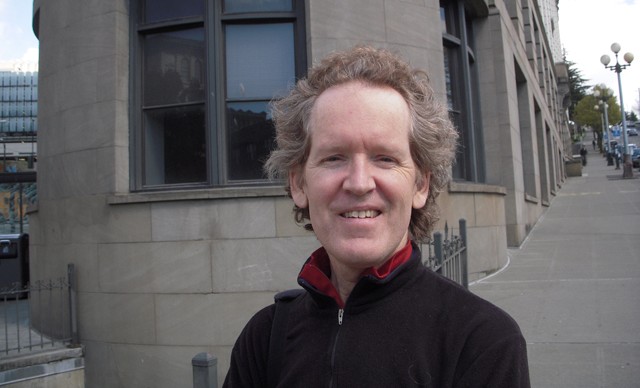

Written by: Jordan Van Voast

Jordan Van Voast finds that meditation can be an important tool for people seeking a better path in their lives ahead.

Five women meditating around the table in a small Seattle conference room are getting a second chance – an alternative to incarceration.

They’re also getting a chance to know themselves better through meditation practice, and perhaps avoid the choices that got them in trouble with the law in the first place.

I think people are touched by it…but it’s hard to measure. Even under the best of circumstances, meditation is easy in theory, but challenging in practice. The barrel is filled one drop at a time.

The five, sitting in the relatively stark surroundings of a government building, are participating in the King County Community Center for Alternative Programs, or CCAP. The program requires convicted people to participate in weekly programs, intended to help them learn to conduct their lives in ways that will keep them out of jail in the future.

The meditation classes at CCAP grew out of an existing collaboration between the Tzu Chi Foundation and King County.

Tzu Chi, a global organization with offices in Seattle and the nearby town of Kirkland, has a mission of fostering the spirit of compassion and humanitarian service in the world. When translated literally, “Tzu” means compassion, and “Chi” means relief.

In a room inside this King County building, Jordan Van Voast weekly sits with women caught in the criminal justice system.

Although Tzu Chi was founded by a Buddhist nun in Taiwan – Master Cheng Yen – the meditation on the breath taught involves no belief system, and thus is comfortable for people of any religious affiliation, as well as for agnostics and atheists.

I press the meditation timer app on my mobile phone, and a chime signals the start of the meditation. We begin by scanning the body and relaxing muscle tension. Then we turn our attention to the breath.

“Simply notice the moment- to-moment physical sensations of breathing, the in-breath, the out-breath, the space between the in-breath and out-breath,” I say. “Whenever a thought arises, no matter what it is, simply let it go and return to the breath, either focusing on the opening of your nostrils, or the rise and fall of the low abdomen.”

Any seasoned meditator knows that while the instructions are simple in theory, they can be difficult to accomplish in practice. Meditation requires an enormous amount of patience, persistence, self-forgiveness and courage, to endure the emotional storms of the mind.

The five-minute-interval chime sounds, and I open my eyes a little bit and scan the room, to see how everyone is doing.

Two of the women are curled forward against the table, faces buried in their crossed arms, apparently sleeping. One is leaning back in her chair, eyes closed and slightly rocking back and forth. The fourth person has her eyes open and appears to be searching for something in her pocket. The last person looks rock solid in meditation, spine straight, body still, breathing slow and steady.

In my nearly two years of volunteering in this program, my personal observations bear out the statistics: that people caught in the criminal justice system are disproportionately impoverished, people of color. Of the five women in the room, four are women of color.

At the 15- minute bell I invite everyone to open their eyes again, and ask if anyone would like to share her experience.

After a lengthy silence, the rock-solid meditator says how calm meditation makes her feel. After another pause, one of the other participants opens up and hints about the challenges in her life, and how difficult it is to calm the mind. The others nod their heads.

“This is as a sign of progress,” I say. “First we have to learn to observe our present state of mind, to stay focused even if what we see makes us a little uncomfortable.”

One woman talks about how her ADD (Attention Deficit Disorder) makes it difficult to focus. Some of them have had a cigarette break immediately before class. There are many challenges for these individuals – both internal and external.

During my two years at CCAP, I’ve observed many participants sincerely try to learn to meditate, while others seem more intent on ticking off an item on their case-management check list, and moving on as quickly as possible.

And why would they choose otherwise? Who would ever wish to be “corrected,” rather than encouraged and inspired by compassionate individuals?

To be corrected implies institutional force, and despite all the kind and well-intentioned people working with these women, there exists a larger reality of people caught up in the criminal justice system. It is noble to speak of liberation and enlightenment, but how are these people going to find meaningful and stable employment, decent housing, and educational opportunity? If anything needs correcting, it is the racism, poverty and socio-economic inequality in our world.

In some ways, I think teaching meditation to work-release offenders is more challenging than teaching to incarcerated prisoners. The latter have only the bland existence of life behind bars, so any class or structured activity brings a whiff of freedom (both worldly and spiritual), and thus generates a lot of spontaneous interest. But work-release offenders already are fully engaged with all the excitement, distractions and challenges of living in transition between worlds, and the subtlety of meditation can elude them.

Even with all the difficulties of kindling the flame of awakening in this population, remembering the principle of Buddha nature – that all sentient beings are innately good – reminds me of the precious opportunity that we have to help others going through difficult periods in their lives. There are no inherently evil people, only conditioned ignorance and negative habits that need to be patiently transcended (as opposed to the notion that criminals are bad people needing “correction”).

The juxtaposition of these Buddhist truths with modern criminal justice systems is the front line of practice for programs like CCAP. With budget cutbacks for social programs a perennial challenge, collaborations between government and non-profit volunteer like Tzu Chi are becoming increasingly common.

Even with all the shortcomings of working within an institution that is imperfect, the opportunity to help people move one step closer to liberation from inner slavery – the “prison of life” as one Thai master used to refer to worldly existence – is a gift.

I also feel a responsibility to give back what others, including my teachers, have freely shared with me. But for my white-skinned upper-middle-class Anglo-Saxon privilege, I might easily have landed in “the system,” resisting “correction” and searching desperately for a way out.

And then there are pleasant surprises like Dana – not her real name. She is the “rock-solid” meditator in the group. She told the group that recently she attended a 10-day vipassana course, which changed her life.

Who knows where people get the spark of inspiration that launches them on the spiritual path?

All I know is that my job is to keep planting the seeds, seeing the (non-sectarian) Buddha nature in each individual, and offering supportive spiritual friendship. Such friendship is the whole of the spiritual life, according to Buddha.

Photos by Steve Wilhelm