Four Leaders Speak on Climate Change and Dharma

Written by: Jordan Van Voast

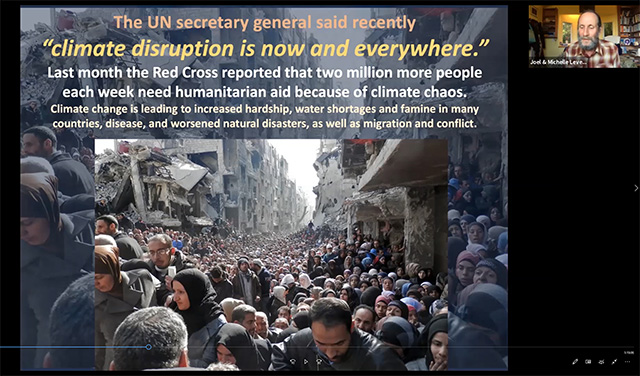

Climate change-caused humanitarian crises are piling up, particularly in the global south. Photos by: Kritee, Joel Levey, Jordan Van Voast

Four presenters brought dharma and related spiritual understanding to the climate emergency, through an online series co-sponsored in the early months of 2021 by two Seattle Buddhist groups.

The series, titled “Interdependence and Our Ecological Crisis,” was co-sponsored by Dharma Friendship Foundation and Seattle Insight Meditation Society.

Yangsi Rinpoche, Geshe Lharampa and president of Maitripa College in Portland, reminded us humans are basically good and encouraged us to plant trees.

Nearly 100 people signed up for the series, which was intended to stimulate discussion and to plant seeds to integrate Buddhist and indigenous wisdom to respond to the multilayered environmental, social and economic challenges facing our shared world. The presentations highlighted people’s growing willingness to face these issues and work together towards solutions – both internal and external.

Guest presenters drew from diverse experiences and traditions to touch on many themes, with several key foundational understandings emerging. Most notable was the thought that we must eliminate inner delusions that view humans as separate and independent from nature and each other, if we are to heal the atmosphere, the oceans and rivers, the forests and other communities of living beings.

The first presenter was Yangsi Rinpoche, president of Maitripa College and spiritual director of Dharma Friendship Foundation, who shared his personal reflections on the changing climate.

Rinpoche started by describing his own observations of decreasing annual rains, and rivers turning into sand, when he was as a young monk in South India. More recently he became a temporary climate refugee when he fled Portland in September 2020, when the Pacific Northwest registered the worst air quality in the world during 10 days of wildfire smoke.

Fern Naomi Renville (Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate/Dakota), and Roger Fernandes (Lower Elwha/S’Klallam) led a discussion on indigenous sovereignty as a vehicle to heal the planet.

One participant noted that His Holiness the Dalai Lama has mentioned the role of non-violent protest in demanding that policy makers change laws. While Rinpoche acknowledged this strategy, he spoke of the need for actions to come from a calm and spacious mind, not angrily pointing fingers in blame.

“Each of us bears responsibility in creating the problem, and each one of us has a role in the solution,” Rinpoche said. “We must work together, beginning by being more mindful of our individual carbon and water footprints, and reducing our use of plastic.”

Rinpoche encouraged us to support projects that plant trees and rehabilitate the land. Underscoring the need for patience, he recounted the Tibetan Buddhist story of Asanga’s 12-year retreat in which he often became discouraged. But each time Asanga left retreat in frustration, he witnessed very simple occurrences that inspired him to continue his meditations.

Storyteller and playwright Fern Naomi Renville started the second presentation by saying to everyone “Mitakuyape, Good morning my relatives,” in her native Dakota language. She explained that we are not just related to each other as humans, but also to the rocks, rivers, forests, and creatures that swim, walk and fly.

Roger Fernandes, an indigenous artist, is dedicated to informing people about native perspectives on climate change.

Storyteller and visual artist Roger Fernandes then presented the online radio play “Changer and the Star People,” after which Fernandes said, “Chief Seattle spoke of how we are all in a web connected with each other. Anything that happens to one part of the web will affect everything else. The Earth does not belong to humans, humans belong to the earth.”

Fernandes is a member of the Lower Elwha band, S’Klallam, and a collaborator with Renville.

When asked how to find hope during a time of potential ecological catastrophe, Renville said, “You have to change the stories told by the culture. By changing the story, you change the forces on the material plane as well. Now, some places – rivers and mountains — are recognized as entities worthy of protection. These are the elders we need to talk to.”

Renville said a skillful legal avenue for protecting Mother Earth is to contact one’s legislators, and ask them what they are doing to uphold indigenous sovereignty and treaty rights. In closing Fernandes sang the Changer Song with the heartbeat of his drum, and urged as all to “Be the Changer.”

Kritee Kanko, Ph.D., engaged listeners with her unique background as a Zen priest and as a climate scientist working with rural farmers in India.

Climate scientist and Zen Priest Kritee Kanko, Ph.D., began the third presentation by quoting senior monastic Bhikku Bodhi: “Buddha understood every community’s well-being to be dependent upon the state of mind and actions of involved individuals.”

Kanko described three interconnected traumas: 1) human trauma that often arises in childhood, 2) climate and ecological trauma due to reliance on fossil fuels, industrial activity, and patterns of human consumption, and 3) racial trauma.

“We can’t solve the climate (crisis) now and then come to racial healing, when racial inequities are one of the causes of the climate crisis,” she said. “You can’t do it in reverse order.”

How do we deal with all three challenges? Kanko’s “Dharma of Resistance” course is based on a three-part equation: “Healing individuals (trauma resilience), plus shared village life and mutual aid (including a massive reduction in greenhouse gas footprint), plus strategic resistance, equals islands of sanity in a sea of chaos.”

Opening to the scale of the crisis can be overwhelming, and pausing with the breath gives us the strength to stay engaged.

Kanko offered an alternative response to the growing social movement of seeking to adapt to a dying planet, which she said can lead to a loss of hope and then a sense of apathy or impotence.

“A bodhisattva takes vows to do impossible things, to relieve the suffering of all sentient beings,” she said. “There is a sutra of a crow that carries drops of water in its beak to fight a forest fire. You might say it’s stupid, silly, just make peace with the fires. But I don’t think that is an option. Doing the right thing regardless of results is definitely one part of this.”

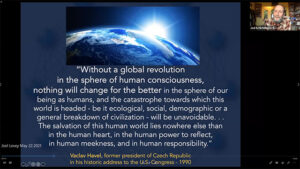

In the fourth presentation, Dr. Joel Levey offered a blend of perspectives from the front lines of ecological activism, science and government policy makers, blended with ancient spiritual teachings on how to awaken the heart-mind and become a healing force of compassionate altruism in the world.

“Climate disruption has arrived – we’ve crossed the line,” he said. “It is not a debate over whether it’s happening, but a debate over how we respond.”

Buddhist teacher and consultant Joel Levey, Ph.D., led the audience on a deep dive into the overlapping global challenges of our time.

Joel Levey and his wife Michele Levey were instrumental in bringing mindfulness teachings to the West half a century ago.

Throughout Joel Levey’s presentation, and during the following discussion, the emphasis was on how to respond appropriately and skillfully, with compassion and awareness of our interconnectedness.

Pointing repeatedly to Joanna Macy’s “Work that Reconnects,” Levey advised us to always begin with gratitude for the inherent beauty in the world and each other, to open to the suffering around us and the death of ecosystems, and even the uncertainty of humankind’s future. But despite all this, he said, we should not get stuck in empathic distress.

The climate emergency is a spiritual imbalance that can be healed.

“There is no such thing as compassion fatigue,” he said. “Compassionate engagement is the remedy.”

“This is a dark time filled with suffering and uncertainty. Like living cells in a larger body, it’s natural we feel the trauma of the world,” Levey said. “Don’t be afraid of feeling this because it rises from the depth of our caring. Sorrow, grief and rage are a measure of our humanity. We need to perfect compassion and in order to do that, we need to encounter suffering.”

Referring to the Hopi prophecy that speaks of a time of great change, chaos, and transformation, Levey encouraged us not to cling to the shore, to develop our community networks, to cultivate a regular meditation practice, and to let go into the unknown as we do our best to alleviate the suffering within and around us.

Echoing the Hopi prophecy, Levey ended, “This could be a good time.”

Jordan Van Voast engages in disaster and community relief work as an acupuncturist, and serves on the board of Dharma Friendship Foundation. As an activist he currently is working with Seattle Cruise Control, a group focused on stopping cruise ship expansion in the Salish Sea. A vegan, he is a year-round gardener and enjoys walking meditation in the wilderness.