University of Oregon Neuroscientist Brings New

Understanding of Meditation, Brain versus Mind

Written by: Steve Wilhelm

Marjorie Woollacott teaches an Osher Life-Long Learning Institute class entitled “Integrating Scientific and Spiritual Perspectives on Human Consciousness.”

Photos by: Paul Hawkwood, Rowman and Littlefield Publishing Co., Anne Shumway-Cook

A longtime neuroscience professor at the University of Oregon, Marjorie Woollacott, has been exploring the distinction between mind and brain, and in the process shedding new light on Buddhist practice and understanding.

Now a professor emeritus from the university, Woollacott continues active research in academia, and is just publishing her third book.

Her work has also brought her into less-traditional arenas, and she also serves as president of the Academy for the Advancement of Post-Materialist Sciences, and director of research for the International Association of Near-Death Studies.

She also has an active meditation practice, which while not Buddhist is in the somewhat parallel tradition of Kashmir Shaivism. The following is an interview conducted in May, 2022:

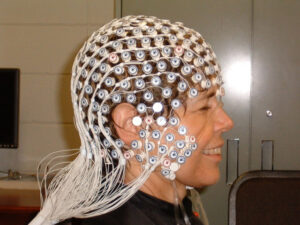

Her head wrapped in Electroencephalography (EEG) sensors, Woollacott is tested on the relative effects of meditation and exercise on attention focus.

You published or co-published five papers on meditation at University of Oregon in Eugene. What is your current activity there?

I’m still a member of Institute of Neuroscience at the University of Oregon, and I’m a professor emeritus of the Department of Human Physiology. I publish all my papers on meditation as a member of the Institute of Neuroscience.

We’re soon to publish “Spiritual Awakening: Scientists and Academics Describe Their Experiences.” This is a book of essays by 56 scientists and academics about their own spiritual awakenings, which in many cases they would not share with others, especially not with their fellow scientists and academics.

Woollacott teaches meditation to University of Oregon students, as part of a study measuring their EEG responses.

You do practice in a spiritual tradition of Kashmir Shaivism, which is an aspect of Hinduism. How did the openings you had in that tradition launch you into research into the nature of mind, and what year?

In 1976 my sister invited me to a meditation retreat by a meditation master in Kashmir Shaivism. In that retreat although I was a skeptical scientist, and had been doing science all my life, I decided I was going to be curious, and just open to see what happened.

The initiation was a touch from the swami. I experienced a current of electricity, like a mini-lightning bolt. I had an utter certainty about the event, and also an amazing certainty, in my heart, of an expansion outward of love and joy, almost like nectar.

Woollacott’s first book, “Infinite Awareness, the Awakening of a Scientific Mind,” traces her growing understanding of mind and brain.

Prior to that you considered yourself a “materialist,” and thought mind was exclusively a result of brain function. There must have been a gradual shift to your current viewpoint. How long did that take, and how was the process for you?

What began to happen in my meditation experiences was I felt these energy centers (e.g., the heart) in my body. What I started to understand is that the centers that meditators describe are in the subtle body, and they may interpenetrate the physical body, but have nothing to do with the heart, etc., per se.

Without ever reading about energy centers related to Tibetan Buddhism or Kashmir Shaivism, I began to feel them in my body. I wanted to know what’s going on in the subtle levels of body and mind, not just the physical levels of the brain.

For Woollacott her scientific and spiritual investigations are inseparable.

It sounds like you had an unlayering of understanding. Can you describe?

Slowly but surely I began to question my materialist perspective. What really did it for me was when I decided to turn my master’s thesis into a book, and that’s when I started writing “Infinite Awareness, the Awakening of a Scientific Mind.”

What happened was that while looking at the literature, to try to understand what the research says about the fundamental nature of consciousness, I began to read papers that I never would have looked at before.

For example I really looked carefully at near-death experiences. In the research literature there are carefully controlled studies, where they bring in all the people in hospitals who have cardiac arrests, and of those people who survived, about 12 percent of people have a “core” near-death experience, where they’re out of their body observing the resuscitation from above, even though their heart has stopped and their EEG (a measure of brain waves) is flat-lined.

I decided to write a chapter on cases suggestive of reincarnation, and of course neuroscientists do not believe in reincarnation. I looked at reports from 2,500 cases studied at the University of Virginia, and when I looked at the data I could not deny that this was a highly probable phenomenon.

Understanding better what’s happening in the brain during spiritual openings, brings Woollacott better understanding of the non-material mind.

How could you succinctly put your core understanding, of the relative roles of brain and mind in human beings?

Here’s the question that is so important for neurobiologists and spiritual seekers. The materialists simply say consciousness emerges from the activity of our brain, and when the brain stops functioning, consciousness ends.

But the research on near-death experiences says that when brain begins to shut down in an NDE, your consciousness becomes hyper-aware, as if it’s more aware than it’s been its entire life.

This is because, as we now know as neuroscientists, there are filters in the brain that filter out this vast awareness, which we can have access to during spiritual and mystical experiences.

Woollacott walking in nature during a 2008 teaching trip to Berlin.

We all know that our sense of reality is colored by our organs or gateways of sense contact. What does your research suggest about the role of brain, versus mind, for what comes in through the sense doors?

The thalamus and the executive attention system are filtering out everything other than what we need to attend to. This is happening all the time, even when we’re not aware of it, and we’re seeing only a portion of the reality around us.

This explains why we each have totally different stories of an event we experience together, because the brains, in each person, are attending to completely different things.

Our default mode network often causes our narrative in our brain to take over our entire awareness, with our stories we’re telling ourselves. We actually don’t see “reality” around us, because of these stories.

What’s going on when people do mindfulness practice, in terms of your research?

One of the main points of meditation is to quiet down those stories, in the default mode network, so we have this broader awareness.

The way I look at mindfulness is mind is now still, so I just focus on pure awareness of what’s going on around me. Therefore I’m not creating a story about what’s happening; I’m just there with it.

You’re talking about witnessing your mind, so you’re up there watching the thoughts without having them control you. The witnessing of the mind is where I’m no longer identifying with the thoughts, and that’s the key issue.

We forget who we ultimately are because we’re identified with our individual consciousness, and meditation’s whole point is helping us de-identify with the individual point of consciousness, and begin to understand we’re part of wider consciousness.

To what degree is mindfulness a brain function or a mind function?

I always think mindfulness starts out with intention, because consciousness is primary as a mind function.

It starts out as an intention to be in the present moment, and therefore be mindful. Then my intention, through the dorsal lateral pre-frontal cortex, a key area of the executive attention system, directs my brain to turn off the narrative or at least turn down the narrative, to be in the present moment. It’s sort of like my brain and mind cooperating.

During meditation people often experience what’s referred to as “monkey mind,” the unbridled arising and passing of a stream of thoughts and associations. What is happening when monkey mind is operating?

My default mode network, which they also call the mind-wandering network, is now in control. It’s basically just letting the midbrain-cortical loop of all of my stories throughout my lifetime go through my brain, and one or another is going to spontaneously come up at any given moment.

Of course we can also get them triggered by an event, and past memories. They are not true of what’s happening in the present moment…those are past memories. What we are reminded in all of our meditation traditions is we need to let go of the past, and we need to be in the present so we can see, for example, what a given person in front of us is now, rather than what they used to be 18 years ago.

What have you learned from research about the distinction between concentration meditation, shamatha, and mindfulness practice?

I helped with a study at U.C. Berkeley, and the researcher had two groups of meditators, one doing concentration meditation, and the other mindfulness mediation.

She showed that in terms of the attentional processing abilities, there was no difference between the two groups. My sense about why there wasn’t (and they were both much-better than non-meditators), is because in fact in most of our practice they are part of a continuum, even within a single session.

I may start focusing on breath, but I gradually move into a quiet stillness where I’m fully present. It’s very hard to do a study where you have only one or only the other.

In Buddhism the understanding of nibanna or nirvana is a bit of a paradox, because it’s simultaneously a state of ultimate not-clinging, a negative, and a radiant awakening to Buddha nature, or the ultimate nature of mind. What does your research suggest about what’s going on in awakening, how we can understand it?

There is an emptiness of our individual narrative of who we are, and the open awareness of this vastness, of who we truly are.

There’s a not-clinging, that is, a sense that I’m connected to everything, so there is nothing to cling to.

If you’re happy to flow with whatever is happening, you go with the flow. You’re happy with whatever comes next because it will ultimately be of benefit to you, and thus you are full of compassion and love.

Steve Wilhelm is editor of Northwest Dharma News. He has practiced in several Buddhist traditions since 1987. He currently leads Eastside Insight Meditation, and is a Local Dharma Leader for Seattle Insight Meditation Society. A former journalist, Wilhelm has edited four dharma books and is currently editing a fifth. He lives in Kirkland, Washington, with his wife Ellen.