For the First Time, Washington Prison Inmates

To Teach Mindfulness to Others Behind Bars

Written by: Tenzin Gache

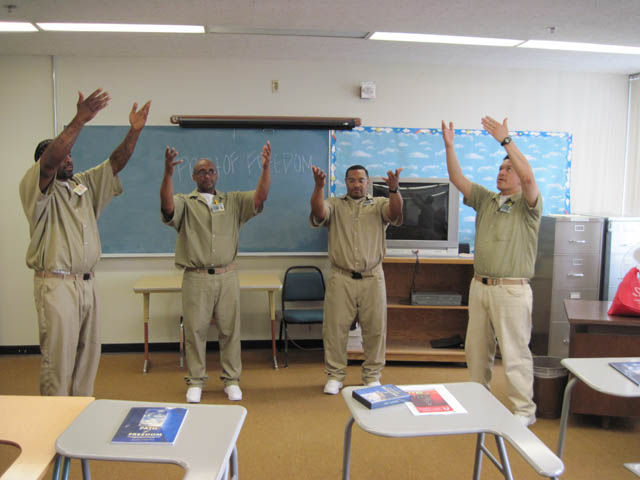

Nate, second from right, leads a mindful movement exercise, a component of every class.

Photos by: Terry, an inmate at Washington Correction Center in Shelton, Washington.

Four Washington state prison inmates are making history by becoming the first inmates certified to teach Path of Freedom, an emotional intelligence program based on mindfulness meditation.

As certified trainers the four are starting to teach the 12-week curriculum to other men behind bars. The Path of Freedom program was developed by the Massachusetts-based Prison Mindfulness Institute.

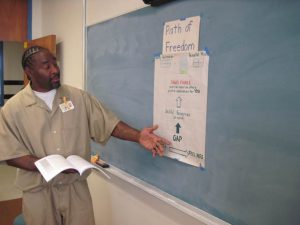

Ji explains how mindfulness and meditation practices help us to work more skillfully with our thoughts and feelings, to create the “gap” from which genuine choice arises.

These enthusiastic and dedicated men are venturing into uncharted territory.

Path of Freedom has been taken into prisons across the U.S. and Europe for many years, but only by outside volunteers who pay for and complete a six-week online training course.

This initiative is important because prisoner-facilitated classes have the potential for “growing” the program and getting it to a greater number of people behind bars, both men and women. Outside volunteers often encounter a variety of time constraints that conflict with the needed 12 weeks of consecutive attendance. Other factors like inclement weather can also result in the cancellation of volunteer-facilitated classes.

By contrast, prison inmates have the time. They have experienced the benefits that program offers to the incarcerated, and thus are confident about what they teach. They are energized by a deep wish that more men behind bars have access to this knowledge.

Ji, facilitator-in-training and a mural artist, greets Ven. Gache in the foyer of the education building.

The men consistently demonstrate enthusiasm for the skills they learn. One Sunday during a closing circle, prisoner Max said, “I’m giving up soccer to come to this class, and I really, really, really love soccer!”

The transition to teaching men to teach each other wasn’t an easy one, arising from a conversation between myself and colleague Sue, during a cold and slippery walk at a Washington state prison. We were leaving our shifts as meditation trainers at the Washington Corrections Center, a maximum security prison in Shelton, Washington, south of Seattle.

Sue and I began asking each other, “Why aren’t the men facilitating this program? How might they get access to the training videos?”

We popped this question to Kate Crisp, the executive director of Prison Mindfulness Institute.

“No one has ever asked that before. Let me think about it and get back to you,” was her emailed response. A few days later we were cleared to try out this idea, and asked to provide weekly feedback to the institute.

Sequoia, on the right, leads a meditation at the beginning of class.

But first we had to get buy-in from the prison. Over the next several months Greg Garringer, the very supportive chaplain, secured approval from his supervisors.

In the spring Prison Mindfulness Institute sent facilitator training DVDs to the chaplain. The DVDs were crucial, because lack of internet access has excluded incarcerated men and women from enrolling in this training.

In July we began the training the four men who had volunteered to undertake the challenge to become teachers.

At the start of our first class inmate Nate pointed out how helpful it would be present the program to R-4s and R-5s, men who stay at the prison for only six weeks before departing for other prisons. During their time at the Shelton facility no day programs are available to them.

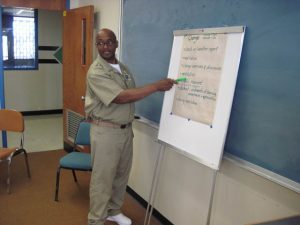

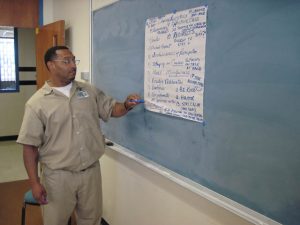

Stephen goes over the agenda at the beginning of class.

“They just sit around and watch T.V.,” said Chaplain Garringer, “ I wish there was a program for them.”

But change comes slowly in the prison system. I myself was initially rejected in 2015, when I first asked to teach the Path of Freedom only months after first volunteering.

“No,” Garringer said, “ you don’t have enough experience under your belt. I can’t allow you to come in alone.“

I had to “do time” with other volunteers, or never go in alone. During the subsequent monthly walks in and out of the prison for the Buddhist meditation group, Sue and long-time volunteer Jeff Miles got to hear all about my failed attempts to get the Path of Freedom program into three correctional facilities.

Over many months Sue and I repeatedly entered through prison security and picked up our volunteer “red badges.” We then walked through the automated, locked doors of the administration building, passing into the inner courtyards of the prison itself.

Sequoia practices facilitating a brainstorming session, to establish a set of agreed-upon class rules.

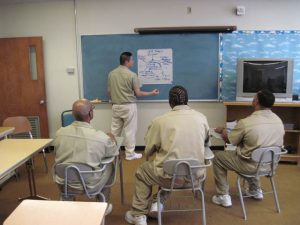

When we arrived at the second-floor classroom of the education building, we arranged the room and waited for the men to join us.

Voices would be heard, men giving their last names and prisoner numbers to the correctional officer seated behind a counter at the top of the stairs. A few minutes later, four men in khaki-colored, short-sleeved shirts and trousers, would file through the classroom door.

Smiles would flash, greetings would be exchanged, and a sense of comfort and ease would settle over the room, nurtured by the many hours we had spent together. From January to April these four men learning to be teachers, along with 10 others who were in the class itself, participated in the weekly Path of Freedom class.

The men training to be teachers prepared for each class by reading about the upcoming topic in their Path of Freedom workbook. They completed and turned in homework that included a quiz, a daily meditation log with their personal reflections, and a weekly contemplation in which many shared written insights.

In his log Jason wrote, “I really never knew much about meditation before. Now I’ve found it to be very useful.”

In his log Jason wrote, “I really never knew much about meditation before. Now I’ve found it to be very useful.”

Stephen wrote, “I am much more mindful of my thoughts now and that helps me make better choices.”

On the end-of-course feedback form, Bill wrote, “I found out so much about how to control my negative emotions and find peace in my own mind.”

During each class the men shared how they had applied the prior week’s tools and strategies.

Danny reported, “This week in the kitchen where I work, two men started shouting at each other. I usually get very anxious when that happens. I noticed my heart start to race. I was able to take deep breaths and calm myself.”

As the class progressed, Sue and I began to invite the four trainees to join with us in facilitating the class. They began leading the meditations at the beginning and end of each class; then they offered to lead the mindful movement component of each class.

Each week the men demonstrated their commitment to positive change in their lives. They were doing the work to progress along “the path of freedom,” the path away from emotional reactivity. Visitors would comment on the compassion, engagement and intellect of our group.

“Men need this class the very first week they enter this prison,” said Nate. “These skills can help reduce their suffering while they’re in prison. They can cultivate new habits while they’re behind these bars, which will serve them here as well as when they get out.”

It is possible that Nate and Chaplain Garringer might have their wishes fulfilled.

Through this program I hope to help fulfill one of the wishes of His Holiness the Dalai Lama: that all people—no matter what religious persuasion or no religious persuasion—are supported in discovering ways to eliminate destructive emotions from their lives. Through this may they reduce their suffering and gain greater happiness, the birthright of all human beings on this planet.