The Legacy of Venerable Thich Nhat Hanh

In the Pacific Northwest, Alaska, Canada

Written by: Valerie Grigg Devis

Jeanie Seward-Magee of British Columbia, in 2012 receiving the Lamp of Wisdom from Thich Nhat Hanh in Plum Village, France.

Photos by: Rowan Conrad, Valerie Grigg Devis, Plum Village Press photos, Laura Jamieson Silverton, Joe Spaeder, Wake Up USA

Thich Nhat Hanh, the pivotal Vietnamese Buddhist master who died earlier this year, greatly influenced Buddhist practitioners throughout the Pacific Northwest, Alaska, and Western Canada.

By the time Thich Nhat Hanh died in Vietnam, on Jan. 22, 2022, he and his teachings had led to the formation of more than 40 Plum Village Sanghas in this region of North America.

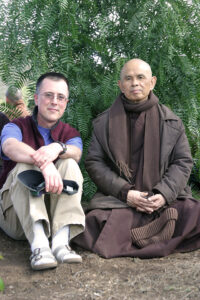

Jon Prescott from Guemes Island, Washington, sitting with Thich Nhat Hanh at Deer Park Monastery, San Diego.

Known by his students as Thay (“teacher” in Vietnamese), Thich Nhat Hanh remains one of the most deeply loved Zen masters by Buddhists and non-Buddhists around the world. His teachings continue very much alive today, and I spoke with 11 regional sangha leaders to gather their perspectives on his life and legacy.

ZEN LINEAGE

Thay lived his final years at Tu Hieu Temple in Vietnam, which he had first entered as a novice and where, in 1966, he received the “lamp transmission” from Master Chan That. Through that transmission Thay became a dharma teacher of the Lieu Quan Zen lineage. This placed him in the 42nd generation of the Lam Te Dhyana school, called Linji Chan in Chinese, and Rinzai Zen in Japanese.

Asked how Thay expressed his Zen practice, Jeanie Seward-Magee, of the Mindfulness Practice Community of British Columbia, said, “When you watched him walk, he was only walking. That was his Zen.”

The Most Venerable Thich Nhat Hanh, 42nd dharma heir of Chinese Zen master Linji, and founder of the Plum Village tradition.

Jonathan Prescott, teacher of Anacortes Mindfulness Community in Washington state, said, “History will regard Thay as the Dogen of this era. Dogen brought Zen from China to Japan by translating it for the people of his time in a deeply meaningful way. Thay has done exactly the same: He made Linji Zen acceptable to Westerners. Thay’s genius was to invite everything into the practice: families, minorities, the Earth, everything! Few Zen masters have achieved such a comprehensive and global approach.”

The multifold sangha

“Thay broke the barrier between lay and monastic life,” Prescott said. “He invited me personally to practice as deeply as I can, wherever I am.”

Rowan Konrad, dharma teacher of Open Way Sanghas in Missoula, Montana, shares another perspective:

“TNH would say ‘Catholics have priests. Protestants have ministers. I have both!’ referring to the roles of monastics and laypersons.”

Let’s look more closely at the sangha of the Plum Village Tradition:

Open Way Center in Missoula, Montana, guided by Rowan Conrad and Greg Grallo, serves a network of Buddhist sanghas statewide.

Laypersons – Thich Nhat Hanh created the Order of Interbeing in 1966. This community is committed to living in accord with the practices of Linji Zen.

Monks, nuns and laypersons stand on equal ground in the order, thus emphasizing the role of women.

“Many religious traditions continue having difficulty integrating women: Catholics and Tibetans, for example,” Prescott said. “Thay made gender equality the focus from the beginning. Now the most-published monastics, and best-known living leaders, are women.”

Brian Kimmel, a second-generation Indonesian-American, is among the youngest dharma teachers, or dharmacharyas, to receive “the Lamp of Wisdom” directly from Thay. Dharmacharyas are selected for their stability in practice, and ability to inspire joy in local sanghas.

“I made a personal commitment to Thay that I would be faithful to his teaching,” said Seattle-based Kimmel. “This requires complete engagement, so I structure my life accordingly. TNH restored the Buddha’s view of inclusiveness – across monastics, laypersons, all races and gender identities.”

An altar for Thay at Dharma Gate Seattle, with a respectful cup of tea, honoring the seven-day ceremony of his transition.

Families – How many Zen masters are known for holding hands with children? Thay included families to reflect the accessibility of Zen.

Greg Grallo, of Montana’s Open Way Sangha, said accessibility is at the heart of family retreats his sangha offers every spring , with activities for all ages:

“Inclusivity is an essential aspect,” Grallo said. “We are a ‘family first’ sangha!” ‘

Transmitted dharma teacher Joe Spaeder, of Floating Leaf Sangha in Homer, Alaska, said inclusivity is part of his family’s experience. His family experience is unique, because of their connection to Deer Park Monastery in San Diego, more than 3,000 miles to the south, which Spaeder calls their “home away from home.”

His family attends month-long retreats in San Diego, and his kids grew up with monastics as friends and role models. His daughter, now in college, is a member of the Order of Interbeing, and a leader of the “Wake Up San Diego” Sangha for adults age 18 to 35.

A mindfulness retreat in Alaska, led by dharma teachers Diane Little Eagle, Phap Luu, and Phap Ho.

Young People – The Cherry Blossom Sangha of Seattle is one of four Wake Up gatherings in the region.

“There is a tendency in the United States, and in the world generally, to commodify everything, including religion. There is so much value in building a loving, caring community,” said Cherry Blossom co-leader Nathan Bombardier. “This practice reminds me to feel. As a man, I’ve been taught to ignore that.”

Bombardier looks forward to the return of Friday night gatherings with other sangha members, where they eat and meditate together, “Just hanging out. I’ve made friends and found a community where we help each other.”

Nathan Bombardier, 26, of Cherry Blossom Sangha Seattle, said the practice has helped him be “much more aware.”

Monastics – TNH spent his entire adult life as a monk, founding 11 monasteries, including three in the United States: His contribution to revitalizing monastic life is a remarkable achievement in itself. Someone who can speak with experience is retired monk Phap Tri of Bend, Oregon, who is generally known as “Tree.”

“The monasteries are where people experience how Buddhism can be applied in daily life,” Tree said. “To bring the practice out of the temple and into the homes of laypeople.”

When Tree first arrived at Plum Village as a novice, “I wasn’t really sure if the shoe would fit.” Then Thay gave the series of talks on “Basic Buddhism” that became his book, “The Heart of the Buddha’s Teaching.” These talks significantly affected Tree. Soon after Tree divested himself of all ties to his past life, and fully ordained as a monk.

“The decision to ordain made me,” he said. “I didn’t make the decision.”

Michele Tae, dharmacharya at Beginner’s Mind Sangha in Boise, Idaho, sees this community of monks and nuns across the world as an essential part of Thich Nhat Hanh’s legacy.

“Being able to visit Deer Park Monastery is deeply nourishing,” Tae said, “inspiring my mindfulness practice and my ability to share this practice with others.” Young monastics from Deer Park have toured the Pacific Northwest, encouraging new “Wake Up” sanghas to develop.

A walking-meditation “flash mob” in downtown Seattle, conducted by “Wake Up,” included people 18 to 35.

WRITING DOWN THE DHARMA

Thich Nhat Hanh has written more 100 books about an array of subjects. “Intellectually, he was an incredible scholar,” Tree said.

Tae likes “Transformation & Healing,” based on the sutra of the four foundations of mindfulness.

“This practice benefits from reviewing my life and ways that I have suffered,” she said. “As a chaplain, I have found this sutra useful as I speak to someone who is dying, or who is witnessing the death of a loved one.”

Another significant book Thay wrote is “Old Path, White Clouds,” which creatively presents the life and teachings of the historic Buddha.

“It encapsulates perfectly TNH’s vision of Buddha, dharma and sangha,” said Grallo. “In all of his writing, the use of simple, direct language speaks to true clarity of insight.”

Seward-Magee delights in TNH’s calligraphy, his brushstrokes of meaningful words and phrases. Thay created her favorite example of calligraphy, “I have arrived,” for the Mindfulness Practice Community of British Columbia.

Wake Up members, 18 to 35, celebrate their retreat at Mountain Lamp Community in Deming, Washington.

BEING THAY

Thich Nhat Hanh expressed his personality – including a wry sense of humor – in many ways. A journalist once noted that the Dalai Lama’s title is “His Holiness” and asked which title did Thay prefer? “His Laziness” was the reply.

Jerry Braza, a senior dharma teacher in Salem, Oregon, remembers a time when Thay had a respiratory infection, forcing him to leave a retreat and enter a hospital.

‘Thay has been sick. When I was in the hospital, a young lady came into my room,” Thay told his students. “She said ‘Hello! I’m a respiratory therapist. I’m here to show you how to breathe.’”

Braza remembers what happened next:

A Wake Up retreat at Dharma Gate, Seattle, hosted by the Mindfulness Community of Puget Sound.

“The entire sangha burst out laughing,” Braza said. “Thay laughed at life’s situations – and at himself. He never laughed at others, only with them.”

But another side of Thay could be firm.

“He set strong boundaries. This means the sangha will be safe for everyone,” Braza said. “Once a man was harassing a laywoman during a retreat. Thay refused to start the meditation service. He directed the monks to remove him (the man) from the retreat first.”

Long-time students comment on the intensity of TNH’s presence.

“It was obvious that he gave 1,000 percent of himself all the time,” Tree said.

Prescott said Thay was always living the dharma.

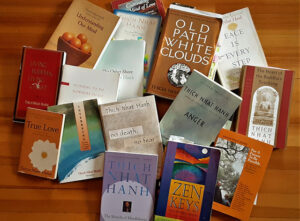

A random sample of 16 books by Thay, from writer Valerie Grigg Devis’ bookshelf, reveals a daunting variety of subjects!

REFLECTIONS ON A LEGACY

In the midst of the Vietnam war, the question for Buddhist monks was: “Should we stay in our temples? Or should we go heal the world?”

Thay’s revolutionary response was to do both, said Spaeder.

“Thay invites us to integrate being on the cushion with the rest of our life,” Spaeder said. “He is a contemplative revolutionary!”

For Lucy Kingsley of Still Water Sangha in Eugene, Oregon, Thay’s moral courage stands out.

“During the war, Thay went to the Buddhist hierarchy in Vietnam three times, asking to be permitted to stop some of the suffering caused by the war – and he was refused,” she said. “Then he took action anyway. That REALLY encourages me.”

Conrad of Missoula said Thay’s engaged approach to Buddhism was all-important.

“TNH would say ‘If it’s not engaged, it isn’t Buddhism.’” Conrad said. “I would not have worked to create Open Way Center here in Missoula without his words.”

Conrad adds that in his view, this is why Thich Nhat Hanh is so important for the future of the world.

“When someone asks why the precepts matter, I say, ‘What if everyone tomorrow practiced Right Speech? Every Politician? Every advertisement?’” Conrad said. “What if everyone’s words were true, kind and helpful? That is how this practice can change the world.”

Valerie Grigg Devis has been a Zen Buddhist practitioner in multiple traditions for over 25 years. She is an ordained member of the Order of the Boundless Way and a senior student with the Salem Zen Center.

During her 30-year career Grigg Devis worked as a land use and transportation planner, and now considers herself now a “recovering bureaucrat.” Grigg Devis is currently pursuing a master’s degree in Buddhist studies through Buddha Dharma University. She also volunteers for Lumina Hospice.

Together with her husband, Jean-Luc Devis, she has planted over 100 new street trees in her Corvallis neighborhood.