Salem, Oregon, Celebrates New Zen Sensei

Written by: Thomas Mattison

Lee Ann Nail, who has received formal transmission as an independent Zen teacher in the Harada Yasutani lineage.

After 28 years of Zen study, Lee Ann Nail received formal transmission from her teacher Roshi Ruben Habito on Dec. 8, 2012

The ceremony empowered Nail as an independent Zen teacher in the Harada Yasutani lineage. Her new teaching name is Kanren-An, which means “contemplating lotus hermitage.”

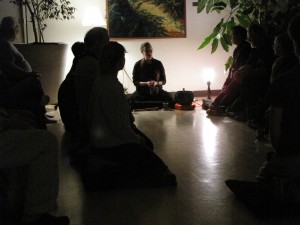

Lee Ann Nail during the transmission ceremony.

Sensei’s current intention is to continue her Zen study, and to teach locally in Salem, Ore.

Her sanghas (practice communities), the Unitarian Universalist Compassionate Mind Sangha and Salem Zen Center, now joyfully refer to her formally as Sensei An, in honor of this new role. The transmission means that Sensei An’s students can now study formally with her, and attend Dokusan.

Dokusan, a traditional Zen term, is an individual meeting that often occurs during zazen, when the sangha is meditating, and is held near the meditation site. The student performs three bows in arriving and departing the meeting. The opportunity to study with the teacher is seen as taking place within the middle of one of these bows.

“This ceremonial meeting is intended for the student to be aware, to be grateful not just for the opportunity to study together, but for the opportunity to encounter the dharma. It’s no small thing,” Sensei An said. “In American we don’t often notice all the fortuitous circumstances that bring us to a place at a particular time, when we are at the place in our life and have the leisure to be able to truly study, what is at the core of things.”

The entrance of the Salem Zen Center.

She added, “It’s vital to be grateful…grateful for the buildings and ground that are provided, for existing at a time of relative peace and for being well-nourished. We are often blind to these simple things. They are often taken for granted. Part of entering into formal study is bowing to this opportunity with gratitude – realizing that we are practicing then, on behalf of everyone, everything just as the Buddha did.”

Sensei, who is also a social worker, said a key to dharma practice is embodied in the term “praxis,” where insight becomes embodied in daily life.

When asked to further clarify what exactly was transmitted in the transmission ceremony, she said that there is “no thing” to be passed on – that the point of Zen is to wake up to the reality under one’s nose, each moment all along.

Lee Ann Nail teaching at the Salem Zen Center.

Her favorite example of this is found in Zen Master Dogen’s “Genjo Koan,” the koan of everyday life and its emphasis on practice/actualization. In brief the koan says:

“to study the way is to study the self, to study the self is to forget the self, to forget the self is to be enlightened by the 10,000 things, and that this practice/realization continues endlessly.”

In Zen communities it is vital for students to take on formal service roles, to help support and sustain healthy practice centers and also as an opportunity to explore the Genjo Koan itself, Sensei said. To this end, she has served as founding president for the Maria Kannon Zen Center, on the board of the Dallas Zen Center, as development director for Zen Mountain Monastery, and tenzo (head cook) and founding editor for the Zen Community of Oregon’s newsletter.

Tea ceremony at the Salem Zen Center.

Sensei’s formal studies began with Roshi John Daido Loori of Zen Mountain Monastery, including several periods of extended residency from 1985 through 2007. Her training included concurrent study with Roshi Habito, from 1989 though1994 and 2007 through 2013.

Now, as a Zen teacher, Sensei presents annually at the International Lay Buddhist Forum on the persistent issues of dual relationships within the American Zen Buddhist community. Over the years she has attended approximately 150 weeklong sesshins. Under the guidance of her own teachers, she has also studied with Jan Chozen Bays Roshi, Leonard Marcel Roshi, Shodo Harada Roshi, and at the Zen Center of New York City.

The Salem Zen Center sangha in meditation.

While in Zen the term transmission has many meanings and is an empowerment to teach, Sensei said that actually transmission is just Genjo Koan – it’s only as helpful as the meal of the day. She said then it’s important to wash the dishes, take out the trash and tend the garden.

Her favorite story along these lines is of Zen Master Joshu, who refused to teach even after having completed his formal studies, and who at 80 years of age set out on a pilgrimage for 20 more years of study. Master Joshu apparently then returned to his temple, and taught until he was 120.

Sensei said it’s this kind of attitude that will keep Zen alive in the U.S., “the willingness to always begin again.”