A Year of Living Peacefully: Ajahn Sona’s Upcoming Solitary Retreat

Written by: Dilani Hippola

Photos by: Dilani Hippola

The primary Birken Forest Monastery building, at sunrise.

After almost 25 years of monastic life, Ajahn Sona, abbot of Birken Forest Monastery (Sitavana) in British Columbia, Canada, will be taking a step back from his duties to devote a full year to solitary retreat at the monastery.

He is to start his retreat in April, 2013, and end the following April. Venerable Sona will conduct his retreat in his small cabin, called a “kuti” in Theravada tradition.

During his retreat he will maintain silence, forsake contact with the outside world, and use no electronic gadgets.

The following interview was conducted by one of Birken’s resident stewards. The monastery is in the Thai western forest tradition, and is located in the secluded forests of British Columbia’s interior.

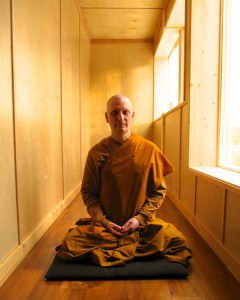

Ajahn Sona seated in the new enclosed walking meditation path in his kuti.

Interviewer: Ajahn Sona, many of your supporters are very pleased to hear that you will soon be taking a full year of solitary retreat. Can you tell us what motivated you to decide to take this retreat?

Ajahn Sona: The idea of a senior monk spending extended periods of time in seclusion is a fairly common idea in the forest meditation tradition of the Theravada school and goes back to the time of the Buddha. Abbots and senior monks in the West often spend many years establishing new monasteries, training new monastics and spreading the dhamma across vast terrains. This is a fairly demanding task involving much planning, building, teaching and travelling. So, from time to time, it’s thought to be a good idea to take a year of pure meditation – to honor our true monastic vocation.

Even after his enlightenment, the Buddha often went into retreat, one time for three to four months. It’s very interesting. People wonder: Why would the Buddha have to meditate if he’s fully enlightened? This is something very important for people to understand. The fully enlightened monks of the time of the Buddha continued to practice deeply and, very importantly, continued to enter into deep states of concentration called the jhanas.

It is crucial to understand this here in the West, where practitioners are frequently introduced to Buddhism through vipassana schools where there is no emphasis on jhana or deep samadhi. We should refer to the historical facts to see that the fully enlightened monks of the Buddha’s time continued to enter into these deep states, and appreciated long periods of time in seclusion even after their enlightenment.

Although I’m not comparing myself to the fully enlightened monks at the time of the Buddha, even more so should a monk of this time carve out periods of time where there are no teaching or administrative duties and where he can cultivate the deeper stillness practices of samadhi. This is more or less my job. If I did not do this, I would be somewhat negligent as a monk.

In Thailand, where there are some 35,000 monasteries, abbots and senior monks often leave their own monasteries for such retreats and go off to other related branch monasteries where their solitude can be supported and where they are secluded from the practical demands of their own communities. In North America, where there are still only a handful of branch monasteries, this isn’t so easy to do. It also occurred to me that there’s really no need to leave my own monastery. Over the last 11 years, we have established a very pleasant environment and structure here at Birken, and I truly find it my favorite place to be. So I will spend my year of retreat right here, in my own monastery.

Ajahn Sona’s kuti, where he will spend a year in solitude.

Interviewer: Ajahn, as the abbot of this monastery, you play the most central role in the running of its day-to-day affairs, not to mention the extensive dhamma teachings that you provide on a regular basis both here and in other locales. How do you plan to safeguard your seclusion during your retreat?

Ajahn Sona: My first focus has been to ensure that I have an appropriate dwelling place for the retreat. A monk’s dwelling in the Theravada tradition is a called a ‘kuti,” a small cabin of limited size. My kuti looks over a marsh and bird sanctuary; it is a very austere but pleasant and peaceful scene. We have recently had the kuti modified for the Canadian geography and climate by adding a fully enclosed, heated walking path so that I will be able to practice walking meditation in seclusion. The kuti has been designed to be maximally solar efficient and highly insulated, so that it will basically be running on natural energy. At Birken, we’re very conscious of the green movement and the problem of global warming. I’ve spoken extensively on green monasticism and my retreat will be a model of living as simply and as harmoniously with nature as possible.

During the retreat, I shall keep a very restricted profile. I will not be conversing with anyone during this time and I will collect my daily meals privately and silently in a sort of alms-round fashion. The two wings of the Buddhist monk are his robes and his alms bowl and, by these means, he flies around the world. So, with these two wings, I will fly over to the main building each day, silently collect my meals and then return to my kuti to eat.

I shall not have any communication through email or phones, and I will not have any media or technological gadgets in my kuti. My sole focus will be meditation and I will leave all practical affairs and teaching duties in the hands of other monastics and lay stewards. The monastery will remain open, but it will be a very quiet year with few activities and limited visitors.

The primary meditation hall, inside the main building at Birken.

Interviewer: Many people may wonder what exactly you will be doing in your kuti during your retreat. How will you spend your time, Ajahn?

Ajahn Sona: When the Buddha went into retreat, he said to his attendant, Ananda, “People may ask what I am doing in my three-month retreat. You may tell them, Ananda, that I am watching my breath.” It’s very interesting that the Buddha continued to practice breath meditation. So I will certainly try to pattern myself after the Buddha and spend a good deal of my time in my seclusion watching my breath. I will also make good use of the new enclosed walking meditation path in my kuti. Since the time of the Buddha, it has been considered important for monks to practice both sitting and walking meditation in order to maintain the health and balance of their practice. If one is living exclusively as a contemplative monk, one needs to move the body around as well. We do this by simply walking back and forth in a limited space of 30 or 40 feet. It is very refreshing to the body and fosters a different quality of mind than that of sitters’ practice.

I will also probably have some volumes of the Pali Canon in my kuti, and will carefully and enjoyably read a few suttas per day. Although I have read most of the main teachings of the Buddha, it’s always good to go over them again, to allow them to percolate and to see what comes up spontaneously in stillness when one encounters the words of the Buddha. In short, I will live a very simple life devoted to deep meditation in silence and solitude.

Buddha statue on the marsh.

Interviewer: Ajahn Sona, you have been an inexhaustible fountain of wisdom and loving kindness for so many practitioners over the years. Do you have any words of advice for the many disciples who will miss your wise teachings and compassionate support during the period of your retreat?

Ajahn Sona: I think it’s time in North America that the lay sangha comes to appreciate that the idea of a monk is not to be busy or to be in a business transaction with people: you teach, I pay; you travel and I’ll support you. It’s not this kind of reciprocal idea. We must move beyond that to an absolutely freely supported transaction where monks and nuns who are serious about pure contemplation are supported because that, in and of itself, is a beneficial thing. This is a central aspect of the basic teachings of the Buddha.

Somehow I hope that my students, and even those who read this article, will benefit from the mere idea that somebody is in peaceful seclusion for a year. Somehow I hope that you can keep this image in your mind and even visit me in your mind as I sit peacefully and quietly in my kuti. Somehow I hope that the image of one who is peaceful, who is devoting day and night to the cultivation of deep stillness, can come to your aid in the middle of a frantic day.

That’s one of the reasons for contributing this article. By this means, others who come to know about my retreat can participate simply by bringing this image to mind. This is the value of this pure contemplative retreat.

About Ajahn Sona:

Ajahn Sona’s encounter with Buddhist teachings as a young man initiated a spiritual journey, which led him to renounce his worldly life as a classical musician to become a lay hermit for several years. In 1988, he ordained as a Theravada monk under Ven. Bhante Gunaratana at the Bhavana Society in West Virginia, and began his training. He trained and practiced for more than three years at Ajahn Chah’s forest monasteries in northeastern Thailand, particularly Wat Pah Nanachat.

Upon his return to his country of birth in 1994, Ajahn Sona founded the first “Birken Forest Monastery,” a primitive shack monastery near Pemberton, B.C. As the community of monastics and visiting lay practitioners grew, the monastery moved several times until arriving at its current location, near Kamloops, B.C., in 2001.