The Dana Dilemma: Are Paid Teachings Buddhist?

Written by: Sarah Conover

Pacific Hermitage monks, here led by Ajahn Sudanto, sometimes walk through heavy snow.

Photos by: Friends of Cloud Mountain, JFOTO.com, Northwest Vipassana Center, Sravasti Abbey, Steve Wilhelm

Around the Northwest, dharma teachers and students are working to develop ethical and effective models for how to compensate teachers, and how to cover expenses of facilities that support those teachers.

Much of this effort pivots around 2022 interpretations of the word dana, the ancient Pali word for generosity. Institutions and teachers in the region are responding to the challenge along a spectrum, from more secular vantage points to faith-based ones, all with a goal of making dhamma teachings widely available

“Dana can be a bit of a sore point all around. I’ve heard monastics, lay teachers, and administrators of centers talk about how they try to balance the work that they do—offering teachings and programs—and pay for it all,” said Ajahn Sudanto, abbot of Pacific Hermitage in White Salmon, Washington. “It’s gone on for decades and there’s still a lot of handwringing. I find it kind of sad that we haven’t figured this out.”

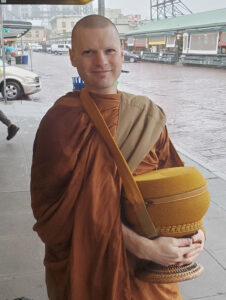

Nisabho Bhikkhu, co-founder of Clear Mountain Monastery, at alms rounds at Pike Place Market in Seattle.

Generosity is at the foundation of all Buddhist teachings. But ideas about what dana can be—a monetary transaction versus a field of virtue—reveal a range in understanding and practices as Buddhism has unfolded in the West. While various approaches have pros and cons, all must somehow harmonize with the Buddha’s understanding of radical generosity, even in a consumer culture.

This complex is hard to avoid, as retreats and other forums commodify Buddhist ideas. When the teachings become entangled with a capitalist transactional model, what’s at risk? Are we transmitting the breadth and depth of dana in the way the Buddha intended?

In the Beginning: Without Price

The dharma—what the Buddha taught—has been considered priceless across the millennia. At the time of the Buddha, monks and nuns, and sometimes laypeople. taught freely without expecting any compensation.

Even now monastics in more orthodox branches of Buddhism cannot ask for anything at all, (unless a donor has previously said to the monastic, “If you need this or that, let me know”). These monastics cannot even hint for anything but water, unless they are ill.

Ven. Thubten Chodron receives a child’s offering during an alms round with monastics from a temple in Jakarta, Indonesia.

While not all traditions hold to the vinaya monastic rules so strictly, the Buddha evolved monastic frugality for a reason: so monastics could offer teachings without strings attached. Because monks and nuns never receive more than necessities, there is less incentive to alter the teachings for material gain.

The underpinning of this paradigm was local laity providing basic requisites to monks and nuns. Other religious institutions provide for their own leaders in similar ways.

In the most conservative Buddhist denominations, monastics are forbidden to store food overnight because the Buddha intended they be dependent on, and available to, laity on a daily basis. This is the case with my own son, the Venerable Nisabho Bhikkhu of Clear Mountain Monastery, who is intending to develop a monastery in the greater Seattle area.

“Being a mendicant may seem impractical and risky,” said Nisabho Bhikkhu, who Monday through Friday appears with alms bowl at 7 a.m. at Seattle’s Pike Place Market. “Dana is a living relationship with radical trust in people’s goodness. Over millennia this trust has not been misplaced—the Buddhist monastic sangha is one of humanity’s oldest continuous institutions.”

Bringing the Dana Ideal to the West

Cloud Mountain Retreat Center has deeply depended on dana donations to develop infrastructure, like this porch.

A major flashpoint in the growth of Buddhism in the West, is the rise of lay (non-ordained) teachers. These are people who partly or totally earn their living by teaching the dharma, and there are now far more lay Buddhist teachers in the West than monastic teachers.

The Buddha spoke of teaching the dharma in a pure way, as one of the greatest acts of compassion for others. Yet the proliferation of lay teachers, with some form of monetary return, is new territory:

“I don’t know that it’s ever been really tried to transmit the dharma in this way, as a ‘profession,’” said Ajahn Sudanto.

The Buddha didn’t dismiss wealth as inherently bad; money itself is not the problem. But in much of the vinaya, the Buddhist monastic code, the Buddha sets a very high bar for the ethical integrity required for teaching.

“One should not teach with the wish to inspire listeners so that they make offerings to oneself,” the Buddha said in a discourse known as “Like the Moon” (SN 16.3). Even if the Buddha intended the warning for monastics, it could apply to anyone teaching the dharma.

Northwest Vipassana Center is expanding its retreat center in Onalaska, Washington, funded largely by donations.

The “dana talk,” asking for donations for a teacher after a talk or retreat, has become the norm. The talk is sometimes given by a lay practitioner, not the teacher, so the teacher isn’t personally requesting their own support.

But even so, when the talk is given students are vulnerable, and the experience can easily dampen the closing tenor of a retreat. Teachers often say that when they return to a room full of retreatants after a dana talk, those radiant faces have fallen.

Ven. Thubten Chodron, abbess and founder of Sravasti Abbey, in Newport, Washington, understands that lay teachers are in a difficult position.

“If I look at it from their point of view: ‘I’ve given up my career and my profession because I want to dedicate my life to the dharma, but I still have all the expenses of a householder—spouse, kids, mortgage, car insurance, life insurance, health insurance.’ Lay teachers are really in a bind,” Chodron said.

She adds that in many ways monastics are freer to teach than lay teachers, because they can accept requests to teach without thinking about how much dana they will receive, and because their needs are minimal.

Pricey and Priceless

Teacher Gil Fronsdal, founder of Insight Retreat Center, has been able to support the center entirely on dana offerings.

The high cost of operating residential retreats is another flashpoint, one that amplifies monetary and racial inequity in a society rife with social injustice. If retreats requiring catering, accommodations, and swaths of time off from work are at the heart of Buddhist practice, those retreats may prove inaccessible for many. Price is a key issue, and sticker shock can arise from opening catalogues from many Buddhist retreat centers.

Buddhist lay organizations are diligently trying to bridge this financial gap with scholarships and sliding scales, and many retreat centers won’t turn people away for lack of funds. They also are trying to keep costs low, and Cloud Mountain Retreat Center, located between Seattle and Portland, keeps sliding-scale nightly costs below $100.

In addition, many retreat centers offer to exchange room and board for work. But the fact remains that building and operating retreat facilities is expensive, and even renting a retreat facility can risk a group being left with significant debt.

In addition, generally none of the retreat fees support teachers. Centers instead count on retreatants offering dana directly to the teachers.

Buddhist monasteries offer a significant exception to this model, the world over allowing visitors to stay free, although a dana donation is welcomed. Keeping the monastic schedule of practice, work, and eating secludes a practitioner from their normal life, much like a retreat.

Sarah Conover offers time as dana, digging trench for electric conduit on Cascade Hermitage property.

Another regional option for non-fee retreats is the Northwest Vipassana Center in Onalaska, Washington, which offers teachings of the late Burmese teacher S. N. Goenka.

Although retreatants are asked to donate to the organization, it’s not a requirement. The center is staffed by volunteers, and teachers gift their time. Thousands of practitioners credit a Goenka course for introducing them to Buddhist meditation.

The Field of Experimentation

The Western Buddhist world at this point has thus evolved three models for paying for practice:

- The all-dana model, with everything freely given

- The fee model, just a single fee for teachings and retreat accommodations

- The hybrid model, where a fee is charged for direct costs, but dana is requested for the teachers, and sometimes as a supplement for the salaries of cooks and staff.

Ven. Chodron offers specially blessed Tibetan medicine pills to visiting sangha in Singapore.

Many students say the hybrid model should be renamed and not called dana, because those students often feel guilty in the way this is presented. Will it be their fault if the cook can’t afford health insurance, or if the teacher has to skimp on groceries?

But the down side of paying a set price is that a consumer mentality enters the situation. Now the dharma teacher is more likely to be judged by those paying the fee, and the product, in this case the teachings, needs to meet those expectations.

Gil Fronsdal, the co-teacher of Insight Meditation Center in Redwood City, California, is one of the few lay teachers in the U.S. who leads a dharma center, as well as residential retreat facility, supported completely by dana. Fronsdal is clear that he doesn’t view IMC’s all-dana arrangement in opposition to other models.

“There’s a wisdom in charging,” he said. “A fee allows people to be financially supported in a dignified way if it’s done well. There’s wisdom in paying. It’s a higher bar for deciding whether to commit to sitting a retreat.”

The Joy of Freedom from Transactions

The Buddha’s teachings tell us that generosity offers something profoundly valuable to the human experience. Generosity inspires people to follow the whole of the noble eightfold path, and to serve in the service of spirit over commerce. The Buddha didn’t just talk about death and suffering. He also spoke about many kinds of joy, especially the joy experienced before, during, and after an act of generosity.

“We don’t have a model of an economy of generosity in this country,” said Ven. Thubten Chodron. “I think of an economy of generosity as people contributing to each other’s welfare and to the welfare of the whole society. What we’re talking about is increasing our joy in giving.”

Gladdening the mind is just as necessary and urgent as are the more sober disciplines of practice. Dana is the very first paramita, or perfection, in nearly all Buddhist traditions. It isn’t a sideline practice, but a crucial foundation of the eightfold path.

The Buddha enjoined us to give “wherever the mind feels inspired.” This generosity can include monetary support, our time and labor, the gift of sila or ethical conduct (which makes us reliable and trustworthy), or the gift of noble silence.

Generosity in its fullest sense reveals essential truths that transactions can obscure. Perhaps to give is to find happiness, realizing that one’s isolated joy is small compared to shared joy. Anatta, not-self, is only empty of the individual, not of relationship.

Let us hope that as understanding of generosity evolves, dollar signs will no longer be a first thought for many, when they hear the word “dana.”

“Everything is dana,“ said Ajahn Sucitto, a senior monk in the Thai forest tradition. “We’ve been given birth. We’ve been given bodies. We are in a universe of dana and we participate in that. Dana is not a donation.”

Sarah Conover is a Theravada practitioner of 30-plus years, a feature writer for “Tricycle Magazine,” and co-steward (along with her husband) of Cascade Hermitage. This soon-to-be refuge in Winthrop, Washington, will support monastics and dedicated practitioners on solo retreat.