Celebrating the Dharma Life of Sanje Elliott

Portland Tibetan Calligrapher, Thangka Painter

Written by: Jef Gunn

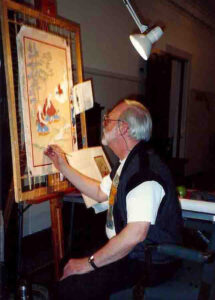

Sanje Elliott painting in his studio.

Photos by: Roger Edwards, Jef Gunn, Jacqueline Mandell

Frank Sanje Elliott, a master painter of Tibetan thangkas and a master Tibetan calligrapher, has died. He was 89.

Sanje Elliott leaves behind an enormous body of work that will support the dharma far into the future. He died peacefully in his Portland home on March 4, 2022.

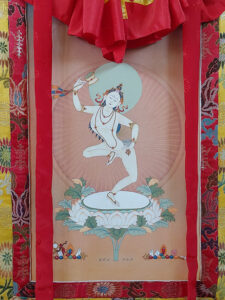

Sanje is perhaps best known as a master painter of Tibetan thangkas. These are the precise and colorful renderings of Buddhist meditational deities, on cloth, which Tibetans use to support visualization in vajrayana practice.

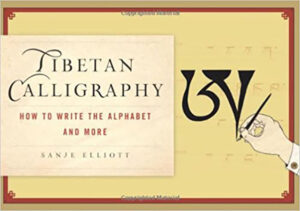

He was also accomplished as a Tibetan calligrapher, and in 2014 his book “Tibetan Calligraphy” was published.

Sanje painting during the Tibet exhibition at the Portland Art Museum, 1993.

This book shows clearly how to form the letters of the Tibetan alphabet, using a flat-edged pen to make the thick and thin lines. In practice, the act of making such fine forms with care is a meditation in itself.

Sanje also has been an important figure in Portland dharma circles, helping to found Kagyu Changchub Choling (KCC), in the mid-1970s.

Sanje began studying thangka painting in 1972 at Rumtek Monastery in Darjeeling, India, where he also studied Tibetan language and calligraphy. Upon returning to the U.S. in 1974 he continued training in thangka painting, studying with the late Glen Eddy for about 10 years.

How did Sanje come to this path and this way of working? Born in 1933 in Centralia, Washington, he grew up in Portland, Oregon. His mother taught art and music, and Elliott found ready support for his natural talents.

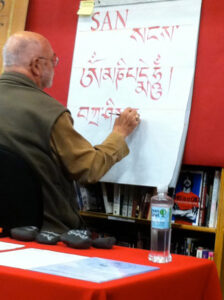

Demonstrating the Tibetan alphabet during a 2012 booksigning for “Tibetan Calligrapy,” at Portland’s Powell’s Book.

His parents both passed away at the end of his high school years, his father from alcoholism and his mother from multiple sclerosis. Sanje, and his older sister Pat, had to chart their own path for themselves.

Throughout Sanje’s life, tremendous creativity flowed through him like water, like light. Of course there’s always effort, but with Sanje it didn’t seem like effort. By all accounts he lived and breathed creative engagement.

Sanje created visually as a graphic artist, fine art painter, calligrapher, and iconographer. As a musician he played piano, saxophone, clarinet, and flute, and sang with a beautiful baritone voice.

Throughout his long life Sanje supported himself with his music, through his many small jazz bands and solo piano gigs. In addition, he supported himself with his graphic design skills, which he honed in classes at Grant High School and Lewis and Clark College, both in Portland.

The cover of Sanje’s book on Tibetan Calligraphy.

In Sanje’s senior year of college, a history of religion class got him questioning Christianity, as well as his plans to become a successful and wealthy commercial artist.

One night he wandered in the forested campus of Lewis and Clark College, asking himself “Why am I here? What is my purpose?” An inner voice responded, “Give.”

He promptly switched his major from graphic arts to fine arts. After graduation he left for Italy. Living the bohemian life in Florence he painted, and led a jazz band called “The Happy Boys.”

During these years in the middle ‘50s, he often visited the villa of art historian Bernard Berenson to read, and to study the Renaissance artworks there.

In his modern art, like “Spring turns the Wheel,” Sanje was influenced by European painters.

After one of these days of study, stopped at a stoplight in a village on his way home, Sanje experienced an epiphany of the interconnectedness of all beings. The next phases of his life can be understood as flowing from this moment.

Around 1958 he traveled to Munich, where he lived for a couple of years with some Australian artists. During this time Sanje was closely studying early 20th century modernist artists like Paul Klee and Piet Mondrian.

In a 2019 interview, Sanje said, “Paul Klee was important because he sort of held my hand as I walked across the bridge from realism to modernism, which was a very important bridge to cross if you’re an artist.”

Later he studied briefly with artist Oskar Kokoschka in Austria, and you can see the influence in his work for years after. Not so much line, but form, space and atmosphere take shape through broad, thick knife-loads of warm and cool color.

A thangka of Machig Labdron, originator of the chod lineage of Tibetan practice.

From 1961 through 1963 he lived in Australia, continuing to paint while leading another jazz band. The artwork of aboriginal Australians deeply influenced his work; now color gives way to pattern and rhythm.

In 1963 he stopped in Kyoto, Japan, on his way home to Portland. At the Daitoku-ji temple in Kyoto another direct experience opened his way. He was told to spend 30 minutes contemplating the garden.

“I sat there and believe it or not, the Zen garden got to me, and I got the message,” he said. “It was a symbol for the whole universe.”

This epiphany opened new directions in his life and his artwork. What I see, as an artist myself and as an old friend, is an integration of the patterning he borrowed from the aboriginal people of Australia, open color and form from Klee and Kokoschka, and light and stillness from Zen.

A thangka of the Tibetan Yidam of compassion, Chenrezig, painted by Sanje in 1976.

He was using ink wash and brush on paper, and later on his new forms integrated with the open color he’d been learning. The result was a full-body full-spirit expression of wholeness and movement.

In 1967 Sanje had a huge interactive artwork installed at the Portland Art Museum. Called “20th Century American Exorcism,” or “Trying to Fly,” it caused quite a stir with the public.

During this period Sanje began meditating, first with the Hindu Vedanta Society. Later he joined a weeklong Zen sesshin with Joshu Sasaki Roshi, which Sanje later called “brutal. ” But on the third day he entered a blissful state, and subsequently his studio work began reaching for symbolic representations of the teachings of Zen and of tantric dharma.

Around then Sanje read a translation of “A Jewel Ornament of Liberation,” by the 12th century Tibetan teacher Gampopa. He decided to find a teacher in the lineage of Milarepa, Gampopa’s teacher.

Sanje was known for his warm smile and laugh.

Sanje bought an around-the-world airplane ticket, and while in Morocco he sensed an inner light in the direction of England. When he arrived in London, someone directed him to Samye Ling Monastery in Scotland, where he took refuge and bodhisattva vows from the late Kagyu master Kalu Rinpoche.

Sanje then traveled through Europe, the Middle East and to Darjeeling, where he also studied Tibetan language and calligraphy. In 1973 , he returned to the U.S. West Coast via Nepal, Thailand, Indonesia, Australia, Taiwan and Japan.

In 1986 Sanje began teaching at Naropa Institute outside Boulder, Colorado. He also returned to Italy with his partner, David Busse. His artwork from this period is loose, lighthearted and colorful, reminiscent of Cézanne’s landscapes. He’s clearly happy.

During this entire period, all these years of travel and teaching, of Kagyu centers and Zen centers and connecting with people, Sanje continued playing music, creating art, and smiling that great big heart-warming smile. You couldn’t help but smile back.

Living of course also brings disappointment, melancholy, longing. I’m saddened by Sanje’s passing. The more I look into my friend’s story, the more I want to spend time with him again, to ask him questions. Yet his example always was to meet sadness with joy and beauty. This is how he taught us to give.

I share with you a recording of Elliott’s great laugh.

Jef Gunn is a Portland painter and printmaker, and a member of Kagyu Changchub Choling since 1998. Gunn and Sanje Elliott have been artist buddies since around that time.

In 2017 Gunn and Sanje collaborated on a joint showing of their art at the ArtReach Gallery in the First Congregational Church in Portland. Gunn teaches painting in Portland. See www.jefgunn.com for more information on his work, his shows and his classes.