Northwest Buddhists Attend Ancient Ceremony at California Nun’s Training Monastery Aloka Vihara

Written by: Holly Griswold

Eleven monastics — fully ordained bhikkhunis, novice samaneras, and trial-year anagarikas in white robes — stand in line and give thanks for the food they have been offered on Kathina day.

Photos by: Holly Griswold

Three Northwest women traveled to the Aloka Vihara Training Monastery in California last fall, for the nuns’ annual Kathina ceremony.

The Kathina ceremony, a tradition carried on since the time of the Buddha, is an opportunity for the lay community to offer monastics cloth for robes, and other monastic requisites.

We went because we wished to support the full ordination of women in the Theravada tradition, and because we were curious to see how the bhikkhunis were settling in and growing this new monastery.

We also went because we already know each other, as a collective of women who have come together every Monday morning for the past four years via Skype. Together online, we chant morning puja, meditate and give merit.

While most of us live in or near Portland, others hail from the Oregon Coast, the Columbia River Gorge, Spokane and England. We affiliate with the Theravada forest tradition of the Ajahn Chah lineage, and with the broader Theravada teachings. Most of us feel a connection to Abhayagiri Monastery, in Northern California.

We also went because we believe ordination of women balances out this Theravada tradition that we love, and aligns us today with what the Buddha knew was best. We feel that only through the full participation of both genders, can the full knowledge of what the Buddha taught be available to all. We are so grateful for to have this women-run teaching monastery on the West Coast. We just had to go check it out!

This is an exciting time for those who feel at home in the Theravada forest tradition, because the bhikkhuni sangha is being restored after a long hiatus.

Theravada adheres to the rules set out by the Buddha called the vinaya, and is firmly planted in the Pali suttas (the scriptural canon). It has a culture of the lay community supporting alms mendicants. Theravada teachers focus on what the Buddha taught about suffering, its causes, its cessation and the path of liberation.

The four-fold assembly

Originally the Buddha said there should be a “four-fold assembly” of practitioners, made up of female and male monastics, and female and male lay practitioners. He was unequivocal about this intention, stating very shortly after his awakening- even before he began teaching- that a four-fold sangha was an essential part of his plan.

The first women were ordained by the Buddha in 500 BCE. Sadly female monastics were under pressure, and their presence disappeared for almost 1,000 years due to political and cultural decisions.

Beginning in 1988 ordination for women was revived. This was made possible by ordination from Asian nuns who still held the ancient bhikkhuni lineage, and by Theravada monks.

Now the bhikkhuni sangha is gaining momentum and numbers. Full ordination is once again available for women globally, and available on the West Coast of North America due to Aloka Vihara.

Ayya Anandabodhi and Ayya Santacitta are the founders of Aloka Vihara. They came here from Amaravati Monastery in England, at the request of Buddhist practitioners in the greater San Francisco area in California. They lived in a house in San Francisco for the first five years, before feeling confident that support was strong enough to start a monastery.

In 2014 Saranaloka Foundation purchased land with a house near Placerville, California, about 50 miles east of Sacramento. The location is remote, at the end of a long gravel road, snugged up against the wild Bureau of Land Management forest of tall pines and hardy oaks. What pioneers they are. What a wonderful, strong desire among the lay sangha to support women to fully ordain!

The monastery was primarily established to train bhikkhunis (full-ordination nuns), in the Theravada forest tradition. It is also a place where lay Buddhists can learn, practice and serve.

The practice emphasizes simplicity, renunciation, service, and an orientation towards learning from the natural world, all held within a context of the Buddha’s teaching.

The Kathina is an annual event that celebrates the interdependent relationship between the ordained nuns and the lay community. While the nuns are supported entirely by lay community generosity, the nuns give back by living in accordance with the vinaya (monastic rules laid out by the Buddha), and teaching the dhamma (what the Buddha taught), to the lay community.

During the Kathina lay people originally gave the monastics special cloth, (the Kathina cloth) to be sewn into robes. Over time people began to see this ceremony as an opportunity to offer other kinds of support to the monastic community, their “four requisites” of food, shelter, clothing and medical care. Just as the monastics dedicate themselves to teaching, both in word and through their way of life, lay practitioners dedicate themselves to offering what it takes for a community of bhikkhunis to thrive.

Work party

We arrived on Saturday to help in a daylong work party. Before working we sat in a circle for meditation, then the nuns and helpers laid out the day’s projects. I noted the easy delegation of tasks, and the respectful and soft banter among the nuns.

Working together with event organizer Emily Carpenter, the resident nuns, and lay people who are beginning their exploration of monastic life, we set up event tents, covered meadow grass with soft, ornate rugs, and carefully wheelbarrowed down the bronze Buddha statue from the shrine room. We raked up crunchy oak leaves, put up signs, prepared seating for the midday meal, and strung many strings of colorful golden Tibetan prayer flags.

The feeling at Aloka Vihara, in the woods and meadows of the Sierra Nevada foothills, is of a nature refuge. The outside world does not intrude in this quiet monastery. Blue Steller’s jays called from high up in the pines, abundant acorns rolled and cracked underfoot like brown marbles, and breezes swirled and sighed along ridges and canyons. Gold oak leaves drifted onto the blond meadow grass where the Kathina tent awaited the next day’s ceremony.

To close out the day we gathered in a circle beneath a giant oak for meditation, settling us with gratitude and happiness for such sweet companionship. The four resident nuns chanted blessings for us all in Pali and English, their soft, gentle voices speaking of harmony, stillness, and strength.

On the day of the Kathina, nuns and anagarikas came from two other women’s monastic communities in the area.

I sure enjoyed seeing 11 nuns before me. I am devoted to supporting monastics. To enable monastics to live and practice as was done in the time of the Buddha keeps this path bright and alive for us all.

A ceremonial meal offering was made to the nuns, who are alms mendicants. Each of us lay-folk spooned a bit of rice into the alms bowls of each nun. Then, after serving themselves from the offered food, the nuns all chanted a blessing for the receiving of food for sustaining their efforts toward liberation/nibbana, and in thanks for our giving of food, that the generosity would bring us merit.

In the Kathina ceremony tent I sat cross-legged, facing the long line of nuns. I was surrounded by 60 lay Buddhists, by grandparents, children and grandchildren playing quietly. The Kathina ceremony settled deep within me. It is a confirmation of the commitment between monastics and lay community, to give and receive in gladness, joy and hope for growing the future of Aloka Vihara Forest Monastery.

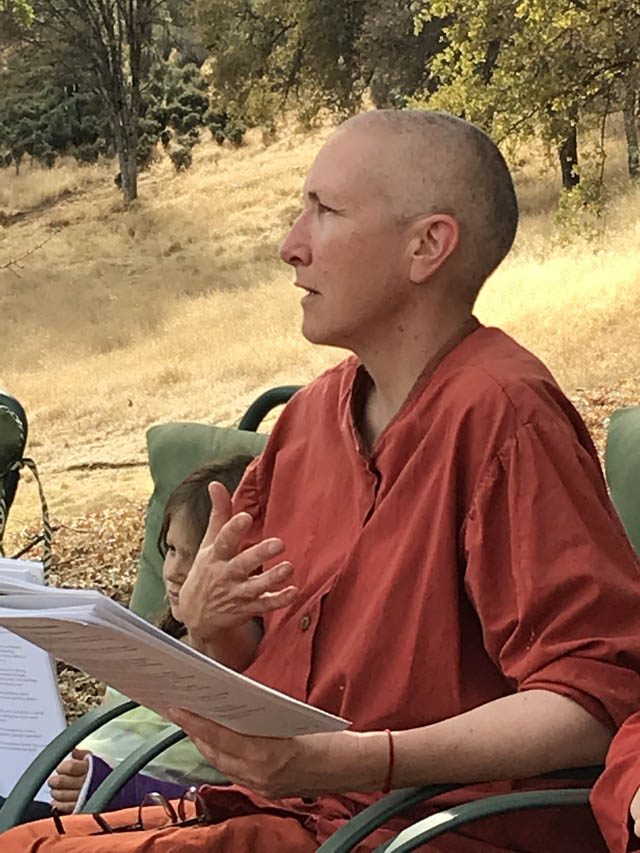

The heart of the Kathina was when the cloth for robes was given by the couple sponsoring this year’s Kathina. Short dhamma reflections were given by six of the nuns. In a time where most dhamma reflections given by monastics are from men, I truly enjoying hearing these bhikkhunis speak.

A highlight was when we all chanted the “Recollection of the Foremost Arahant Bhikkhunis.” This new chant is a song-like affirmation of the attributes of 13 enlightened women acknowledged by the Buddha.

In this chant we describe the attributes of each bhikkhuni, such as how she cultivated meditation, or was foremost in great wisdom, or for her quick intuition, or for “seeing well purified.” We all asked, in joining our voices together in this chant, “that the power of her qualities always be a blessing to us, and the power of her qualities always be a blessing to you. May these and all the other powers of the bhikkhunis dispel fear, sorrow, and illness, and endow us with faith, wisdom and virtue.”

Pacific Northwest Supporters

All are welcome for visits and retreats at Aloka Vihara, arranged in advance. The nuns also teach retreats at Spirit Rock, IMS and other venues, which one can find out about from their website and newsletter.

Support for Aloka Vihara and the ordination of bhikkhunis seems strong and wide. Some of the past and present board members of the Saranaloka Foundation live in White Salmon, Washington, east of Portland, and in the Seattle area.

The stewardship foundation, Saranaloka, was started in 2005 by a group of lay practitioners. The purpose was to bring Theravada Buddhist nuns of the forest tradition from Chithurst and Amaravati monasteries in England to the United States, to teach and to establish a training monastery for nuns in the United States.

In addition Portlander Carpenter in 2015 helped start Friends of Aloka Vihara, as an independent fundraising body to support the development of Aloka Vihara.

In the afternoon, as the weakening autumn sun slanted soft yellow through the dry woods, the Kathina ended. We rose and moved thoughtfully from the decorated tent. We said our good byes to the nuns, novices, and lay friends. We traveled the long route up Interstate 5, back to the lush Pacific Northwest, to our friends on the path and our inspiring teachers.

We feel enriched knowing the future of a four-fold assembly in the Theravada forest tradition is, with our support and the support of many, in good hands and thriving.

Holly Griswold is a Theravada Buddhist, living in the Columbia River Gorge near Hood River, Oregon. I am fortunate to have been part of the lay sangha (community) around Pacific Hermitage in White Salmon (with Ajahn Sudanto Bhikkhu as abbot), a branch monastery of Abhayagiri in Redwood Valley, California. I live in the forest with my husband and a devoted cat. I have been interested in Buddhism most of my adult life. My thanks to my dear spiritual friends for helping write this article.