Poetry Deepens Dharma for Port Townsend Sangha

Written by: Ellen Ostern and John Wrobleski

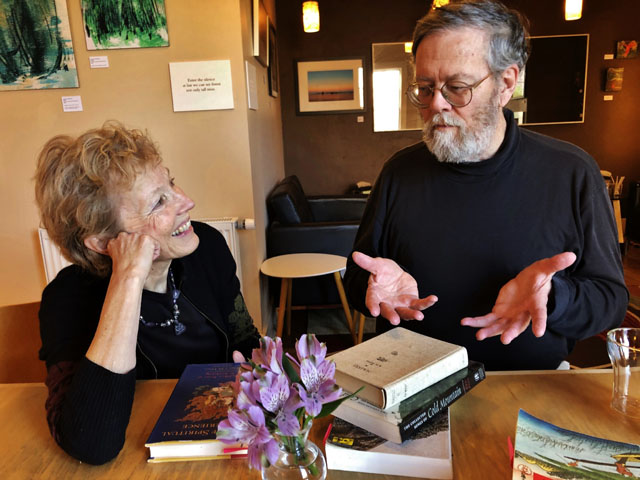

Port Townsend Sangha members Ellen Ostern and Karma Tenzing Wangchuk discuss poems in a teahouse where Tenzing likes to read.

Photos by – Steven Mullensky, Karma Tenzing Wangchuk, John Wrobleski

“A rose is a rose is a rose.” Well, maybe not always!

When Port Townsend Sangha member Karma Tenzing Wangchuk leads a dharma discussion, he provides poems that illuminate a topic.

Recently non-harming, impermanence, generosity and equanimity have been topics. We have then shone the light of our own experiences and understandings on those topics, often coming up with surprising and useful insights to share with each other.

Karma Tenzing Wangchuk allows the words to settle while his tea steeps.

A recent example on the topic of equanimity was this poem by Japanese priest Kobayashi Issa, who lived from 1763 to 1827:

New Year’s Day–

Everything is in blossom!

I feel about average.

(This was translated by Robert Hass in “The Essential Haiku: Versions of Basho, Buson and Issa,” 1995.)

One sangha member said he recognized profound wisdom in the poet’s ability to capture the essence of a spiritual truth in a simple description. Another person appreciated the image of a world in full blossom, acknowledging a sense of clinging and wanting to continue in that state, which led to an epiphany that “This is what leads to personal suffering.”

Others wondered whether feeling “about average” and being “equanimous” are equivalent states. Was the poet truly equanimous or was he indifferent to the beauty around him or even depressed? Someone asked rhetorically if there was room for joy, pleasure or contentment in equanimity.

Sangha members John Ricca, Andi Salmi and Michael Kasten follow along with Tenzing’s written handouts of poems.

And so it has gone, each week when Wangchuk facilitates a poetry dharma discussion.

The Port Townsend Sangha began 20 years ago in the founders’ home, in the maritime town of Port Townsend, Washington. As it grew the sangha moved several times, for the last four years meeting every Wednesday at the Port Townsend Friends (Quakers) Meeting House.

Because the sangha has no teacher, the sangha depends on individual members to sign up to facilitate the weekly dharma discussions. Most members stream a teacher presentation from websites such as Dharmaseed or Audiodharma.

Recently poetry dharma has sparked a different look at the teachings led by Wangchuk, who began attending Wednesday night meetings about a year ago.

Wangchuk is a published poet, scholar, book editor and former journalist, and a long-time practitioner of Tibetan Buddhism. In the mid-‘90s he began devoting more time to poetry, especially haiku and tanka, both Japanese poetry forms.

“They’re part of my bones now,” he said.

Karma Tenzing Wangchuk reviews the poems he will present for discussion at a weekly Sangha meeting in the sanctuary of the Quaker Meetinghouse.

Wangchuk’s training in the dharma is broad. He studied Buddhism with Zen mentors including Dr. G. Ray Jordan of San Diego State University, while continuing mahayana and vajrayana practices. Now he’s enjoying the opportunity to participate in a peer-led sangha with vipassana roots.

“There’s no classroom, no teacher, no students,” he said. “But I will say that I learn a lot along the way.”

Describing his process Wangchuk said, “Sometimes the shortest poems—a haiku, for instance—are best because they leave more unsaid than longer ones….Maybe we have to work a little harder, too. Not everything is spelled out for us. We can’t just sit back and listen passively.”

On the weeks when he facilitates the dharma discussion, Wangchuk selects topics fundamental to Buddhism, or that tie into previous sangha discussions. He then considers 20 or more poetry books and searches for appropriate poems on the theme.

He chooses a handful of short poems that express different views on the subject, some even contradictory at first glance. He looks for poems both inside and outside the Buddhadharma, including some that are “scriptural,” for example gathas from the “Dhammapada,” or verses from Shantideva’s “Bodhicaryavatara.”

Sangha members Shannon Rapauno, Peter Guerrero and Mike McClean share ideas during the socialization time between meditation and the Dharma presentation.

This provides a familiar hitching post for more secular poems by authors who might well not be Buddhist, like excerpts from Walt Whitman’s “Leaves of Grass” or Emily Dickinson’s “The Soul Selects Her Own Society” from her collection “Poems.”

“I like to mix things up,” Wangchuk said.

For instance he chose these stanzas on equanimity, from Walt Whitman’s “Song of Myself.”

I exist as I am, that is enough,

If no other in the world be aware I sit content,

And if each and all be aware I sit content.

One world is aware and by far the largest to me, and that is myself, And whether I come to my own to-day or in ten thousand or ten million years, can cheerfully take it now, or with equal cheerfulness I can wait.

(”Leaves of Grass,” 1892)

“The aim is to increase knowledge and support practice,” Wangchuk said. “To do it together and to have some fun.”

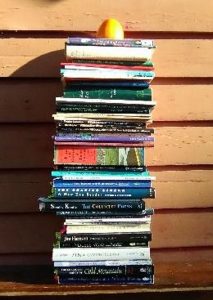

A stack of poetry books outside Tenzing’s home, which he will explore for poems on Dharma themes. A persimmon rests on top.

He often provides two or three-page handouts of the poems for reading along and for reflection. We can attest that his approach has stimulated thoughtful reflection and analysis, as well as an interest in investigating poetic expressions of the Dharma.

Wangchuk reads a poem and we sit with it in brief silence. Then, as it feels timely, others also read the poem aloud. As the poems are read with different inflections, pace and pauses, they offer more than we realized upon first hearing.

Poetry, especially haiku, “has been a kind of practice for me,” Wangchuk said.

“It isn’t that ‘haiku is Zen,’ but haiku can be a way of life, and haiku and Buddhism are often a good fit,” he said. “So it’s pretty natural for me as a poet and Buddhist to think that in a peer-led sangha like ours, we could make good use of somebody giving presentations on ‘dharma through poetry.”

He added that it’s not teaching dharma through poetry, “But more a matter of selecting poems and offering them for the sake of discussion. It is a teaching for me, though, this process. I get processed myself!”

Karma Tenzing Wangchuk responds to comments from Sangha member Pam Bartlett at the conclusion of his poetry facilitation.

Wangchuk moved to Port Townsend in 2006, partly drawn by the presence of many poets and several translators of Japanese and Chinese poets, and also partly due to the area’s robust anti-war activity.

Wangchuk is a Vietnam-era war veteran, and has participated in engaged Buddhism with civil resistance at local ports and with the Occupy Movement. He is an advocate for people who are homeless or living in the local homeless shelter, where he previously spent two years himself. He has served as a resident monitor there and today still serves on the shelter’s advisory council.

Wangchuk has written several poetry chapbooks including “Shelter\Street: Haiku & Senryu,” which won a Haiku Society of America award as best haiku book for 2011. His poems have appeared in such publications as “Turning Wheel,” “Inquiring Mind,” and “Dharma Drum,” and in anthologies including A Vast Sky: An Anthology of Contemporary World Haiku (2015) and Haiku in English: The First Hundred Years (2015).

The foyer at The Quaker Meetinghouse offers welcome posters and brochures, on a Wednesday night gathering of the Port Townsend Sangha.

It is precisely this combination of Wangchuk’s achievements, life experiences, and study of Buddhism, along with his curiosity and interest in creative expression with language, which has generated sangha enthusiasm for exploring poetic perspectives of the dharma. Our latest discussions have enriched our community by breaking our standard mold for presenting the dharma, and opening us to a shared experience over time and place of poets’ efforts to capture the essence of the dharma.

Port Townsend Sangha’s space sharing with the Friends Meetinghouse works well, because the two groups share similar values of silence, simplicity, peace and non-violence. More than 200 people receive the weekly meeting notice, with links to the upcoming dharma talk. Between 18 and 25 gather to meditate each week and discuss the dharma.

Ellen Ostern and John Wrobleski are long-time members of Port Townsend Sangha, and active volunteers.