Pandemic Pushes Pilgrimage Pause Button

Written by: Len Bordeaux

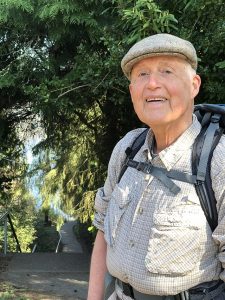

Len Bordeaux walked for many weeks around his neighborhood, with a loaded pack, to build strength for the pilgrimage.

Photos by: Len Bordeaux, Carson Furry, Rozenn Lemaitre

Just after New Year’s Day, nearly three weeks before the first reported incidence of coronavirus in Washington state, I conceived the idea of walking around the state to listen to people.

The purpose behind the 1,200-mile walk was to understand others’ values. A difference of opinion has now become a reason to see our neighbor as our enemy, and political rivals who used to compromise now view each other as existential threats.

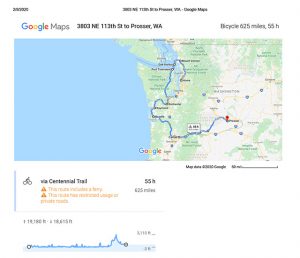

Bordeaux did a lot of route planning, including this map with the pilgrimage route in yellow.

Hatred between groups is dangerous and unnecessary, and my intention was to try to change that perception. I wanted to help.

Many people believe passionately in the benefit of ideas which to me seem harmful. Maybe I’m missing something. One thing I have learned is that holding tightly to views brings suffering. Over the course of my life I have been wrong so many times that it would be silly of me to take my views seriously.

“What,” I thought, “if I just go out, walk around and listen to people?” This could be an opportunity to learn and live way outside my comfort zone.

Repeatedly climbing 192 stairs was part of his training.

I planned to promote peace by being peaceful myself: listening to others, trying to understand their motivations, and making friends with folks who have different views. My plan was to walk along small roads, camping or enjoying offered hospitality, carrying a sign: “Pilgrimage to Listen.”

I have been devoted to the teachings of the Buddha for over 20 years, so how might I apply the Dhamma toward healing divisiveness in our society? When I first read about the tudong walks of Buddhist monks (long, solitary and austere wilderness treks), something in me resonated. To walk the talk … to be in the world with all its dangers, pleasures and challenges, and offer everything I have for the relief of suffering … what could be a better way to live?

Pilgrimage to Listen was born from this reflection. Though the walk would be challenging, I believed that I could do it this year, commemorating my 74th birthday on the road. Next year, who knows?

Bordeaux was strongly supported by the Seattle Friends of the Dhamma group.

I wasn’t a very good candidate for a tudong walk. I love day hikes and the occasional short backpacking trip, but my secret has been that even when I was thrilling to the views along a ridge in the Glacier Peak Wilderness, part of me was relishing getting back to a cozy room and a cup of tea.

After the initial glow of excitement, preparing for the trip became a lot of work. As I made long to-do lists, bought maps to plan my route, ordered a weatherproof “Pilgrimage to Listen” sign to display on my pack, set up auto-pay for my bills, I was tempted to tell friends I had no idea how complicated the logistics for this trip would become. But that was not true. I did have an idea; it was just woefully inadequate.

In early January I sat down to calculate what I would have to do to train for my planned April 18 start date. I needed to transition from my sedentary work as an insurance agent to walking the 72 miles per week, carrying 45 pounds, that I would need to average on the pilgrimage.

Bordeaux’s practice-walking packs included barbells and water bottles for weight.

Practice-walking was my (sometimes nagging) companion throughout my preparations. At first I walked a 4-mile loop around the neighborhood daily (including a 192-step stairway). After a few weeks I was walking three to four hours, six days a week, carrying 30 pounds while my chronically-sore back worried and complained.

My remaining waking hours were spent emailing Buddhist and Quaker groups along my route in hopes of lining up places where I might camp overnight, and making dozens of other preparations.

My business partner was supportive, and friends and strangers leapt in to help. One friend “loaned” me her backpack and a lightweight backpacking tent; another sewed a “rain apron” to keep my legs dry without creating condensation. Another friend loaned me a 25-pound barbell weight to augment my training pack.

A Google map of just a third of Len’s route, including crossing the Cascade Mountains.

Other friends sat with me in my apartment piled high with gear including packs, boots, and camp stove, spending hours advising me how best to update my old backpacking equipment while donating high-tech, lightly-used clothing to the project.

After practice-walking around the neighborhood, it became obvious that my new boots required more stretching around the ankles. The owners of the cobbler shop were enthused when I told them about my pilgrimage, and referred me to a cousin in Tonasket who invited me to stay on the way. So before even beginning the pilgrimage, I had experienced wonderful kindness and generosity.

Then on March 19, a month before I had planned to start walking, I cancelled Pilgrimage to Listen. The increasing spread of COVID-19 and calls by public officials to limit unnecessary travel and contacts made it irresponsible to continue. The motivation for the walk was to hear clarification of the values held by others and to encourage tolerance and acceptance, but in an environment of fear and genuine threat, it seemed unlikely I could have those conversations.

Assembled gear for the pilgrimage (minus food and water) ready to pack.

I stopped doing my training walks when it became clear that I could not do the pilgrimage as planned. This was accompanied by relief at not having to strap on a heavy pack for practice walks and also regret over watching my newly-acquired stamina vanish.

My body hurt. My back was strained, my ankles were sore, and my waist was grated raw by the pack waistband. Part of me was glad that I now had an honorable way out. And along with that feeling of relief came the sad old inner critic: “Of course! You would never actually do anything like this. You just dream the impossible dreams, then go back to sleep.” There was also guilt over letting down people who had helped and believed in me.

A few weeks later I developed a painful strain in my hip and lower back; painful enough to preclude even short walks and to interfere with sleep. Whether this was the result of overly ambitious training or of quitting the training too quickly and reverting to deskwork I don’t know, but having back pains amid a pandemic is not the way to begin a pilgrimage.

The trip may be cancelled, but Bordeaux continues his practice.

Yet, these things will pass. Already the back pain has eased, though my training-walks are back to square one. My motivation and enthusiasm continue.

Now I’m leading a quiet life. My work has slowed because of COVID-19, so as I begin morning meditations I can dispense with setting the mental alarm that got me off the cushion and to my desk on time. After finally cancelling the pilgrimage, I see how much anxiety had built up around just contemplating the cancellation: Could I get back in shape for a shorter version this summer? What if I’m unable to do it next year, or ever? All my effort and expense would have been lost; to say nothing of my credibility and self-image.

Now, breathing quietly, I can let go of all that. Breathing in, maybe I will walk. Breathing out, maybe not. Breathing in. Breathing out. A smile spreads from deep inside.

Len Bordeaux has been studying and practicing Buddhism in the Theravada tradition for over 20 years. His primary teachers have been Bhante Henepola Gunaratana, Rodney Smith, and Ajahn Sona, though he is fortunate to have received instruction from many others. He lives in Seattle.