Ven. Pannavati Includes All In Her Kindness

Written by: Denis Martynowych

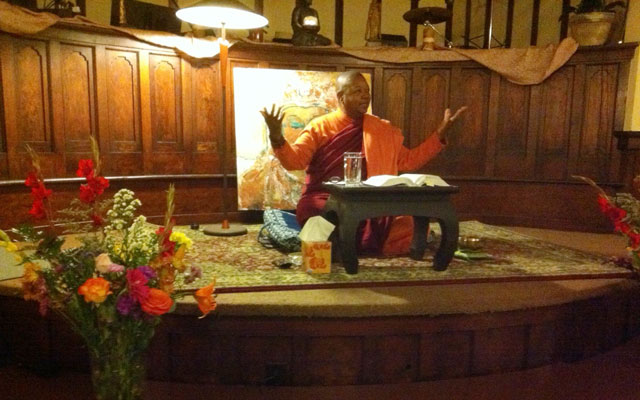

Venerable Pannavati teaching on stage, at the Tacoma Center for Spiritual Living.

Photos by: Denis Martynowych in Tacoma, unknown in India and North Carolina

“It is not enough to sit on our zafus. These times call for compassionate action to be an integral part of our practice,” says Venerable Pannavati.

Venerable Pannavati touched on this theme in many different ways during a recent teaching tour of the Pacific Northwest. Like Mahatma Gandhi, who famously said, “My life is my message,” her teachings are all the more powerful because she personally expresses the Bodhisattvas’ commitment to help end the suffering of others.

Venerable Pannavati is one of the first African-American Theravada nuns in the United States, and co-abbot of Embracing Simplicity Hermitage, a Buddhist practice center in Hendersonville, N.C. She is ordained in the Chan school of Mahayana Buddhism, has received Zen transmission from Roshi Bernie Glassman of Zen Peacemakers, and is a vajrayana practitioner as well.

Venerable Pannavati reaches out to an “untouchable” child outside Tamil-Nadu, India, in December, 2011.

Her insight is rich with warmth, compassion, wit and humor. She is known for her ordination of Thai and Cambodian nuns, work with homeless youth in Appalachia, and ministry to the “untouchables” in India, many of whom have become Buddhist practitioners.

During her recent tour, Pannavati gave dharma talks in Seattle, Tacoma and Portland, as well as traveling to Canada to give talks in Victoria, and on Salt Spring Island, both in British Columbia.

In Seattle, she took time to be with a dozen homeless teens, and treated them to lunch. One teen spread his jacket on the ground so she could be more comfortable, sitting with them on the sidewalk at 2nd and Pike, surrounded by downtown Seattle traffic.

There on the corner she listened to their stories, acknowledged their struggles, and gently reminded them of their goodness, their Buddha nature. She was equally gracious when she reassured a security guard, whose job it was to enforce anti-loitering laws targeting the homeless, that we would be leaving after the meal. When it was time to say goodbye, the teens all gave her long hugs.

Venerable Pannavati’s kindness attracts the Indian children around her.

After that meeting Pannavati invited one teen to come to Hendersonville, and join the program she founded that helps homeless teens get off the streets and build their life and job skills. When asked her why she made the offer to that particular teen, she said that she sensed he was ready to make a significant change in his life, adding that moving to a new place would lessen the pull of old habits and support his intention.

Venerable Pannavati said she endeavors to trust her inner voice, which can sense when someone is ready to open to another level of their unfolding. Like the Buddha, who offered his teachings to everyone from kings and beggars, Pannavati endeavors to meet each human being with an open heart, right where they are.

In the talk she gave at Seattle’s Keystone Church on Nov. 9, she shared her direct experience with racism as a 13-year-old girl, visiting her aunt in North Carolina in the 1960s.

On the first night of her arrival a group from the Ku Klux Klan knocked on her aunt’s door, demanding to know why the young Pannavati had not stepped off the sidewalk when a white woman passed her near the train station. Her aunt pleaded that since it was her first time visiting the young Pannavati (then called Diane) was unfamiliar with local customs. However, the KKK group would not leave until her aunt spanked Pannavati in front of them. Pannavati decided to take the next rain home to Washington, D.C., with the intention of never returning.

Venerable Pannavati at Embracing Simplicity Hermitage, North Carolina, June, 2012.

But about 40 years later Pannavati did return to settle in rural North Carolina, now as a Buddhist nun. To become accepted into the local community she needed to overcome what she described as four strikes against her: being Buddhist in a predominantly Christian community, black in a largely white community, female where women are not encouraged to be leaders, and outspoken where Southern tradition emphasizes genteel qualities.

Her practice and training, as a Christian minister and now a Buddhist monastic with a doctorate in religious studies, have served Pannavati well in building bridges across these major cultural divides. For example, when three women from the local church came to her hermitage to express their concerns about a Buddhist offering services to their homeless teens, Venerable Pannavati was able to hold them in compassion and to quote from the Bible. By the time they finished their meeting, the women had offered to collect household items from their congregations for an upcoming rummage sale, to support Pannavati’s teen programs.

Venerable Pannavati now has many dharma students In Hendersonville, and supporters for her community service projects. She believes she has changed Hendersonville for the better, and said, “Regardless of what happens to me, it will be a more open and welcoming place for anyone.”

Venerable Pannavati and Tacoma teacher Jude Rozhen share a moment in Tacoma.

Venerable Pannavati’s work with Dalit people in India, also called untouchables, echoes this same theme: helping protect people from discrimination, while supporting their inner aspirations.

She started this work after several large communities of Dalits asked her to come and teach them Buddhism. Many of these people, on the bottom rungs of the Indian caste system, have been converting to Buddhism in recent years as an expression of religious freedom. They sought her out because they felt an African-American Buddhist teacher would better understand what it means to be discriminated against, and how to best use the teaching of the Buddha to help overcome the internal and external suffering of racism.

Despite all of her other responsibilities she felt could not refuse their request, and began making regular trips to India, despite the danger of the work.

In some areas of India, Dalits who stand up to the oppression are killed with impunity. Yet her compassion for their situation, and the possibility of supporting their liberation, has overcome obstacles that arise for her and others who work with her.

In 2011 she “adopted” 10 Dalit villages in India, encompassing 30,000 people, and committed to help them establish an “egalitarian community” by providing education and micro-loans to women, according to her website.

In her dharma talks, and in the ways she engages with the world, Venerable Pannavati teaches that each of us can change ourselves and benefit society the most deeply if we are not concerned about who gets the credit. This is a practical yet profound way of expressing the Buddha’s teaching of non-self.

The more we embody our true interdependence with each other, the more access we have to our Buddha nature. The goodness and power of our true nature is immense. One gets a sense of that from being around Venerable Pannavati, and how she lives the dharma.