How Two Black Women Utilize Buddha Dharma

Written by: Genevieve Hicks

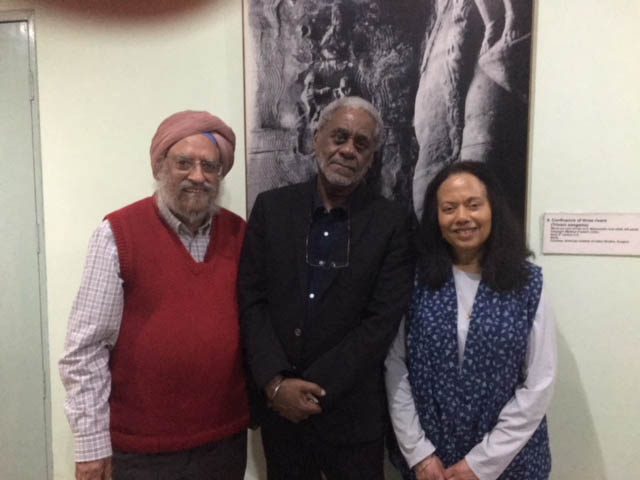

Sharyn Skeeter meeting Sunita Rani at Agra College in India, February, 2018. (Charles Johnson is in background.)

Photos by: Genevieve Hicks, Steve Wilhelm

I believe that there is something specifically in Buddhist practice for Black Americans. How can there not be? It’s about suffering and the end of suffering.

Our particular brand of suffering comes from being born into these black bodies, in a country that was forged, from its birth, in anti-blackness.

How have other Black American women found their way to this practice? What has Buddhism done for them lately? Tracy Stewart and Sharyn Skeeter are two Black women, who agreed to talk with me about their experiences.

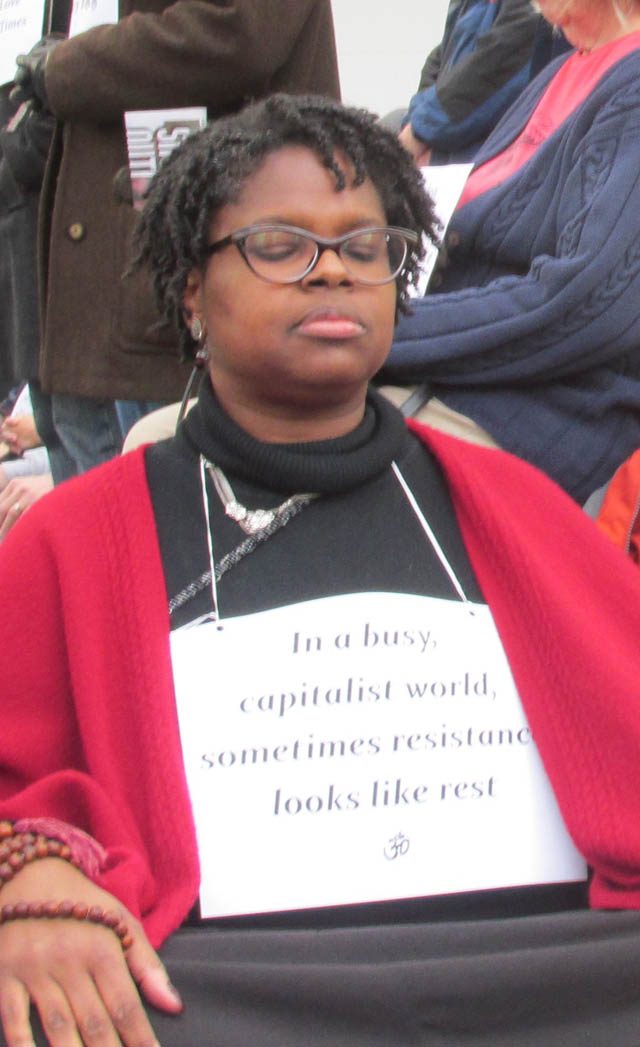

Tracy Stewart

Tracy Stewart is the adopted daughter of two white parents. As a young girl, growing up in Beavercreek, Ohio, she had been interested in going to church. Her family obliged her by returning to the neighborhood Methodist Church they had attended in the past.

Soon after the family started attending, a racially motived comment by a fellow churchgoer nipped that family project in the bud. They never returned.

Stewart was first exposed to Buddhism in 1987 while attending Ohio University in Athens, Ohio, through a Hare Krishna event on campus. These events were known for the abundance of free delicious vegetarian food and short talks, during which attendees were exposed to different world religions. Stewart soon became what is known as a bedstand Buddhist, one who reads about Buddhism in the privacy of their bedroom.

In 2008 a personal crisis led her to broaden her practice, by weekly attending a Zen-based meditation center, in Yellow Springs, Ohio.

Flash forward to Seattle 2018. Stewart is now in a leadership role with the Buddhist Peace Fellowship Seattle chapter, and practices with several Seattle Buddhist sanghas. She uses mindfulness extensively in her mental health therapy practice.

Stewart is quick to share her view that secular mindfulness has been ripped off from Buddhism, plucked out and monetized. She believes that this repeats historical colonial practices and appropriation, within Western Buddhism.

She poses several questions. How do we practice without appropriating, in a way that is respectful and doesn’t maintain patriarchy, even though our teachers may have learned in a patriarchal system? Is there a way of practicing that honors the woman, the feminine of Buddhist practice, and doesn’t perpetuate patriarchy?

Who are Stewart’s teachers these days? She spends most of her time listening to teachers who are people of color, saying, “Our experience is just different from the Euro-majority. “

What does Buddhism have to offer us as Black women?

“Ease,” she said. “Life is a series of pleasant, unpleasant and neutral events, and Buddhism can help relieve the suffering of the struggle, our struggle.”

And then to my surprise she added, “Not that our suffering is any more or worse than others though…Different aspects of the same issues show up for many people – poverty, racism, sexism. I feel like anti-blackness is the worst, and then I think about conditions of indigenous women in this country. “

“I retreat from that position, I don’t want to do a suffering Olympics and yet we know that by design, systems in this country have been set up in a way for people of the African diaspora to be kept at the bottom. That is part of the design of this country. “

While I know that this is true, I also know that people on reservations are suffering immensely, the disappearance of indigenous woman is out of control. I have hesitancy to say that black women suffer the most from racism in this country.”

When pressed about why she calls herself a Buddhist, she shares it is because she starts her day with some aspect of the eightfold path not limited to meditation or studying sutras. She finds the teachings of the Buddha liberating, comforting, normalizing of her experience, and connecting her to other human beings.

A tool that she offers her clients, most of whom are Black women, is the acronym STUF. When suffering is present, notice what sensations are showing up, what thoughts you having, what you have the urge to do, and what feelings are present.

Sharyn Skeeter

Sharyn Skeeter is a retired educator, writer and editor. She has practiced primarily in Tibetan Buddhism lineages. She recently returned from an academic lecturing trip in India with her friend and colleague author Charles Johnson, during which she was able to visit historic Buddhist sites and temples including Bodhgaya and ancient Nalanda.

Skeeter describes her India experience as thrilling and meaningful in the context of her Buddhist practice. This trip helped reinforce her strongly-felt sense of interconnectedness. She acknowledges how privileged she was to be a part of such a trip, and also acknowledges that she witnessed suffering on this trip, the likes of which she will not forget.

Born of a mixed-race mother and black father, Skeeter notes that depending on where she is in the world, she can be seen as Ethiopian, indigenous or East Indian. She has a strong connection with her maternal grandmother, who is Black American-Mohegan, and Skeeter incorporates indigenous heritage into her practice of Buddhism.

“I was raised ethnically Black,” Skeeter said, “So that is what I am as far as social definition, and as far as the way I conduct myself in this country.”

In a way, practicing Buddhism opens her to the experience of being part of everyone and everything on this planet; even though there are those who try to tell her that she is not.

For Skeeter Buddhism is a daily practice, is it just being mindful during the day, to “Look at the sky, look at my dog, look at those flowers.” These “informal practices” are more important, she said, because they’re day-to-day living.

Some of the formalized practices of using beads with mantras, or taking time to sit quietly for 10 minutes, are also useful. Formal daylong initiations, deity rituals and chanting, which are a central part of the Tibetan lineage, also have a place in the way she practices.

People misunderstand praying and meditation with deities, Skeeter said.

“I am not worshiping deities,” she said, “I am seeing the qualities of the gods in myself. When I do these deity practices it really forces me to look into whether I have these qualities within myself, and what do I need to change inside of me in order to be more like this ideal.”

An example would be White Tara meditation, in which you visualize the goddess Tara and the qualities and the symbols associated with this goddess. Then you merge yourself with the deity. You are taking on her wonderful qualities.

Buddhism is a tool. It’s a tool to help figure out how to be a better self, that’s all Buddhism is. Along this path we are all on, how can we do it a little bit better, how can we free ourselves – from whatever our suffering is. Buddhist practices offers ways to explore how we can make ourselves free. It allows one to feel joy, even when things all around are not so joyous.

“Buddhism is something I live,” Skeeter said. “I just live it – when my late husband was sick, learning how to understand impermanence and compassion; when my son and his wife, who were living on my property, decided to leave – I had another opportunity to work with impermanence and letting go.”

She offered a critique of the mindfulness craze. Mindfulness in the secular world is taking something that is part of a larger tradition out of context. Are there any core values that go with this mindfulness? It should be part of something larger, not used as an isolated practice. There needs to be an ethical foundation for any kind of mindfulness.

About Tracy and Sharyn:

Tracy Stewart invites you to support Buddhist Peace Fellowship Seattle chapter.

Sharyn Skeeter is a former fiction/poetry/book review editor at Essence magazine, and former editor- in-chief at Black Elegance. Her novel, “Dancing with Langston,” is due out in fall 2019 (Green Writers Press).

Genevieve Hicks practices in the tradition of Thich Nhat Hanh at the Mindfulness Community of Puget Sound (MCPS) in Seattle. In addition to being an active member of the MCPS, she helps organize Buddhist-related people of color (POC) events at her sangha and elsewhere. She also organizes and teaches yoga for people of color healing classes in Seattle, as well as meditation classes. Her wage-paying job is as a physical therapist. When she is not working she can be found hiking and moving her body around indoors and outdoors.