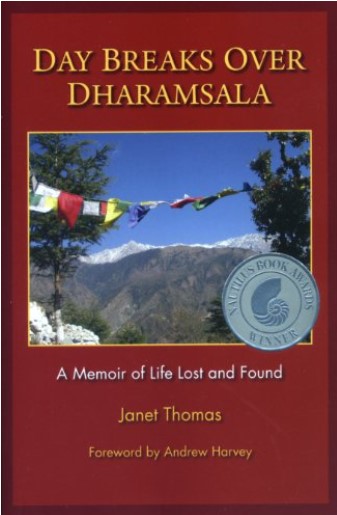

Day Breaks Over Dharamsala: A Memoir of Life Lost and Found

Day Breaks Over Dharamsala: A Memoir of Life Lost and Found

By Janet Thomas

Well, this is a very long post–the final chapter of my book, “Day Breaks Over Dharamsala–A Memoir of Life Lost and Found.” The book is about my first trip to India which happened because of my dear friend Thrinley DiMarco. It ends at Christmas, in Dharamsala, home to HH Dalai Lama. It was 2004 and Thrinley was going to India to attend the Long-Life Ceremony for His Holiness Sakya Trizin who is the brother of H. E. Sakya Jetsun Chimey Luding Rinpoche, who is the founding teacher at Sakya Kachod Choling, the Tibetan Buddhist Gonpa on San Juan Island. I couldn’t possibly let Thrinley go to India alone! Thrinley died this year–in April. I did not know she was ill and COVID times put a local celebration of her life on-hold. She is with me and always will be. That trip to India became the first of many. It was also the most momentous experience of my life. I’m sharing this last chapter because it is Christmas time and this is the year Thrinley passed into her next life. This final chapter of the book became the first chapter of the rest of my life. I have a heart full of gratitude for Thrinley. And for India.

Chapter Twenty-Seven

His Holiness Comes Home for Christmas

They have great cakes in Dharamsala and Matt and I are searching them out for our Christmas Eve daytime dinner at his friend’s place in Dharamkot. Matt has invited me to join him for this event and I think I am grateful, although I’m not sure. I was ready to spend the day on the beloved patio, drinking tea, writing in my journal, and daydreaming about life as a dog in Dharamsala. Matt, however, caught me at my reverie and spirited me away. We get boxes for the big creamy confections and set out on our walk to only Matt-knows-where.

We start out on the road to Tushita and after about twenty minutes head off on a trail across the hillside. Another twenty minutes gets us to a house of cement, color, and wrought iron. There is a patio area out front where food fills a big low table and young people are sprawling around eating and chatting.

I am wondering why Matt invited me along. I thought there would be two or three people at this afternoon dinner, but this is obviously a party, and nobody is over thirty. Then I find out from one of the young people that the Dalai Lama is coming back to Dharamsala today. Maybe right this minute. I am so pissed I could spit. Here I am at a gathering of young people all infatuated with themselves and one another when I could be back in town welcoming the Dalai Lama home. The yearning to see the Dalai Lama has been kept at bay by the circumstances of his absence. With that no longer in play I am suddenly obsessed with the possibility. It turns me into someone who doesn’t like these lovely people who have so kindly included me in their Christmas dinner. But I am not confident enough to find my way back by myself, so I sit and suffer.

It is 3:30 by the time Matt and I head back to town. As we walk, I chirp on in friendly fashion about nothing of significance, feigning obliviousness to my pissed-off impatience about the afternoon. Then, as we walk through town, Matt suggests we buy a Christmas present for the monks.

Okay. Fine. Be nice. See if I care.

I am, of course, struck by the perfection of his suggestion.

“Let’s get them a thanka for the lobby,” says Matt.

“Yes, let’s,” says I.

We go in to the thanka shop where beautiful Tibetan Buddhist hangings of all sizes and deities fill the space with brilliant color. They are all made by monks who also run the shop so it is fair trade in all directions.

“How about Chenrezig?” says Matt.

“How about Chenrezig,” says I. After my forty years of Buddhism and his four weeks, it is Matt who can say “Chenrezig” and know that it’s the precisely right deity for the occasion.

Chenrezig is the embodiment of compassion, the One Who Gazes Upon the World and Sees the Suffering, the One Who Refuses to Become Enlightened Until Everyone Else Does. Including me. And that is the sobering thought-of-the-day.

Chenrezig has anywhere from four to one thousand arms because two arms is not enough to hold the suffering world. Neither is one head. It is said that Chenrezig’s head broke into eleven pieces when he became overwhelmed with the needs of so many sentient beings. His Holiness the Dalai Lama is believed to be the earthly manifestation of Chenrezig.

Chenrezig has other names, too; Avalokiteśvara is the Sanskrit version and it is a word I learned to say years ago when I was cooking at the retreat center. A-val-o-ki-tes-vara cried so many tears of compassion for the plight of us all that the millionth tear gave birth to the lake upon which floated the lotus that gave birth to White Tara, the Mother of Liberation. It was no accident that I memorized the difficult name of the deity that cried a million tears and could not stop.

The Chenrezig we select for the Loseling monks has four arms and is bordered by two layers of beautiful brocade. It comes ready to hang with a protective silk covering the color of saffron. It is beautiful and expensive. We will give it to the monks tomorrow, Christmas Day. They are already thrilled because Christmas coincides with a commemoration day for some special historical teachers and they will be eating chicken, beef and “pig.” It is an immensely rare culinary occasion to which Matt and I have been invited.

We are pleased with ourselves when we get back to our rooms. I give an English lesson to Dakpa and then head off for the Christmas Eve service at Saint John’s in the Wilderness.

I don’t do Christmas well. No matter how well I prepare, it is never enough to save others close to me from my meltdown of mind and emotions. I am an undercurrent of cynicism and repulsion, a mire of self-hatred and hatred, a child’s urge to excitement and pleasure accompanied by a child’s heartbreak and disappointment. I love the season because it is full of heart and generosity. I hate it because it is a trick. I spend money wildly. I get lost in irreparable grief. I try to be good, to hold to some sort of equanimity as the good tidings go by. I fail at every attempt to do so. At no other time of the year does desolation so effectively do its dirty work on me and on my relationships. I get totally fucked-up and there is not a thing I can do about it.

If one is analytical, this holiday meltdown makes perfect sense. The litany of my upbringing—that I am beyond bad and there is nothing I can do about it—triumphs at Christmas. It tells me that I am a lost cause, that healing is a lost cause, and that the world is nothing but lost causes trying to fool themselves into some gruesome representation of good. I understand the idiocy of all this when my own personal undercurrents get the better of me. But it doesn’t make the feelings go away. This struggle to feel at home in the generative world, to feel as though I belong in the human family, is invisible. I am perceived as grown up, responsible, creative, accomplished, active in my community, intelligent and sensitive. These are easy things to see. What is invisible is the feeling of defilement that shadows every gesture towards being “good,” towards what I “love,” towards “life.” I write these words in quotes because sometimes they are as science fiction to me as the word “satanism.” On bad days, we mock one another. On good days, “love” and “life” are real and can be spoken.

Even after decades in recovery through psychotherapy and spiritual practice, this idea, that to be good is bad, wrestles within me constantly. As a child, I knew “good” as a lie because it was a mask for cruelty. As I grew up it became a more diffuse affliction. Goodness was rooted in hypocrisy. Fighting through this belief system has affected everything in my life – from harboring a hatred of my own worth to a penetrating mistrust in the good intentions of others. This is a dilemma of the soul. Knowing ourselves as meaningful, as belonging to life, as a natural part of a creative universe, as “good,” means knowing ourselves soulfully. It is the recovery of our spirit that gives us, finally, our place in the world.

The skills that I developed to survive my childhood turned out to be spiritual skills. But it took many years and this trip to India to fully realize this, to get back my Self in all its peculiar grandeur, and to know not simply survival, but triumph. It is with those who have suffered, survived, and triumphed where I find solace in this world. It is what His Holiness the Dalai Lama represented to me so many years ago when the news of his escape to India first reached my attention. It is what the Tibetan Elders represent as they, some with great difficulty, circumambulate the Lingkhor each morning. It is what I gleaned from the exuberant, joyful monk meditating in silence and solitude on top of the mountain. It is what the Khampa warrior taught me with his fight for freedom and his passion for the language of freedom.

My own states of being often disintegrate into childlike parts and irrevocable sadness. Grief that is unassailable. But when I get back from the brink of it all, it is always the stalwart in spirit who guide me, those whose lives have gone through the darkness and who stayed in faith and love on their spiritual path. My own ability to do so wavers on a daily basis. If the spiritual stalwarts were not in the world, I wouldn’t be. I know that completely. On this trip, I have found freedom for all of me.

India’s rollicking diversity is exuberant with personal democracy. Yet there is also shocking discrimination and cruelty. Women are chattel, held behind bars and sold for sex. Children are oppressed and suppressed under the best of circumstances and raised and sold as sex slaves under the worst. Poor people grovel in unimaginable filth. The caste system, long illegal, still has a firm grip on the country’s psyche. Yet behind it all, underneath it all, and in spite of it all, there is spirituality. Not the easy kind that sputters up from an overfed, over-stimulated, over-indulged society in search of “meaning,” but the kind that roars out in joy in the face of death and deprivation. It is an utterly nonsensical spirituality. It permeates the suffering. It is the suffering. It also permeates privilege and the privileged. Somehow, spirituality in India arrived before the people, took hold in the landscape, locked on to the very meaning of being, and hung on for dear life. And in India, life really is dear, just as it is expendable. The very deeply held bodily belief in reincarnation creates an almost giddy sense of acceptance of one’s lot in life. Having a bad life in India is like having a bad day. Soon it will be over and there will be a new one.

So, I have run away to India for Christmas and found Saint John’s in the Wilderness, an old colonial stone church on the edge of town where there is no priest, no pedantry, and no place to sit. The place is overflowing. I have to push my way inside where hundreds of people are crammed together in good spirits and bad singing.

There are Tibetan monks, Indian families, European tourists and an array of Buddhists, Muslims, Hindus, Jews, Christians, and a collection of those old Saint David’s favorites—skeptics, non-believers, doubters and the gloriously confused. We sing carols in one another’s languages and the buoyancy of hope and possibility is palpable in every breath. I am completely overcome. Tears flow down my cheeks like a river; I cannot catch my breath. It feels as though we could light up the world.

The small Indian man, the church caretaker, who gave last week’s sermon is bursting with pride and joy. He is surrounded up front by a crowd of people, mostly Westerners, participating in the service. He ushers them forward to read their favorite passages and to lead us in holiday songs from their countries. Two Indian women give a beautiful full-voiced rendition of “O Come, O Come Emmanuel,” an elegant counter to our communal sing-along. There is a pretend birthday cake for Jesus where children put white candles and then stand gazing into the flickering lights.

The church darkness is also lit by colorful strings of lights and shining tinsel. As I watch the creative chaos amongst the group up front with the gentle Indian man, I realize that this is what he had invited me to, the participatory process of this Christmas Eve tradition in which the company of strangers becomes a great gathering of spiritual friends.

It reminds me of the children’s Christmas pageant back home. Years ago, I was asked to coordinate it and because I was saying “yes” to everything that was asked of me at Saint David’s, where West Davis had opened my eyes to the possibilities and impossibilities within my own faith tradition, I took on the task. I knew I was in way over my head when the very children who showed up for rehearsal were the ones who knew they would not be around for the performance. Going to rehearsal was better than nothing.

It all had to do with dressing up. Beards and wings and cloaks and loads of sparkling things made for a great get-up of one sort or another. But not making it to rehearsal had its consequences. Angels wandered the aisles in search of their parents, sheep sucked their thumbs, shepherds jousted with their staffs and Wise Men wisecracked their way through the script. Joseph was usually half as tall as Mary and Baby Jesus was a doll often handled with a startling and casual carelessness. The only role taken seriously was that of God. It was the only role that was fought over. My only requirement was that God showed up for both rehearsal and performance. God’s costume was always a challenge and the solution was always more of anything gold. I knew it was sacrilegious to write words out of the mouth of God, but it seemed to me that God deserved a voice in the pageant. After all, God was ultimately the real reason we were all there.

I grew to love those pageants. My favorite part was watching the parents dissemble as they realized there was no real organization other than their kids’ on-the-spot desire to dress up and get attention. One year we had a real donkey for Mary to ride, and two favorite dogs as camels. There was nothing for a parent to do but sit back and pray.

I’d been so held captive as a child that I could never even begin to rein in the Christmas Pageant kids to whatever was deemed “good” behavior. My directorial inclinations held no weight whatsoever with me or them. But they knew I was on their side and I knew they were on the side of all that is good. So, they rose to the occasion accordingly and honored the true nature of Christmas— birth of all that is beautiful, joyful, and spirited. No matter what the bloopers were, the annual pageant-goers loved the blissfully spontaneous nature of things. And the kids, utterly unaware of their own grace, basked in the love and appreciation. They were directing us, me most of all, and it is something I will never forget. Out of their innocence I could see my own. And if they could do communion, so could I.

The children gave me courage and it was at one of those pageants, years ago, that I joined them for my first ritual of bread and wine. It was a moment infused with the innocence, wonder and rambunctious glee of childhood. Communion. It was a moment free of the gravitas of “meaning;” it was a moment of simply “being” and “being” with those children was silly and sweet and sublime. That’s all there was to it. But there is no communion tonight because there is no official priest on duty. It is simply our human communion that connects us, despite our divergent cultures, religions and beliefs.

After the service, there is much milling about outside in the dark and I get a whiff of coffee in the air. This is a shock as coffee is no staple here in India. I smell my way to a long table full of plates of cookies where cups of coffee are being served in honor of all us foreigners away from home at Christmas. I bump into Matt in the crowd. He is with a friend and they are on a mission. Someone he knows asked him to find the burial place of a woman who died here in Dharamsala and is buried in the cemetery at St. John’s. They are to honor her gravesite for Christmas.

I start back along the road to town and find myself walking behind a family of five people, two Tibetan children, a Tibetan man, a Caucasian woman, and another woman who might be her mother. They are all, including the children, speaking “American” English and exhibiting American exuberance. The two children are the ones I noticed gazing into the candles on Jesus’ cake. It is clear and cold and I feel secure walking alone behind them. We’ve gone about a quarter-mile when an open jeep stops and offers the family a ride. The Indian driver waves at me to join them. I pile into the merriment of the crowded situation and the driver takes us all into town. All the way he wishes us a Merry Christmas.

All the way from the town square to the guest house, people wish me a Merry Christmas. They are delighting in recognizing that I am someone to whom Christmas has meaning. It is as though the occasion identifies me with spirit and it is something reassuring, familiar and trustworthy. I go to Jimmy’s and get two pieces of banana toffee pie. One to eat tonight under the night sky of Christmas Eve, the other I’ll eat for breakfast.

Nothing could have prepared me for Christmas in Dharamsala as my own personal convergence zone. All the loose ends of my long and convoluted life-journey have transformed themselves into a tapestry of faith that I can finally see and understand. The sense of isolation that has been my constant companion has been replaced by a deep and deeply reassuring sense of belonging. I no longer feel as though I need to be fixed. My “craziness” is the craziness of India. Nobody can fix it because in some profound way, there is nothing to fix.

I have always been guided towards faith and hope, even when I had none. Sustaining grace always intervened when life seemed inconceivable. It is a grace outside my control. It manifests itself in nature, in synchronicity, and in faith that everything that happens has spiritual meaning. These days it is not easy to confess to faith, to the religious impulse, to the possibility of encountering the Divine in ordinary life. Just as it does not make it easy to confess to an experience with evil.

But here in India, daily life is infused with celebration of the spirit and protection against evil. Buddhist and Hindu rituals, shrines, stories, and temples are just a few of the ways in which religion sparks the sensibilities of day-to-day living. It is religion that lights up life and landscape with color and joy, even as so many Indian and Tibetan people’s lives are rooted in terrible suffering. I am discovering that grief and love are the fundamental links to life, to the living, to healing and to belonging.

Weaving through these five weeks in India is a lifetime of longing, of continually starting over on the doorstep of my own life. I have finally crossed the threshold. I have experienced Hindus and Buddhists celebrating life and religion side-by-side, inclusively, with lots of room for a stumbling Episcopalian along the way. I’ve experienced the buoyancy of people and place as well my own buoyant and healed self in a place that I recognize and that recognizes me. It has been a spiritual, emotional, and psychological homecoming, an epiphany from beginning to end.

The deepest truth is that every day is a profound and miraculous mystery. And we are gifted with the consciousness to know this. And we are gifted with the knowledge and the power to fix what is wrong in the world. Waking up to the truth is waking up to tragedy. It is also waking up to our responsibility to the world, to our place in the world and to our power in the world. A power fueled by spiritual truth.

What happened to me, and why, can be explained. The evidence abounds. But how I was protected, nurtured, and sent along my spiritual way is an immense and majestic mystery. It is on this trip to India that I am recognizing what was always in attendance—an inextinguishable flame of spiritual guidance that knew me from the very beginning. It is why these words are on this page. It is why I am happy to be alive. It is why the very nature of being is sacred. We are here on earth to honor love—for our lives, our earth, and for one another. This is what I am waking up to in India. This is what I have known my whole life. It is beyond me. It is beyond us all.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

On Christmas morning I wake to my small array of items on the table, the cards, the candle, the incense, and the toffee pie. Dawn is just a hint in the sky. The Dalai Lama is back in town. He is here. This man, whose very life has been a guiding star to me for more than forty years, is less than a mile away. I know enough about his routine to know that he has been up since four, meditating and praying. That these days he wakes up in an earthquake protected room depriving him of his beloved view of the Dhauladhar Mountains. Perhaps, after his prayers, he goes outside to his gardens to hear the morning birds and watch the sunrise. He came back from south India to his Dharamsala home on Christmas Eve.

Perhaps he, too, wanted to wake up here this morning, to know home on this sacred day, even if he is not a Christian. Yet, I know he is. He has been walking through the fire of human hatred and violence since he was a small boy, compassion firmly guiding his steps and his heart.

“Forgive them for they know not what they do.” Reportedly, these were Jesus’ first words from the cross. They speak the fundamental shape of compassion born out of understanding — whether from the earthly realizations of the Buddha under the Bodhi tree or the transcendent relationship of Jesus with His God. There is no other way to live. To defy this understanding is to choose death and destruction. When we forgive in the face of cruelty and brutality, whether of a regime, an institution, or an individual, we take the side of life, the unfolding miracle of creation that insists itself into light. Cruelty becomes an aberration, an indication of that which is less than life. Understanding and forgiveness is the high road—and the only road to a future.

The words in the poem that has accompanied me on this trip finally sink into my psyche.

To make injustice the only measure of our attention is to praise the Devil, writes Jack Gilbert.

It is a very terrible thing to keep suffering just because it proves I have suffered. It becomes another way of keeping myself imprisoned, of worshiping the Devil, of giving power to those who wished me powerless.

We must have the stubbornness to accept our gladness in the ruthless furnace of this world.

I will be stubborn.

If we deny our happiness, resist our satisfaction,

we lessen the importance of their deprivation.

I will not deny my happiness.

We must risk delight. We can do without pleasure,

but not delight. Not enjoyment.

I will risk delight.

Delight. It is bigger and brighter and stronger than us all. It delights in itself and in everything it reaches. It is everywhere in India. And it was here last night, in the old stone colonial church on the edge of town. We were directed through that which is always there, waiting for us to wake up to—grace, beauty and understanding.

This is precisely what I’m trying to remember to wake up to this morning. But, of course, I feel lonely and slightly dotty. There is no-one to share the morning with, no Christmas morning call from my son, nobody to fix dinner for, and no bacon to cook for breakfast— which is one of my Christmas sins. Just the sun, rising brilliantly from the east, the birds singing, the dogs barking, and the monk circumambulating the roof.

Our Loseling monks have invited Matt and me to lunch today. It is for Christmas and there is also a Tibetan holiday to celebrate. They are excited because there will be three kinds of meat and meat is no staple in their lives. There will also be visiting monks chanting in the room behind the kitchen while we eat. Matt and I will give the monks the thanka we bought yesterday. I will give Dakpa some warm fleece sweat-pants, a dictionary, a notebook, some pens and some money. He will be here for an English lesson this afternoon. In a minute I will go and walk the Lingkhor and the doors to the Dalai Lama’s compound will be open for the first time since I arrived in Dharamsala. I could explore the possibility of a visit, but I know I won’t. Because it is finally time for me to learn what he has already taught me.

There are things wrong in this world. They manifest themselves in violence against the innocent. They are arrogant with power and rampant with greed. But even when evil gets its way, it does not win. Because what is good prevails effortlessly and takes hold naturally. There is always someone who will turn the other cheek and see the light. There is always life rising out of the ashes. There is always something to learn that will make a difference, and always someone to learn it from.

I sit with all this in a state of something akin to prayer. I am waking up on Christmas Day in Dharamsala. I am alone with it all. I miss my son. I had no idea why I was coming here, and I discovered it was because I had to, that there was a pilgrimage to take and that it could not be taken without me. I miss Thrinley. I miss the company of friends and right now even of strangers. But the Dalai Lama is just across town and the Christmas card from Dakpa has a Tibetan Santa Claus and prayer flags across the top. The card from the dear Loseling monks says “Christ’s Birth” on the front and shows Mary and Joseph in the manger.

So, I will be a Buddhist and a Christian, too. I will go to church, to the gonpa, to the green cathedral of the outdoors, to wherever it is that stands up for the love of life and I will belong. I will live. I will be holy. I will be happy. And nobody can tell me otherwise.

I wrap myself up yet again against the morning chill and take my Christmas toffee pie out on the patio. There is no cloud in the sky, no protection from the onslaught of mountain beauty rising above the morning streets already filling with breakfast for the cows, monkeys, and dogs. After their morning meal, the dogs will come out to stretch, sleep, and perhaps dream, in warm patches of sun. It is all happening all at once yet again. It is Christmas and I am here.

The patio is fresh with new paint. In a while, Matt and I will meet for tea and perhaps discuss reality. In the meantime, my breakfast toffee pie is sweet and tasty. It is almost as good as bacon.

The End