Consecration of Phagtsok Gendun Choling Temple

Brings Essence of Tibetan Tradition to Northwest

Written by: Brian Hodel

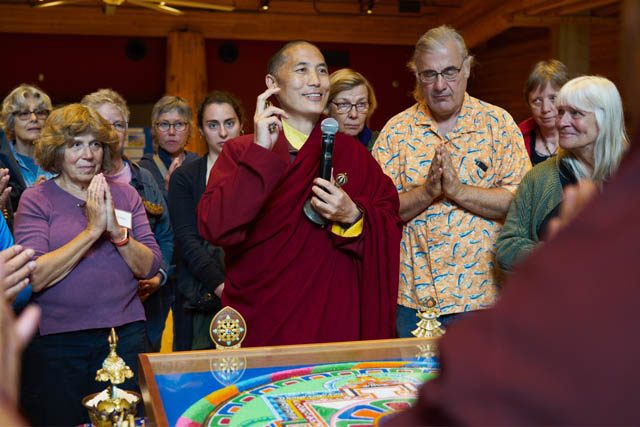

Dza Kilung Rinpoche presiding over the consecration of the temple.

Photos by: Li Mingyang

Tibetan Buddhists came from around the world for the May 30 to June 3 consecration of the new Phagtsok Gendun Choling Temple on Whidbey Island, Washington.

Supporters of Tibetan Lama Kilung Rinpoche funded construction of the wooden 5,000-square-foot temple, to support his teaching program in the West. Whidbey Island is in the Salish Sea, part of which is called Puget Sound, north of Seattle.

Until now activities of Kilung Rinpoche’s organization, Pema Kilaya, were restricted to a modest one-story building. The new temple, with its beautiful shrine room, spacious kitchen facilities, gallery reception area, dining hall, library, meeting rooms and offices, will allow Kilung Rinpoche and the sangha to expand both its membership and the scope of its activities.

Kilung Rinpoche, the founder of Phagtsok Gendun Choling (Dharma Land of the Great Practitioner), is from a new generation of Tibetan masters. Because he simultaneously maintains two headquarters—one at Kilung Monastery in his native Dzachuka, Tibet; and since 2007 at the Pema Kilaya sangha based on Whidbey Island—he has been able to harmoniously blend his ancient tradition with the casual, tech-savvy modernity of the Northwest. The majesty of that synthesis was displayed in the dedication of the new temple.

Many days of dharma practice

The ceremonies surrounding the dedication of Phagtsok Gendun Choling were extensive and based on the deity practice of Vajra Kilaya, a wrathful emanation of enlightened activity.

The May 30 Vajra Kilaya empowerment was preceded by eight days of practice by sangha members, under Rinpoche’s guidance. This was followed by a drupchen (literally: “great accomplishment”) based on an elaborate Vajra Kilaya practice repeated over four days.

Approximately 100 people took part in these practices, with more than 140 attending the June 3 closing. Participants came from Taiwan, Korea, Denmark, Germany, South America, Canada, China, and the U.S.

Following the ceremonies, on June 8 and 9 the seven Tibetan monks invited by Kilung Rinpoche for the consecration created a sand mandala in the temple for a public open house.

During this open house Rinpoche gave two talks: “Prayers for the Earth and All Beings,” and “Sand Mandalas—Sacred Art of Tibet.” As part of a tour, the monks also created sand mandalas at the University of Washington in Seattle, and in Bellingham.

Sunlight streaming from large windows and skylights bathed those entering the temple for the consecration, reflecting off statues, thangka paintings, Tibetan rugs, arrays of colored glass statuettes, the sand mandala, and other traditional Tibetan decorations.

The thick wooden pillars and beams outlining the shrine room’s interior are covered with delicate traditional designs by a renowned Tibetan carver. The gold painted walls and light brown carpet and floor add warmth to the spacious hall.

A temple melding Tibetan and Northwest themes

It was Kilung Rinpoche’s wish to build a temple in harmony with the environmental characteristics of the Northwest. During the consecration ceremony he explained to attendees how he began by sketching designs on napkins during long flights between Asia and the United States.

Rinpoche didn’t want to simply import Tibetan designs, but rather to incorporate those with Northwest building styles. The temple, he said, was to be “in harmony with nature,” and “a cause of happiness for all beings.”

In 2012 possibility became reality when Lynn Hays and Nancy Nordhoff—two Whidbey Island philanthropists who had already provided the land—promised to fund the temple’s construction. Additional property was purchased by the sangha.

The final design was the result of an interplay among Kilung Rinpoche, Seattle architect Art Peterson, and local builder Damon Arndt. Together they produced a seamless blend of modern, low-profile, Northwest-style wooden construction, with Tibetan Buddhist architecture and decoration.

The low and long 5,000-square-foot, shake-shingled building is crowned by a vaulted, three-tiered ceiling over the gonpa, the heart of the temple. Each level has symbolic significance—the lowest representing the nirmanakaya (the relative level of the physical universe), the middle the sambhogakaya (a more subtle manifestation), and above it all the dharmakaya (the ultimate and most subtle aspect of reality).

The inner meaning of fierce compassion

The experience of the consecration event was intense. Assisting Kilung Rinpoche were a khenpo (senior teacher-scholar) and six monks and lamas, who led the chanting with traditional Tibetan instruments including oboe-like gyalings, small trumpets called kalings, thunderous low-pitched tung-chen horns, hand cymbals, and a hanging drum. Bells and small, hand-held damaru drums wielded by the participants added to the powerful atmosphere.

The monks also performed traditional costumed dances outdoors. Ritual fires accompanied each day’s opening practice.

Orchestrating the entire days of consecration, the slow, subtle, dance-like movements of the chöpön—the master of ceremonies—were mesmerizing.

But beyond this rich and even overwhelming presentation, it was Kilung Rinpoche’s commentaries that brought home the significance of this event, and of the Vajra Kilaya practice itself. Shifting back and forth easily from his role as traditional vajra master to informal spiritual friend and commentator for his students, he revealed the inner meaning of the practice step-by-step and with great clarity.

Those familiar with Buddhism know that wisdom and compassion are the “two wings” of Buddhist practice. But what of the elaborate and sometimes-frightening imagery found in the Tibetan tradition?

Kilung Rinpoche said that the abundant, colorful, and threatening images, the chanting and loud musical interludes, and the pungent and varied incense, can shock and astonish the practitioner into a direct experience of the non-dual state—of enlightened consciousness.

“Rather than resisting,” he said, “we can take it in.” This approach, he continued, might be applied to situations that occur in normal life.

When the liturgy asks “that the demons be destroyed,” this ultimately refers to our own inner demons of anger, ignorance, desire, pride, jealousy, and so forth—the negative habitual tendencies that keep us from wisdom and enlightenment. Therefore the destroyer—in this case the wrathful deity Vajra Kilaya—embodies wisdom and is driven by compassion.

The Vajra Kilaya practice is important to all of the Tibetan Buddhist lineages. But it has particular significance to Kilung Monastery, which sits at an altitude of some 15,000 feet in the Dzachuka region of Eastern Tibet. There it is associated with Patrul Rinpoche (1808-1887), a native of that region and a teacher known in the West as the author of the Tibetan dharma classic “Words of My Precious Teacher.”

Patrul Rinpoche was the student of first Kilung Lama Jigme Ngotsar Gyatso, who was in turn a disciple of the great Rigdzin Jigme Lingpa (1729-1798)—the author of the Vajra Kilaya sadana (text) used in the drubchen described above.

Jigme Lingpa was also the founder of the Longchen Nyingthik lineage for the Nyingma school of Tibetan Buddhism—the lineage of Kilung Rinpoche and of the Pema Kilaya sangha of Whidbey Island.

Thus the consecration not only brought alive the beautiful new Phagtsok Gendun Choling Temple, but also transferred the heart essence of Tibetan Buddhist practice to a new home in the Pacific Northwest.

In doing so Kilung Rinpoche planted the temple, and all that it signifies, firmly on Western and specifically Pacific Northwestern, soil.

Brian Hodel is a long-time student of Kilung Rinpoche and of Vajrayana Buddhism. He edited Rinpoche’s book “The Relaxed Mind.” Hodel traveled to Whidbey Island from Brazil, where he currently lives, for the consecration of the new temple.