Three NW African-American Buddhist Teachers

Share Their Perspectives (On the Way Things Are)

Written by: Genevieve Hicks

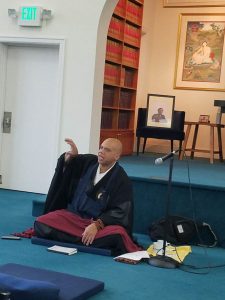

Jaye Seiho Morris, a Seattle Zen priest, taps his experience in his teachings.

Photos by: Genevieve Hicks, Fausto Villaneuvo

It is with the utmost delight that I present small snippets of conversations I had with three African-American Buddhist teachers in the Pacific Northwest.

These started out as interviews and evolved into heartfelt exchanges on topics near and dear to my heart. I am convinced that Buddhism has much to offer us Americans of African descent. Some of our particular brand of suffering is birthed of racial stress, and other visible and invisible oppressive forces, encountered while navigating the dominant culture of North America. Unfortunately many of our Western Buddhist Pacific Northwest sanghas are sometimes microcosms of this dominant culture. In these sacred spaces we find ourselves pushing into racial stress once again.

My own experience with these early labor pains in my own sangha propelled me to seek out Black Buddhist teachers for support and wisdom on the path. I spoke with these three teachers and please know we are lucky enough to have several other teachers of African descent in our region. The following words are a small thread of the cords that were touched on, during our long conversations.

Morris teaching at Nalanda in Seattle.

Jaye Seiho Morris found Buddhism at the library when he was 19 and high as a kite.

He was reaching for another book and instead grabbed Dogen’s “Chobogenzo,” often called a primer of Soto Zen.

The opening lines of the book smacked him sober. He recites it to me from memory:

“To study the way is to study the self. To study the self is to forget the self. To forget the self is to be enlightened by all living beings. To be enlightened by all living beings is to drop the barrier between oneself and other.”

The Japanese names of Morris’ Buddhist teachers flow off his lips in a way that makes it seem like he is speaking another language. I can’t keep up with the names of teachers nor the details of his lineage as he excitedly shows me around Chobo-Ji, Seattle’s Rinzai Zen temple where he lives and teaches.

Morris is a black Zen Buddhist priest (like Reverend Angel Kyodo Williams). He talks about being a yellow-skinned, blue-eyed black man, and about the suffering of being born into this particular sack of skin and bones. He did not belong to the white or black world, and when he found Zen Buddhism he finally felt that he belonged.

Morris and Genevieve Hicks, author of this piece.

He shares a bit about how his family has been impacted by the violence of racism, which includes lynching and torture. He said, “There is no justice; you cannot rectify what they did to my family.”

He does not see how justice for African Americans can be achieved. He speaks openly about structural violence and about the oppressive system that Blacks live under in this country. It’s constructed to grind people down and keep them as wage slaves.

Morris is not very optimistic about social change. He says it ain’t gonna end, so how do we prevail inside of this reality?

This is where Buddhism can help. It gives you practices that help you develop the capacity to be a solid human being, as they say in the Black community. Buddhism teaches you how to navigate these wretched painful systems in an integrated way; to be in the system but not of the system, to develop what Morris calls respond-ability.

Morris posts his teachings daily on Facebook and Twitter. He is an author and a recovering addict, and also works for an addiction treatment center. He offers weekly Zen Buddhist teachings at Chobo-Ji Center on Seattle’s Beacon Hill, and is a mentor with Refuge Recovery.

Tuere Sala, a mother of two and former county prosecutor, shares her life in her teachings.

Tuere Sala was a devout Christian law student in Kansas City, Missouri, who had just failed the board exam, again.

She went to a bookstore after church looking for a book. She knew all about the suffering of poverty, racism, sexism and abuse, and wanted to learn about how to end suffering. The book “Mind Training and Cultivating Loving Kindness,” by the late Tibetan Buddhist master Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche, saved her life.

Sala read that book 50 times over the next decade while working as prosecuting attorney, and practiced with each of the 59 slogans every day. For years her meditation practice was just counting, and then she realized the practice was supposed to be counting the breath.

The dharma of the 59 slogans forced her to look closely at herself and her own behavior, including the repeated cycles of violence and sexual abuse that started with her father and were replicated with the violent men she chose.

The tipping point of her divorce pushed her to move back home to Seattle. She continued to meditate, and now looking back, notes that it was a constructed mental practice from the head up, very disassociated.

Sala at the Reverend Angel Kyodo Williams teachings in Seattle.

Her Seattle teacher Rodney Smith helped her to get back into the body, to experience the dharma from an embodied perspective. To arrive into an embodied meditative practice she had to go through the anxiety and trauma, and it took years.

This process of re-entering the body can happen during meditative practice, and at times it was very painful for Sala because it can involve re-experiencing trauma during meditation. She warns that secular mindfulness practices are not really preparing people for what can happen when you watch your breath.

Sala notes in retrospect that it was her absolute faith in the dharma, grounded in years of studied practice, which allowed her to sit through the levels of anxiety that came about in her embodied sitting practice. Now she thinks of herself as being unhooked from her traumatic past. And how does the dharma help with living in a world that is racist?

In the dharma you can totally accept that this is what is happening, she says, and at the exact same time have the courage to resist falling into the flow of it. Only an embodied dharma can allow you to do this.

Tuere Sala is one of the guiding teachers at Seattle Insight Meditation Society, and is founding teacher of Capitol Hill Meditation Group.

Teacher Larry Ward, in Mexico City.

Dr. Larry Ward was exposed to Buddhism as part of his responsibilities as a faculty member of the Ecumenical Institute.

Ward practiced for 20 years in different Buddhist traditions, before he began practicing with Thich Nhat Hanh in 1991. From the very beginning he found Buddhist practices helpful for managing the stress and chaos he experienced while serving the world, first as an ordained minister then as a dharma teacher.

Ward was involved in the civil rights movement, and notes that as a young spiritual practitioner the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. changed the trajectory of his life.

Now, as a senior dharma teacher in the tradition of Thich Nhat Hanh, Ward believes that Buddhism only has meaning if it is connected to a lived experience. Buddhist transmission to the West is in its infancy, he says. We in the West are just beginning to realize that meditation and dharma are more than just an emotional salve.

Many white Americans are trying to use the practice to be comfortable with deconstruction, and may not have a sense of how the practice can help us reconstruct, build a new society. They think of the practice as some kind of intellectual exercise and do not really understand the difference between healing and transformation.

If applied correctly, this practice has the potential to lead to a profound and embodied transformation. This is a personal transformation that must lead to a societal transformation.

Ward teaching in Seattle.

After working and traveling around the world with Thich Nhat Hanh, Ward has decided to develop his own approach to Buddhism, one that is relevant to the audiences he serves. His approach includes integrating techniques including trauma resiliency, Buddhist psychology, bodhisattva training, and shamanic training.

If you go deeper into this practice Ward says, you begin to touch the suffering of all beings along with your own suffering. There is absolutely no way you can do this practice and not want to help alleviate the suffering outside of yourself.

Ward implores Buddhist practitioners not to try and “get by” without losing anything. We can’t bypass the profound work we each need to do to investigate our own conditioning (including but not limited to race, gender, sexuality, class, religion and national origin).

Allowing for profound embodied transformation means taking risks. And what are we risking? Our life force.

Ward says we must be willing to risk our life force, to risk allowing ourselves to be deconstructed and then reconstructed. We must risk putting our life force into service, including the service of having our consciousness transformed. It is only through transformed consciousnesses that new societies can be built.

You can find Dr. Larry Ward’s teaching schedule at the Lotus Institute. He will be in the Seattle area leading an offering of the Bodhisattva Mystery School April 9-15. The title of this retreat is: Crossing the Mercy Bridge: 33,000 Faces of Compassion of Avalokitesvara.

Hicks also helps organize Buddhist-related people-of-color events at her sangha and elsewhere. She teaches Yoga for People of Color Healing classes in Seattle, as well as meditation classes. When she is not working as a physical therapist, practicing or teaching, she can be found working out or moving her body in the great outdoors.