In India, Seattle Lama Presents on Links Between

African Americans’ and Untouchables’ Experience

Written by: Sharyn Skeeter

Martin Luther King III, Congress Vice President Rahul Gandhi, Nobel Laureate Kailash Satyarthi, Karnataka Chief Minister Siddaramaiah and others, during the inauguration of the Dr B R Ambedkar International Conference 2017.

Photos by – Ambedkar Foundation, Government of India, PTI/Shailendra Bhojak, Rainbowdharma international

Lama Choyin Rangdrol, a Seattle-based African American lama of Tibetan Buddhism, traveled to India in July as an invited presenter to the B.R. Ambedkar International Conference in Bangalore, India.

Dr. Bhimrao Ambedkar, an important figure in India’s history in many ways, is best known among Buddhists for his mass conversion of hundreds of thousands of Indian people to Buddhism. Ambedkar died in 1956.

Lama Rangdrol teaching at Triratna Bauddha Mahasangha Bauddha Vihar, Poona, India. This is the city where the 1932 Poona Pact was negotiated by Ambedkar, to end Mahatma Gandhi’s famous fast.

Lama Rangdrol said participating in the conference was very powerful, because he saw so many parallels between the experience of African Americans and Indian people who fall outside the caste system, who traditionally were called untouchables.

Also known as Dalits (broken or scattered people), these people of India increasingly prefer to be called Bahujan—meaning “people in the majority.”

“I’m a changed person. It changed me because I saw the passion and the compassion of the entire Earth coming to find out what’s going on,” Lama Rangdrol said of the conference experience. “It was a deep experience to witness the grand politic of India vie over who will address the tremendous suffering of caste, and how.”

The July 21-23 conference’s theme was a “Quest for equity—reclaiming social justice, revisiting Ambedkar.” Over 9,000 participants—academics, activists, policy-makers, and others—attended from around the world. Indian dignitaries included Indian Congress Party Vice President Rahul Gandhi, great grandson of India’s first Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru.

Martin Luther King III, global humanitarian; Rahul Gandhi, member of Indian parliament; pay homage to Ambedkar.

The conference covered protecting rights of Bahujans. as well as political representation, social justice, human development, governance and labor issues.

Lama Rangdrol is a Seattle-based teacher in the Whispered Lineage of Tibetan Buddhism’s Nyingma school. His teacher was H.E. Khempo Yurmed Tinly Rinpoche. Conference organizers invited Lama Rangdrol because as an African American, he can uniquely interpret Ambedkar’s comparisons of untouchability, American slavery, Jim Crow and Buddhism, in the context of social justice movements.

Lama Rangdrol has studied and worked with African-American Buddhists communities in the U.S., and with the Bahujan Buddhist community in India. He wrote the book “Black Buddha: Changing the Face of American Buddhism,” featured as a classic in American Buddhism (Buddhadharma Magazine, Summer 2005). He teaches by invitation in the Northwest and elsewhere.

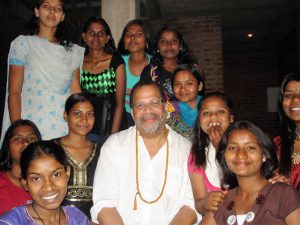

Lama Rangdrol with Bahujan children, sometimes known as untouchables or Dalits in caste terms, during an earlier visit to support these people.

Bahujan issues are, of course, similar to those of African Americans. But Lama Rangdrol, who has offered Buddhist teachings at Seattle University and at Nalanda West in Seattle, sees a difference when he goes to India.

“When I teach in the slums I see little Buddhist wheels on the doors of dilapidated shanties,” he said. “Honestly, I felt I never understood Buddhism until I saw that, because Bahujans in a hopeless situation reach for beliefs to sustain them in conditions of human degradation incomprehensible to the Western mind. Our Western Buddhist centers, and high-minded approaches to socially-just meditative equipoise, are of no use to them.”

Bahujan people became Buddhist, he said, as “a tactical means of throwing off casteism’s psycho-spiritual torment, while they remain immersed in never-ending dehumanization.”

On the other hand, Lama Rangdrol said, “When Ambedkar’s Buddhist social justice model migrates to African-American consciousness, the Buddhism throws them off. The more they hear about Buddhism the more they migrate back to faiths that have no origin in African America, other than enslavement of the African mind in America.”

Lama Rangdrol surrounded by Bahujan Buddhist women, also during an earlier visit.

Lama Rangdrol calls this the “Icarus conundrum.”

“At the conference, I specifically addressed how comparative analysis of untouchability and slavery conditions led Dr. Ambedkar to convert to Buddhism,” Lama Rangdrol said. “Conversion away from religions used to justify enslavement of Africans is a very foreign tactical decision to African-American culture. It doesn’t translate because the African-American social justice movement is deeply rooted in the Christian idiom of their enslaved American ancestors.”

He said that in the United States “We get into our Americanisms and our ethnicisms and we ism ourselves out of what we are really—the light of the world and nothing else. We lose track of that. That’s something that we really have to take to our meditation and never forget.”

Ambedkar, an Indian change agent

Dr. Bhimrao Ambedkar (1891-1956) was an economist and lawyer. He is considered the man who almost singlehandedly drafted India’s constitution. This is remarkable because Ambedkar was born into the caste formerly known as untouchables, people who continue to suffer social injustice and disparity, according to the Robert F. Kennedy Center for Justice and Human Rights.

Dr. Ambedkar taking Buddhist deeksha (ordination), before leading the same ceremony for 300,000 Bahujan on Oct.15, 1956, in Nagpur, India. His wife, Dr. Savita Ambedkar, is at his side.

Ambedkar was born a Bahujan Hindu. Through strength of character and intellect he graduated from high school with distinction, which was rare for a Bahujan of his time. He received grants to study abroad, and earned master and doctorate-level degrees, and a law degree, at New York’s Columbia University and universities in England.

When Ambedkar returned to India he became involved with politics. After Indian independence from Great Britain in 1947, he was appointed India’s first law minister and became chair of the committee to draft India’s first constitution. India’s caste system, based on the dominant Hindu religion, presented issues for the writers of the young republic’s constitution. Ambedkar based India’s constitution on the U.S. constitution, including secular separation of religion and state.

Ambedkar continued to fight for Bahujans’ human dignity, political representation, and right to self-defense, as well as for the empowerment of women.

In 1935 Ambedkar publicly signaled interest in changing his religious faith, declaring that while he was born into a religion that perpetuated caste injustice, he would not die in one. After 20 years of research and comparison Ambedkar decided to convert to Buddhism, because it was indigenous to India. In addition if other Bahujan people converted, Buddhism would give them a religion free from caste.

Dr.Ambedkar in a group photograph with female Buddhist activists.

Ambedkar took his Buddhist deeksha (ordination) on October 15, 1956, in Nagpur, a large city in the central Indian state of Maharashtra.

At that ceremony, 300,000 Bahujan people converted to Buddhism with him. During a press conference on the eve of his deeksha, he was asked whether he would follow the Theravada or Mahayana tradition. He said, “I will do Navayana. ‘Nava’ means ‘new.’ So I’ll do a new yana.” With that, he avoided the controversy of choosing one tradition over another.

Ambedkar was influenced by, but not directly involved in, the African-American Harlem Renaissance movement while he was attending Columbia University, according to Harvard University Bahujan scholar Dr. Suraj Yende. Columbia is adjacent to Harlem.

Scholars see many parallels between Ambedkar’s inspired work and the African-American civil rights movement. Some of these scholars include Yende, African-American law professor Dr. Kevin Brown of the University of Indiana, Lama Rangdrol, and Prakash Ambedkar, Dr. Ambedkar’s grandson.

Ambedkar’s social critique of Bahujans, and African Americans, had the goal of liberating those groups from oppression associated with elements of their respective majority cultures.

Ambedkar conference organizers, such as Bengaluru Central University professor Dr. S. Japhet, understood this when they invited Martin Luther King III and Dr. Cornel West to participate in the event, even though West was unable to attend.

Lama Rangdrol said of his experience in India with Bahujan people, “Sometimes Westerners go to India and see all the suffering. They really don’t know what to do with it. They just observe it and it’s really overwhelming. My practice is to enter it. My meditation is to survive the intense experience. It is not easy. All I know is to rest on Ambedkar’s wings, the moral teachings of Buddha, and love.”