Corresponding with Prisoner Pen Pals

Opens New Freedom for Housebound Buddhist

Written by: Valerie Grigg Devis

Shawne Mulloy roots herself in gardening and dharma practice, to deeply exchange letters with prisoners.

Photos by: Deer Park Monastery, Marin Shakespeare Company, Bruce Mulloy

She was “living the good life” – a rewarding career, a handsome, devoted husband, and a home on the Hawaiian island of Maui.

Then multiple sclerosis (MS) appeared. That was the beginning of Shawne Mulloy’s Buddhist practice.

Mulloy was in her early 50s when she received the diagnosis of MS – a disease of the central nervous system that can be highly debilitating and has no known cause or cure. Living with MS was profoundly difficult for her to accept.

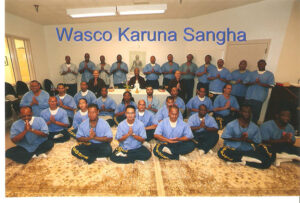

A colleague of Mulloy’s has corresponded with a prisoner from Wasco Karuna Sangha, a Thich Nhat Hahn prison group.

“I was just this raging mind,” Shawne said.

Mulloy had always been a “seeker,” exploring various forms of meditation since her 20s. But now the sense of urgency became very real. A friend offered the book “When Things Fall Apart,” by Pema Chodron. Others directed Mulloy to Maui-based Vipassana Metta Foundation, created by Steve Armstrong and Kamala Masters.

In the dharma Mulloy found what she was looking for: teaching that she called “practical, clear and to the point. It went right to the source of my suffering.” Mulloy also discovered the benefits of practice: “It can calm me down. Everything really is impermanent.”

Her partner in life, husband Bruce Mulloy, reflects on how Shawne lives her Buddhist practice:

Mulloy writing to a prisoner, supervised by her cat.

“She uses the horrible things that happen to her body to stay present. And she remains joyful, in spite of her physical condition,” he said. “She’s compassionate, kind and funny, too. Shawne is very dedicated to her goals: She’s like a pit bull! She’s also the smartest woman I ever met.”

When asked for her own perspective, Shawne said, “My practice is absolutely necessary. It puts color and dimension in a flat, black-and-white world. It’s everything.”

As MS advanced, Mulloy was forced to reduce her engagements with the outside world; retiring from work as a marriage and family counselor, and moving with Bruce to Gig Harbor, a small town west of Seattle. She began to feel “increasingly isolated and irrelevant … like I was living the life of a hermit.”

Mulloy reads a letter from a prison pen pal.

Yet, in spite of her health constraints, she wanted to do something for others. “I was at a low point in my life – especially during COVID,” she said. “I felt like I had something to give…and no one to give to.”

When her friend Steve Wilhelm suggested that she consider a prisoner pen pal program, she was completely surprised.

“I never imagined doing such a thing!” she said. But as she reflected on her own physical confinement, she concluded, “I’m the ideal person for prisoners.”

Mulloy’s journey of Buddhist prison outreach began shortly after COVID took hold in 2020. She began by contacting three organizations that offer prison pen pal programs: The San Francisco Zen Center, the Plum Village Tradition of Thich Nhat Hahn, and a Tibetan Prison outreach called Liberation Prison Project (LPP). Each program offers a slightly different approach to volunteer training and outreach.

Among the readings that Mulloy found useful to prepare for meeting her pen pals were: “We’re All Doing Time,” by Bo Lozoff; “Sitting Inside,” by Kobai Scott Whitney; and “Be Free Where You Are,” by Thich Nhat Hanh.

Michael Willis, Mulloy’s first prison pen pal, acting in “Much Ado About Nothing,” at San Quentin prison.

All three prison pen pal programs accept letters only through the addresses of the sponsoring Buddhist organizations. This means exchanged letters are delayed by about a month, with no direct correspondence between volunteers and prisoners.

Mulloy uses a “pen name” to sign her letters. To date she has corresponded with six male prisoners in four states: Arizona, California, Kansas and North Carolina. Mulloy is not sure why all have been men, but postulates there may be fewer Buddhist outreach programs in women’s prisons.

Michael Willis was her first prison pen pal, a “lifer” sentenced to remain behind bars his entire life. She remembers him fondly.

Willis was a bright man in his late 50s, a gifted writer who sent her his prose and poetry, and who was full of questions about Buddhism. He also performed in a San Quentin production of Shakespeare’s “Much Ado About Nothing,” sponsored by the Marin Shakespeare Company.

When Willis died unexpectedly, no announcement or explanation was given. Mulloy learned about it only when her last letter was returned, stamped “deceased.”

Mulloy has now become a mentor for several of the “guys,” (as she likes to call them.) Two of them lead Buddhist sanghas in their respective facilities, a significant achievement for a prisoner because it indicates they are trusted by prison administrators. Peer leadership is also timely, because outsider leadership is not available due to COVID-19 protocols.

Mulloy taps the harmony of nature, to offers solace and support to prisoners.

What do prisoners write to their pen pals about? “Oh, lots of things!” said Mulloy.

Some need to tell someone what they are going through. Others are lonely or depressed. Some have unending questions about Buddhism: “Can you please explain emptiness?”

Asked what she has learned from the prisoners themselves, Mulloy said, “There’s a real wealth of humanity in prison…their resilience is incredible. They know Buddhism is about ending suffering.”

“Yes, a lot of these guys did something when they were young. But you must realize that their life was s**t,” Mulloy said. “One of my guys was born to a 14-year-old mother and was locked in a basement for days by his foster mother at age eight. By age nine, he was involved in drugs.”

In that case, the “Three Strikes Law” cost him a life in prison. “You can really learn compassion by meeting these prisoners,” Mulloy said.

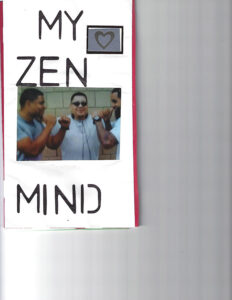

A card sent to Mulloy by a prison pen pal.

One prisoner wrote, “I may be a prisoner, but I can still be enlightened.”

Asked why others might consider becoming a prisoner pen pal, Mulloy said, “Mutual support for our practice is essential for all of us.”

Many prison Buddhists practice alone in a harsh environment that offers little relief from ceaseless noise, random interruptions, harsh lights and a near-total lack of privacy. Challenges have worsened since COVID lockdowns, with visitors no longer allowed to lead meditations or to offer guidance.

In many cases there is no prison sangha. A book, a letter, a few kind words really matter.

Zen practitioner and prisoner Eli Palacios, created this card for Mulloy.

“Some of my pen pals found out about Buddhism by being given a book by another inmate, or finding a book in the trash that someone had thrown away,” Mulloy said. “The inmate writes to the Buddhist organization listed in the book, asks for a pen pal, and the journey begins.”

After more than two years of writing, Mulloy observes, “The process deepens my own practice. When I am asked about the dharma, it causes me to deeply reflect on my own practice and put that into words from my own heart.”

Mulloy has no doubt she has grown in compassion, generosity and wisdom from her exchanges with prisoners.

“It’s so worthwhile to do!” she said. “These guys ask questions and I have to think about it, so it really makes my own practice deeper. And friendships really do develop; It’s a win-win. If you have any inclination to try this, then do it! We are all in sangha together and this is how we grow the sangha.”

Valerie Grigg Devis has been a Zen Buddhist practitioner in multiple traditions for over 25 years. She is an ordained member of the Order of the Boundless Way and a senior student with the Salem Zen Center.

During her 30-year career Grigg Devis worked as a land use and transportation planner, and now considers herself now a “recovering bureaucrat.” Grigg Devis is currently pursuing a master’s degree in Buddhist studies through Buddha Dharma University. She also volunteers for Lumina Hospice.

Together with her husband, Jean-Luc Devis, she has planted over 100 new street trees in her Corvallis neighborhood.