GenX Buddhist Teachers Gather at Great Vow,

Find Comradeship and Support in their Variety

Written by: David Perrin, Kim Allen, Kyira Korrigan, Sumi Loundon Kim, Yeshe Chödrön

The Panel on Integrity and Enlightenment reflected the gathering’s diversity, including Grace Song, Brother Phap Hai, Roshi Chozen Bays, Lama Willa Miller and Singhashri Gazmuri.

Photos by: Shundo David Haye

On an unusually hot day for the Pacific Northwest, some 40 Buddhist teachers converged on Clatskanie, Oregon, to attend the 2019 GenX Buddhist Teachers’ Sangha Gathering (GBTS).

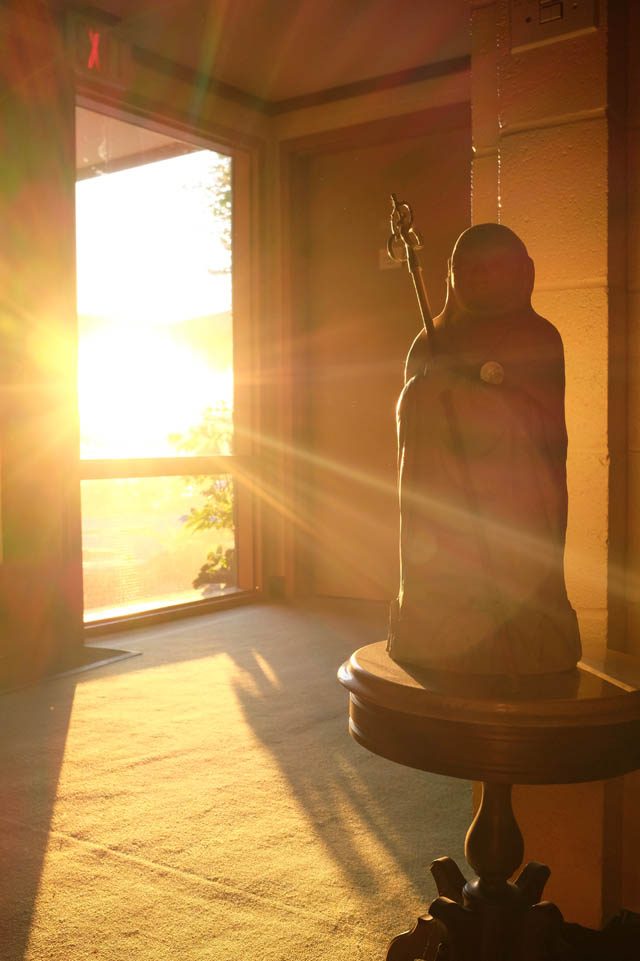

The June 12-to-16 gathering of GenX Buddhist leaders from North America and beyond was hosted by Great Vow Zen Monastery.

In the rare company of other dharma teachers, of similar age and experience, we delved into our theme of ethical transformation. For a few rich days we met amongst the redwood trees surrounding the former elementary school turned monastery, as well as in the zendo, gym, cafeteria, and library—a living metaphor for a generation often characterized by the wish to refashion existing structures.

Together in panels, a keynote speech, private conversations, and group activities, we tackled many inquiries. These included the role of ethics in spiritual transformation, navigating the power dynamics in teacher-student relationships, and the turmoil caused by recent revelations of improper sexual relationships between Buddhist teachers and students in the West.

GBTS grew out of a group of elder Buddhist teachers wishing to pass the torch to a new generation, at a 2011 conference at the Garrison Institute in upstate New York. After that conference leaders of the younger group organized a biennial gathering focused on Generation X Buddhist teachers (defined by the sangha as those born between 1960 and 1982), to extend the experience of community they encountered amongst themselves. The effort carries forward to this day.

Insight meditation teacher Sumi Loundon Kim has attended all the gatherings, and is involved in sangha leadership. She noted that from the start, GBTS cultivated a culture of dharma peers, which she described as, “The intention to put our teacher role to one side and to relate to each other as friends on the path, helping each other learn and grow personally and in our profession.”

As such the gatherings have evolved into less conference and more retreat space. Time is allotted for small-group discussion, walks, rituals and meditation.

David Perrin, a first-time participant at the June gathering, was surprised by how readily he felt at home.

“My Buddhist tradition of Shambhala is primarily a householder tradition, so it was fascinating to take residence in a Zen monastery and meet dharma teachers from all around the world,” he said. “I made many new friends and enjoyed meaningful conversations and exchanges.”

Learning about each other, individually and collectively, is a hallmark of the gatherings. This begins with open discussion of the very parameters governing group norms during and after the gathering, on topics ranging from logistics to privacy issues. Through open engagement the members co‑create trust and conscious community.

“There is a lot of wisdom in the room when you have a group of dedicated Buddhist practitioners hoping to share and to learn from each other,” said Kyira Korrigan, a Buddhist prison chaplain who has attended all five of the gatherings. “When everyone is your peer, you can be open in a way that isn’t always possible in other relationships.”

This dynamic communication, Perrin quickly learned, meant that the theme of the conference, ethics, “was relational, and focused on telling our stories.”

“Open and honest sharing is predicated on trust,” he said. “As a newcomer I immediately sensed that there was a lot of trust already in the room. Returning participants rekindled existing friendships from past gatherings. This made me feel safe and grounded. I could tell how much love and respect was in the monastery.”

Korrigan, who stopped teaching in her previous sangha due to ethical problems in leadership just before attending her first GBTS gathering in 2011, felt welcomed and supported there by people worthy of respect and trust.

“The most nourishing aspect of participating in these gatherings is that I have not felt alone,” she said. “In Buddhism lineage is irreplaceable, which can leave refugees of teacher misconduct isolated. At the first Gen X gathering I was just three weeks gone from my original Buddhist community. I feared that I would have no place to belong. Gradually, surrounded by beautiful, like-minded peers who are also teachers, I learned that I was never separated from my path for an instant, even when things were darkest.”

From the start, GBTS shared a commitment to explore such charged topics as exclusivity and oppression in dharma centers.

At first blush it might seem antithetical for spiritual spaces, Buddhist centers, and places of meditative refuge to be tinged by racism, sexism, homo- and trans-phobia, ableism, and other pernicious forms of superiority. But many participants shared the pain of encountering such biases in their home Buddhist communities.

Awakening to our own and others’ vulnerability is part of how this sangha bonds over social issues. In fact GBTS aims for diversity in many ways: across Buddhist lineages, ethnicity, race, sexual orientation, and balance between genders and monastic or lay status. In particular GBTS honors a range of lineages established in the West.

The 2019 gathering attracted roughly equal numbers of teachers from the Theravada, Mahayana, and Vajrayana traditions of Buddhism. Attendees included teachers from the Triratna Buddhist Community founded by British-born Sangharakshita, as well as Asian lineages such as Won Buddhism and Jōdo Shinshū.

While gatherings provide time for teachers in the same lineage to confer, the sangha values cross-fertilization among lineages. This lessens the risk of sectarianism, and enriches individual understanding of the Buddhadharma. Often deep friendships and co‑teaching opportunities emerge from this ecumenical orientation.

Zopa Christopher Rose, a Tibetan Buddhist lama and second-time attendee, said he was initially somewhat puzzled by the atypical horizontal power structure he encountered at his first gathering in 2017. Now he prizes the fact that “the equal value of each and every voice is for real, something foundational to the sense of belonging that this sangha offers.”

Rose said in his experience, “being with those dedicated to the Buddha’s way, and seeing how they live the wisdom of the path to bring benefit to the world in diverse ways,” is one of the most salient benefits of the gatherings.

Indeed, a potent aspect of gathering diverse dharma teachers from different traditions is the chance to recollect what drew us to this life-transforming work. Each participant brings their own intimate understanding of the deeper dimensions of the Buddhadharma.

Amidst discussions of the everyday issues of teaching, communities, or society, people found moments to connect through what could be called the timeless or transcendent, a nourishment unique to such gatherings.

After five gatherings GBTS is maturing. Although existing committees manage various sangha activities, the community discerns the need for more cohesive organizational structure to support the group, and to allow it to take on the role of voicing sangha concerns in the larger Buddhist world and beyond.

At the June gathering the community tasked an interim council with shepherding it toward shaping a structure. The intent was to formalize and advance the sangha’s informal but firmly established expectations for a continuing culture of relating as peers, inter-lineage orientation, and true inclusivity.

In his thoughts Perrin crystallizes the deeply personal, spiritual, and communal impact of the gathering.

“I had not expected that my own pain, disappointment, and bewilderment regarding sangha and teacher relations would not only be welcome, but also met with open and honest sharing by others,” he said. “It is a rare opportunity when peer colleagues, of any vocation, can meet in a non-hierarchical, non-judgmental, respectful, confidential space, to share deeply around matters of both heart and mind. I left the GBTS gathering with new inspirations, new connections, and a feeling of shared humanity with my fellow participants.”

David Perrin is a meditation teacher and mentor in the Shambhala tradition, as well as a MNDFL lead teacher and director of the MNDFL teacher training. He is also a creative arts psychotherapist and a trustee of the Perrin Family Foundation supporting youth social justice projects in Connecticut.

Kim Allen offers classes, sutta study, and weekend teachings in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Kyira Korrigan serves as a Buddhist chaplain in the federal prison system in British Columbia and holds a master’s degree in Buddhist studies. She is an authorized lay dharma teacher training under Ven. Pannavati, and is working toward Dharmacharya ordination in the Embracing Simplicity Contemplative Order.

Sumi Loundon Kim is Buddhist chaplain at Yale University.

Yeshe Chödrön (Ivonne Prieto Rose) is a Tibetan Buddhist lama and translator of dharma from Tibetan to English and Spanish in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and at the Rigpe Dorje Institute at Pullahari Monastery in Kathmandu, Nepal.