The Way of the Writer: Charles Johnson about

Art, Dharma, Race and Political Action

Written by: Steve Wilhelm

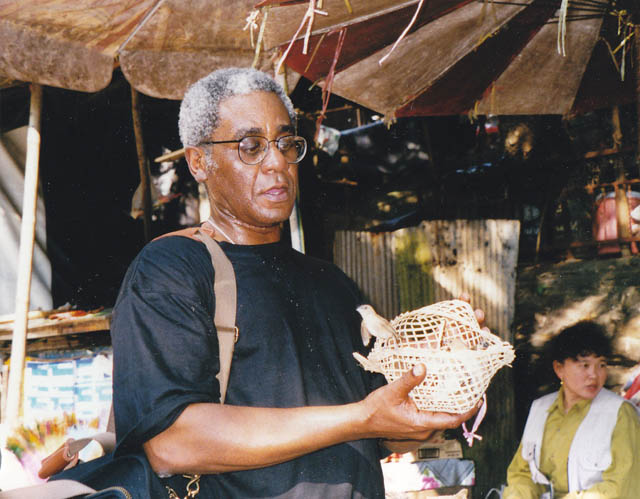

Charles Johnson frees a bird outside a monastery in Chiang Mai, Thailand, during a 1997 trip there.

Photos: Courtesy of Charles Johnson family, Humanities Washington

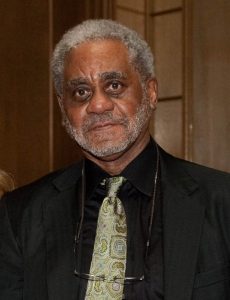

Charles Johnson is simultaneously a leading author, a Buddhist, and holds a doctorate in philosophy.

Johnson has won multiple awards for his many works of fiction and non-fiction, as well as screenplays, children’s books and book reviews. He has received fellowships from the MacArthur Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, and the Guggenheim Foundation.

For 18 years Johnson has annually written a short story, many of them Buddhist-themed, for the yearly Humanities Washington fundraiser.

For 33 years Johnson taught creative writing at the University of Washington.

He also is a significant voice in Buddhist circles, often appearing in workshops and panels, and frequently writing for leading Buddhist periodicals.

Johnson lives in Seattle with his wife.

How did you get started in Dharma practice?

“There are lots of ways we come to the Dharma as individuals. In my case I came in my teens to the Dharma, because of my love of Buddhist art.

“I was a visual artist planning to be a cartoonist and illustrator, and the art that I saw, the 10 Ox-herding pictures, the Zen art, was just stunning to me.”

Johnson started meditating at 14, and then dedicated himself to study until he found a teacher.

When did you start meditation, and how did that go?

“I first practiced meditation when I was 14 and it was a powerful experience, but I didn’t have a teacher. What I decided I would do instead of practicing meditation was to study. Through my teens and 20s, while I was in in college, I did an academic study of Buddhism, Hinduism and Taoism.

“Shortly after I starting teaching here (at the University of Washington), after I got tenure around 1980, I found the teachers I needed for the practice of meditation, here and in San Francisco.”

What’s the connection between meditation and artistic creativity, and the relative limits of the latter?

“You’re not going to achieve enlightenment through the arts, but the arts point an artist on the path, and provide a ground for later spiritual development.

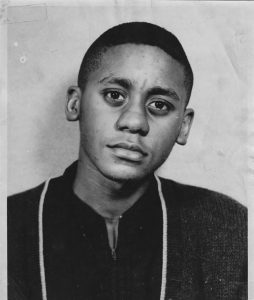

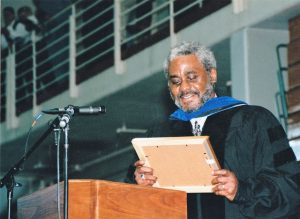

Johnson was awarded his doctorate degree by Stony Brook University in New York. His dissertation became the book “Being and Race: Black Writing since 1970.”

“I work all day long, and for decades, with words, stories, narratives and language. One of the things that has happened with my practice is I have a suspicion of language and stories, a suspicion about the danger we can fall into with the stories we tell ourselves about ourselves. Awakening is something you can’t describe, as Thich Nhat Hanh has often said. It is non-verbal, non-discursive.

“I tell stories, and I like to call them Bodhi drama. I hope they are fingers pointing at the moon, but they’re not the moon, and I always keep that I mind. As much as I love art, like the paintings in this room, that is not the ultimate goal.”

What’s the importance of the mindfulness movement to people in this country?

“There is a mindfulness movement in America. If you can bring that to children K-12, especially when they hit puberty, you give them a gift that is wonderful. Mindfulness training I believe it is for everybody, literally.”

Johnson, playwright August Wilson, and Indian scholar Nibir Ghosh, often met at the Broadway Bar and Grill on Seattle’s Capitol Hill for marathon discussions.

How did you bring mindfulness and meditation into your 30-year-career as a professor of creative writing at the University of Washington?

“I never set foot on this campus for 33 years, until after I either did meditation or mantra…it was usually mantra.

“I needed to be able to get me out of the way. By the time I would get to the parking lot I would have centered myself, so I could leave whatever was on my mind, thinking about yesterday or tomorrow, outside the classroom door. My office used to be on the fourth floor, and I would sit and meditate in my office before class.”

What’s your advice for maintaining a practice in the middle of a complex creative life?

“Formal sitting is important, and I love it. But the point is we should be in a meditative state all day long, all day long when we’re conscious, and ideally when we’re unconscious as well. The formal sitting is a way to charge your battery. When you get off the cushion that’s when you should have that same meditative consciousness, in every little thing we do.”

What’s your connection, or not-connection, with Buddhist groups in the Seattle area?

“I support as many Buddhist organizations as I possibly can, in every possible way, but I don’t need to sit with a group. I don’t feel the need to sit with a group at this moment.

“The Sangha, like anything else in Buddhism, is a tool. At some point in terms of one’s evolution on the path, you don’t need certain tools. It’s like the boat, the metaphor that takes you across the water to the other shore. You don’t carry the boat around on your back.”

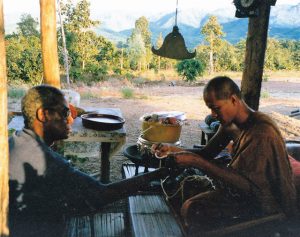

A Thai monk offers Johnson a blessing cord during his 1997 trip.

What was your experience of Thailand, when you traveled there in 1997 to write an article for a Microsoft travel magazine?

“Being in a Buddhist country, everywhere I looked I could see the impact of Buddhism, which was a revelation experience for me. Politically it (Thailand) is terrible, but the richness of Buddhist tradition is just wonderful.”

From that experience, and contact with Asian and Western Buddhists since, what do you see as differences or not?

“This East-and-West division is an illusion; we’re talking about human beings. When human beings ask themselves certain questions in the East and in the West they very often come up with the same answers, because we all have the same mental equipment despite our cultural differences.

“I believe Asian temples would do well, and convert dharma centers would do well, to talk to each other. We’re not that very different. We’re all going to die. We don’t realize how soon it is we’re all going to die.”

Johnson’s grandson Emery Charles Spearman, who just turned five, starting his own meditation practice.

What is your vision of the link between the Dharma and work in the political sphere?

“I truly believe the next stage in our quest for liberation, after the civil rights movement, involves the Dharma and an appreciation for what the Dharma is. The Dharma is nonviolent, non-materialistic, and non-dualistic.

“If we look at some of the writings of Martin Luther King Jr., that emphasis on interconnectedness is there. He talks about a network of mutuality, between all people.

“There are spiritual connections between King’s vision and the Dharma, and I tried to dramatize some of that in novel I published in 1998 called “Dreamer.”

How has your own political thinking evolved, from your radical roots in the 1960s?

“I was a Marxist. But there were problems I had with that, in terms of my growing commitment to Buddhism, to non-violence, and to certain truths that were not compatible with the Marxist vision and ideology.

“I have over the course of my life, as an American, had to evolve my questions about political activism during the civil rights era, the black power movement, with spiritual practice. I constantly think about that. This is why I’m Buddhist, it gives me a focal point for dealing with these issues.”

How do think about political action and the Dharma?

‘The best thing to do is look at Thich Nhat Hanh’s principles of engaged Buddhism. It’s online, and says everything one needs to say about activism, political parties, and the relationship of Buddhist practitioners to the political world.

“The Bodhisattva goal is to see happiness and freedom from suffering for all sentient beings, but in order to do that you have to prevent people from hurting other people. We take a vow, no killing, and we should work to prevent other people from killing, if possible, from exploiting others, or exploiting the environment. Those are all very important concerns.”

How do you understand climate change, and human response to it, from a Buddhist viewpoint?

“You can’t deny the changes in this planet’s climate and the accelerated changes….you can’t deny any of that.

“I think it is a network of influences, I think it is interconnected, I think everything interconnects. We can’t always understand all of the causal influences that make things happen.

“We talk about dependent origination. Yes, nothing comes into being by itself. There are numerous influences, and the climate is one of them.

“I think Buddhists are sensitive to that, the general population may not be sensitive to that, in a way that might actually cause all of our downfall.”

How does your writing support the Dharma, and also racial diversity?

“I certainly hope everything I write does that, whether it’s a story on an essay. To me the writing I do is seva, a form of service and sacrifice. It isn’t for money, it isn’t for attention, it isn’t for fame and fortune, this is my spiritual practice. It’s best for me because I know my nature, my nature is that of an artist, and that’s what I do, I create.

“This is how I communicate with others. I don’t often give Buddhist lectures. I’m not a Buddhist teacher like, say, my friend Lama Rangdrol. I’m a lay Buddhist practitioner who took his vows in the Soto Zen tradition, an upasaka, who happens to be an artist.”

In these divisive political times what response is needed, from Buddhists, toward people of other faiths?

“I believe that at this moment in our history, we definitely need more communication with American Muslims. I think their portrayal in the media is painfully divisive and incorrect very often. There has to be interreligious communication between Christians, and Buddhists, Muslims and Sikhs. We need to talk to each other as human beings.”

What role does your Dharma practice now play in your life; how central is it?

“It’s everything, it effects everything that you do. You can be 68 or 16, everything we do should be reflective of the wisdom of the Dharma we have been privileged to receive.

“My true feeling is that being a Buddhist is a privilege, hearing the Dharma is a privilege.

“What you do in terms of your practice, your mindfulness, the control you have over mind, body and spirit moment-by-moment, it’s like art, it’s like having your life as a canvas. Through your practice and rational deeds, you’re painting a picture of yourself.”

How has the Dharma changed the choices you make?

“There are certain things I cannot do, and never will be able do, because of practice. Buddhism is a reconditioning away from the negative conditioning we have in society, and I say this as a black American. What you do is you undo that conditioning, and you recondition yourself.

“So you are not going to kill, you are not going to steal, you are not going to lie, you are not going to consume alcohol to intoxication, or engage in sexual misconduct. You are not going to elevate self over others, you are not going to dwell on the faults of others, you are not going to be stingy rather than generous, and you are not going to do anything that will damage the three jewels.”

Is the Buddhist goal of liberation relevant, even for people who are oppressed?

“This is about freedom ultimately, as a Black American I say this, it’s all about being free. The Buddha Dharma offers freedom no other religion does, freedom even from itself, from the doctrines of the Buddha Dharma.”

What’s your own Dharma goal?

“I want this to be my last time around. I don’t know anything about reincarnation. I have been told by good teachers to not even talk or think about reincarnation.

“But if reincarnation is true, I want this to be my last time around.”