Children Learning to Notice what They Notice:

Introducing Mindfulness at the Art Gallery

Written by: Margo McLoughlin

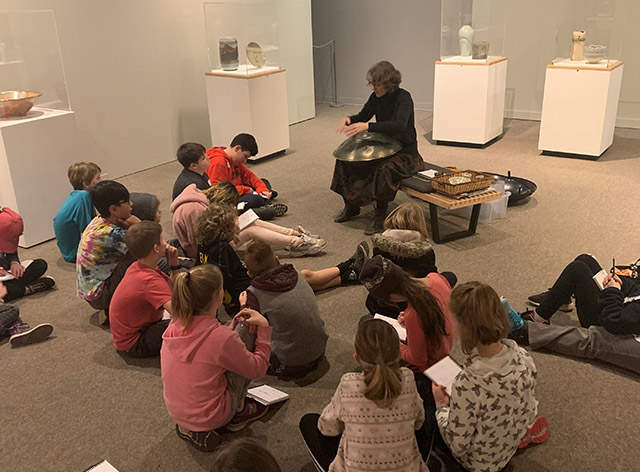

Margo McLoughlin telling a story with musical accompaniment.

Photos by Hilary Potosnak

Between October of last year and the middle of March, more than 700 children came to the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria to participate in a new program called “The Art and Heart of Mindfulness: Discovering the Gift of Perception.”

The gallery sits at the top of Moss Street, a short drive from downtown Victoria in British Columbia. Surrounded by Garry oak and Douglas fir, the original building is a Victorian house, beautifully trimmed in grey-green and burgundy. Beside it stands a low structure of post-modern concrete.

Margo leads a school group in a guided visualization where they become the trees in an Emily Carr painting.

Art galleries are all about looking and seeing, which makes them perfect sites for learning the skill of mindfulness, the ability to attend to our present-moment experience with an attitude of interest and openness.

I developed the program to put into practice some ideas I’ve been reflecting on as an elementary school teacher and a storyteller: How does one introduce children to mindfulness as a skill for developing observation skills and curiosity? How might storytelling play a role in that?

There is a lot to notice at an art gallery, even before you step inside. Besides the difference between the two buildings, there is also the soundscape. Drawing children’s attention to sounds prepares them for stepping inside the gallery to practice other kinds of noticing. What sounds do we hear standing under the trees in 2020 that we might not have heard a hundred years ago?

On a sunny spring day, I asked one group of children to find a spot in the sunshine and notice the feeling of warmth on the top of their heads or shoulders. Looking up at the limbs of the fir and oak trees, and beyond them the clouds and the sky, we imagined what a squirrel might see looking down at us.

Children cultivating mindfulness by drawing pottery.

What we see depends on where we’re standing and how we direct our gaze. Each of us has a unique viewpoint, both literally and metaphorically. No one else sees the world the same way we do. This discovery reminds us to value our own perspective and to learn about others’.

Over the course of delivering my program, I realized an art gallery is a wonderful place to explore the gift of perception with children, and to help them make important links between perceiving and the practice of mindfulness.

A number of well-tested programs now exist for introducing mindfulness to children in the classroom setting. In one of these, Mindful Schools, an instructor visits the same classroom for a short session twice a week for eight weeks. Before leaving at the end of each visit, the instructor gives a bit of mindfulness homework. At the next session, she invites the children to share their experience, asking, “How have you been using your mindfulness?”

When I first heard one of the instructors use the phrase “your mindfulness,” I was intrigued. Is it possible to awaken children’s interest in this practice by inviting them to claim mindfulness as a skill they are developing that is uniquely their own, almost like a secret power? It’s a very subtle and effective way of generating interest. Rather than introducing mindfulness as an area of learning and inquiry that is separate from them, this way of introducing mindfulness invites a sense of self-discovery.

At the art gallery we explored two ways of being mindful: deliberately bringing our attention to listening, seeing, or moving; and simply being mindful of what draws our attention. Developing this kind of receptive awareness demands certain conditions. It’s not easy to tune into one’s own experience when a lot is happening around us. Our attention is constantly being drawn elsewhere.

To encourage the children to discover their own unique ability to notice in this receptive way, I asked them to move from one gallery space to another without speaking, so they could pay attention to what they were observing and let their friends and classmates do their own noticing.

The children enthusiastically engaged in learning mindfulness through art.

Asking children for their thoughts

One discovery for me in delivering this program is the value of giving children many opportunities every day to share their experience, with questions that invite the development of self-awareness: “Why do you think you noticed that piece of pottery first?” “What do you like about the pink moose?” “Why do you think so many of us noticed the umbrellas hanging upside down?”

Children are noticing all the time, but rarely does an adult inquire into the world of their perception. When given the chance to share their experience, however, children gain confidence in their noticing skills.

Drawing and writing are ways to make the experience of noticing more tangible. In the budget for the program at the art gallery, when we applied for funding from the Victoria Foundation, I made a request for sufficient funds to give every child their own sketchbook. After we had practiced mindfulness through a number of different modes, we found ourselves in the ceramics exhibit. The children gathered on the carpet amidst about 30 pedestals supporting pottery bowls, platters, urns, and vases that caught the light. Tucked behind the bench where I sat was a large bin, well stocked with small sketchbooks.

Instead of just handing out the sketchbooks, I said, “We have a gift for you.” Next I paused. I asked them to notice how that announcement made them feel.

“Surprised,” said one girl.

“Grateful,” said another.

“Excited,” said a boy.

“Curious,” said his classmate.

One student admitted to feeling nervous. An unexpected gift might not be a good thing.

The children were universally delighted to receive a sketchbook of their very own. When they had claimed their sketchbooks, I asked them to draw a sequence of sounds. They were puzzled but willing to give it a try.

I had brought an instrument with me—a tuned metal drum called a hang. I carry it in large canvas pouch, inside a hard-shell plastic case.

Children trying to draw on paper the sounds of this metal drum.

With their pencils poised, the children listened as I unzipped the pouch. How does one draw the sound of unzipping? To give them an idea I made a kind of zigzag tune, unzipping and then zipping. Next I undid the velcro tabs along the sides of the plastic case. Velcro makes a distinctive sound, but how might one draw it?

When the drum emerged into view, I played a slowly descending scale. Though they were unsure how to represent sounds with a graphic image, they soon discovered many possibilities, including short sharp lines, curving lines, and prickly shapes.

From there we moved to story-listening. For more than 20 years I have been translating and performing the Jataka tales (stories of the Buddha’s former lives). As a Community Dharma Leader, I will often include a story in my teaching. In doing so, I’ve found myself intrigued by the way storytelling engages a certain kind of receptive listening, which offers opportunities for the development of empathy and self-awareness.

Recently I have begun asking children, when the story comes to an end, about the kinds of sensory perception they recall happening within the narrative. What sounds did the characters hear? What physical sensations did they experience? Were there moments when the characters’ hearts were beating fast? By their responses I learn over and over again, the power of story to engage a child’s imagination. Image by image, they are co-creating the story with me. This makes storytelling a remarkable vehicle for teaching mindfulness.

Learning the skill of mindfulness has tremendous benefits. When it is introduced in the context of a setting like an art gallery, seeds are planted for children’s growing confidence in their own unique perspective. Noticing what we notice is a path of self-discovery, leading onward to a deeper inquiry about who we want to be.

Margo McLoughlin is an educator, storyteller, and writer based in Victoria, British Columbia. She is a graduate of the Harvard Divinity School and the Community Dharma Leader training program at Spirit Rock. Margo leads non-residential retreats and gives classes on Vancouver Island. Currently her classes are offered online.