What’s New and What’s Ancient With Your Mala?

Written by: Valerie Grigg Devis

People wearing malas celebrate a “Listening to the Sound of Silence” retreat at the Trappist Abbey in Carlton, Oregon. The retreat was taught by Jerry Braza from the Order of InterBeing.

Photos by: Jean-Luc Devis, Valerie Grigg Devis, Greg Eisen, Jessica Morgan , Sustainability Project, Yowandu Tibetan Travel, Steve Wilhelm

Around the Northwest, Buddhist practitioners are using the strings of beads called malas in new and sometimes-surprising ways. And maybe not so surprising, here in 2020, some people are adapting digital devices to support their dharma practice as effectively as physical malas have since the time of the Buddha.

As I reached out to Buddhist practitioners around the region, I was fascinated by the array of perspectives they bring to their mala use.

Malas sold in Seattle empowering refugee Tibetan nuns in India

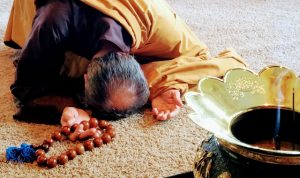

Jisen Seido, a student of Koro Kaisan Miles in Olympia, Washington, practices bowing while using a large set of mala beads.

Seattle-based Tibetan Nun Project in 1987 began raising funds to educate and empower nuns in the Tibetan tradition as teachers and leaders. Today their work supports over 700 nuns in eight nunneries in India and Nepal, part of this by selling nun-made malas online.

Executive Director Lisa Farmer spoke from her Seattle office about recent mala trends.

“We are selling more internationally, thanks to our growing online presence and social media,” she said. “People are looking for gifts that are ‘meaningfully made’ and ‘ethically sourced’.”

Tibetan Nuns Project has become a “major source” for malas from the Pacific Northwest, Farmer said. Best sellers include malas made of carved sandalwood beads, while rose quartz and coral beads are also popular choices.

Other popular Tibetan Nuns Project items include Tibetan prayer flags and kataks (prayer scarfs).

When digital counting replaces clicking beads

Volunteers at Tibetan Nuns Project sometimes pack malas made by Tibetan nuns in India, for online sale from Seattle. From left Deb Slivinsky, Shu-Hsiang Wang, Erika Bartlett, Iris Antman.

Numerous apps offer the same functions as traditional malas, especially for tech-savvy Northwesterners who also practice the dharma. Is it time to toss your mala beads?

Members of some sanghas consider technology a useful tool, while others remain suspicious of innovation. Is there a middle path?

Perhaps you use an app that times your daily meditation with a lovely bell at the beginning and end. This frees you from clock-watching, or following the breath with physical beads.

We know of one particularly creative Northwest practitioner who devised a counter for his bicycle, so he could count mantras while riding. He also envisioned his bicycle wheels as prayer wheels increasing merit as they turned.

But for those more aligned with traditional malas, here are some of the ways dharma leaders around the region instruct in mala use.

A Vietnamese Zen perspective

Soapnut tree nuts were used to make the first malas mentioned in the Pali Canon, the original texts of early Buddhism. Soapnuts are about the size of a nickel.

When I contacted Jerry Braza, facilitator of the River Sangha in Salem, Oregon, he mentioned he was ordering a couple of hundred malas from Catholic nuns in Vietnam.

“Really? For what purpose?” I asked him. Braza’s group practices in the Zen tradition of Thich Nhat Hanh

“I met the nuns when visiting Vietnam with Thay (Thich Nhat Hanh), on his first trip back to Viet Nam after 40 years,” Braza said. “I have always been intrigued with malas from a practice standpoint and the value they have as a symbol. Twenty-some years ago I stopped wearing a watch and replaced it with a mala, and have worn one ever since.”

Braza continues to purchase malas from these Catholic nuns.

“I give the malas to anyone who says, ‘I like your bracelet,’” he said. “I just ask ‘Would you like one?’ and give them a mala from my wrist. Now I meet people who ask if I have any more malas, since theirs broke. Another mala gift opportunity!”

Braza uses his mala as a device when meditating, “…whether focusing on simply the breath or on the guided meditation or both. It helps keep mindfulness alive.”

A Japanese Zen perspective

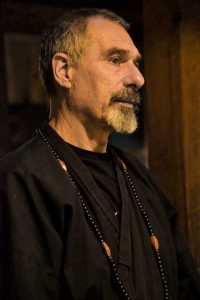

Jean-Luc Devis wears a beautiful mala given him by his wife Valerie Grigg Devis, following his taking-refuge ceremony at the Salem Zen Center.

Roshi Lee Anne Nail, teacher at the Salem Zen Center in Oregon, expresses her experience with malas as an evolving one.

“I used to understand malas as a way to connect to breath, to count breath or in many traditions to count mantras or bows,” Nail said.

“Then, one winter during monastery training, I tuned into the sound my teacher’s mala made. The zendo would get really quiet, and I noticed that every once in a while, my teacher would move his mala and make a clicking sound. Occasionally the head monk did the same. This made me wonder: ‘Were they making a sound on purpose? Did it have a meaning? Was it a reminder of the importance of breath? Or a way to let go?’

“That winter this sound became so intimate that tears would come to my eyes each time it occurred. I had no idea why,” Nail continued. “At some point this tiny sound was no longer ‘outside’ of me. Yet, I resist defining it. This tiny sound points the way home. Can you hear it?”

A Korean Zen perspective

Zen Master Jeong Ji (Anita Feng) demonstrates mala use at the Blue Heron Zendo in Seattle.

Roshi Anita Feng, teacher of the Blue Heron Zen Center in Seattle, explained her Korean Zen mala use.

“There is a history of using malas in the Korean Zen tradition. Our root teacher, Zen Master Seung Sahn, practiced with a mala,” she said. “Practicing with a mala is both a focusing and an ‘accounting’ technique. They are not separate. Combining body, breath and mind, we account for our whereabouts as the thumb and forefinger pass from one bead to another.

“Just as when we do walking meditation and we focus on each part of the sole of our foot meeting the floor, so too with fingering the beads of the mala. Some of us use a mala to register the completion of each internal recitation of the Great Dharani. Others use it to register a single breath. Some find that simply wearing a mala reminds them to stay present in the midst of daily life.”

A Chinese Zen perspective

Koro Kaizan Miles, founder of Open Gate Zendo in Olympia, which is in the Chinese Linji Zen tradition, said he uses his malas in three ways.

“First, when I am suffering physical pain or stress, I use my mala to slow down and regulate my breath,” he said. “Within a few measured breaths, my breathing slows from about 30 per minute to around 18 per minute. I usually continue until it is stable at about 12 breaths per minute. This produces a much calmer effect.

“Second, when I do my 108-bow practice, I use the mala to count bows. I typically use my wrist mala because it is easier to hold while bowing. Since my wrist mala has 27 beads, I bow 27 times, then do nine rounds of kinhin (walking meditation), then repeat bowing until I have bowed 108 times.

“I do this as a form of calisthenic exercise, as well as a meditation,” Miles said. “Doing this regularly helps me to maintain my ability to bow during ceremonies.”

“Third, I have a mala looped over the stick shift of my truck. I often use it to relax when I am stuck in Seattle traffic. This makes the most productive use of my time!”

A Tibetan Buddhist perspective

Bins of malas from India, ready to be sent around the world to help fund nuns supported by Tibetan Nuns Project in Seattle.

“It’s a counter,” said Thubten Chonyi, about her mala. Chonyi is a nun at Sravasti Abbey, a Tibetan monastery for Westerners near Newport, Washington.

Chonyi explained that traditional Tibetan malas function as a sort of “abacus,” an ancient counting device. Tibetan malas utilize two tassels, each with 10 small beads attached, to track the completion of 100, 1,000 and up to 100,000 mantras around the 108-bead mala.

Sravasti supporters are using their malas to count a million mantras, as part of raising awareness and positive energy for the abbey’s planed new Buddha Hall. Their website is currently collecting mantras, and you can listen to a recording of the mantra, recite it as many times as you like, and then submit a form adding your recitations to the other mantras collected so far. The total number is visually recorded on an electronic mala online.

“Mantras are like the utterances of a holy being in deep meditation,” Chonyi said. “We see this as a way to make a connection with the deity.”

Mantras are also considered a form of “mind protection” and a powerful expression of commitment to practice, she said.

“We believe that if you continue to recite a mantra like om mani padme hum you will develop compassion,” she said. “Whether you want to or not!”

How mala use began

Tibetan Buddhist malas are the “abacus” of prayer beads. Each side tassel includes 10 extra beads, to help user count accumulations of mantra repetitions.

The origin of Buddhist malas (Sanskrit:”garland“) is attributed to the “Mokugenji Sutra,” in which King Virudhaka asks the Buddha to help ease his suffering. The Buddha recommends that he recite “the three refuges” using a mala made of the seeds of a soapnut tree.

Since then malas have been made of simple, organic materials, such as wood, stone or bone. More lavish materials such as gems are not used, because the mala is a meditation tool, not a piece of jewelry.

Buddhist monks are prohibited from wearing jewelry and serious lay practitioners also follow this example. The recent popularity of malas has created a wider variety of options, including colorful polished stone beads.

Valerie Grigg Devis is a recovering bureaucrat, with 30 years of state and local government experience and a master’s degree in urban and regional planning. Since retiring she is a Buddhist minister in training, a serious gardener and a visual artist. She has discovered an invisible mala she can use when she forgets to wear one: Just touching her thumb to each of her fingers on the same hand. (Repeat!) Devis lives in Corvallis, Oregon, with two rambunctious cats and a French husband who likes to cook. She can be reached at griggdevis@gmail.com