Western Monastics Flourishing in the Northwest

Written by: Karen Ferguson & Luke Clossey

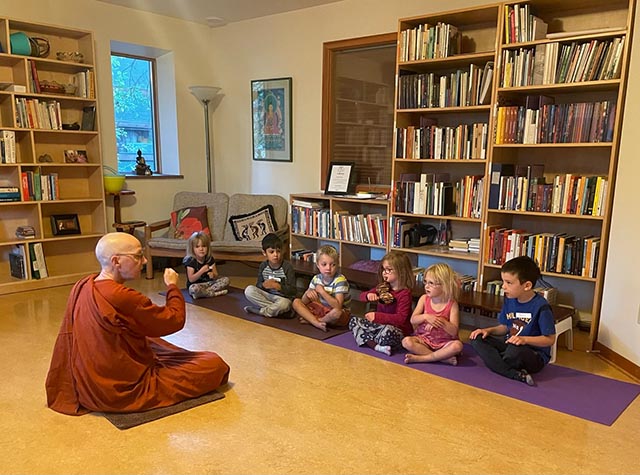

Ayya Ahimsa teaching dhamma to young children

Thirty years after the founding of the first Thai forest Theravada monasteries on the West Coast of North America, the tradition is flourishing and expanding among Buddhist converts, many of them relatively young.

The first monasteries – Wat Metta (1991) and Abhayagiri Monastery (1997) in California, and Birken Forest Buddhist Monastery (Sitavana) (1994) in British Columbia – are being followed by others supporting both female and male monastics. This is perhaps surprising in 2024, given that this monastic tradition is among the strictest and most orthodox of the Buddhist world.

New monastic institutions being established in the region are often pioneering new models for independent monasteries and branch hermitages. The Clear Mountain Monastery community meets in a Seattle Christian cathedral, in individual homes, and online as they look for a suitable long-term property.

Abhayagiri recently opened the Three Jewels branch monastery in Fort Bragg, California, in a house bequeathed by a long-time lay supporter. Practitioners on Vancouver Island have founded the Aranya Refuge Theravada Buddhist Monastery, to host monastics from Wat Metta. In Alberta, Ayya Ahimsa now lives at the Canmore Theravada Buddhist Community (CTBC) monastery.

Meanwhile, Portland Friends of the Dhamma, established at first to support the founding of a nearby Abhayagiri offshoot, the Pacific Hermitage (est. 2010), has innovated a new form of an urban lay Buddhist center. Portland Friends focuses on teachings from, and support of, monastics mostly from our region.

In addition, a number of bhikkhunis live in outposts that are more solitary. Last October, at Port Townsend in Washington state, Anagarika Bethany became Samaṇeri Junha. This was an ordination presided over by her female monastic teacher Ayya Anandabodhi, and witnessed by monastics from CTBC and Clear Mountain.

Ayya Niyyanika spent the 2023 Rains Retreat on Bainbridge Island outside of Seattle, frequently engaging with the Clear Mountain community. Until recently, Ayya Nimmala offered teachings to lay supporters from Dhammajivi Vihara in Vancouver, B.C., while living there to support her parents.

Not Following Expectations

None of this flourishing was supposed to happen. In the 1990s Ajahn Amaro, a founding co-abbot of Abhayagiri Monastery, was spying out the Pacific Northwest. He was on a mission to learn whether traditional Theravada institutional arrangement – lay people supporting monastics – could work here. As he explains in his 2007 book “Rugged Interdependency,” the informal, urban vipassana groups he found—”far from the shop-til-ya-drop mentality of materialistic America”— impressed him for their adaptability and receptivity.

However, the region did not seem to be calling out for monastics. Ajahn Amaro noticed a hesitation about bowing and chanting, about devotion and ritual. Even people’s motivations and understandings of the Buddhist path clashed with traditional beliefs. Locals seemed to come to meditation groups for psychological reasons, to get rid of their problems, not for awakening.

Ajahn Amaro could appreciate the benefit of that worldly aspiration but reflected that, “The longer this premise is followed blindly, the greater is the resulting anguish. According to classical Buddhist understanding the person doesn’t have problems, the person is the problem.”

Observers writing more generally about North American Buddhism have come to similar conclusions. They have portrayed white meditators as dismissive of traditional Asian Buddhism, which is very much a religion grounded in monasticism and the transcendent, and not just a contemplative practice. Indeed, many North American converts who call themselves Buddhist have described their approach as the “true” and “original” Buddhism, uncorrupted by what they see as centuries of accretion of Asian superstition, formalisms, and hierarchical institutions.

In theory, the culture of the Pacific Northwest should compound this aversion to monasticism. Scholars have long regarded it as the least religious region of North America, where the spiritually inclined tend to cultivate relationships with nature or eclectic personal beliefs, unimpeded by institutions and orthodoxy.

Nevertheless on December 31, 2022, a multi-generational group of hundreds of laypeople, mostly converts to Buddhism, assembled over Zoom and in person to celebrate the New Year. Their host was the Clear Mountain community, “an aspiring Buddhist forest monastery in the Greater Seattle area.”

Participants formally took refuge in the triple gem, made the determination to keep the five precepts, and chanted 108 itipisos – many keeping count with mala beads blessed by Thai Kruba ajahns during a recent pilgrimage to Thailand and India. Presiding over the event were two millennial American-born monks: Ajahn Kovilo and Ajahn Nisabho.

Explaining the Unexpected

How then has monasticism taken root in the Pacific Northwest? We set out to find out. As historians from Simon Fraser University in Vancouver, B.C., we have written and lectured about the establishment and growth of Birken monastery, and are currently researching the expansion of forest monasticism along the West Coast. We have found that many of the factors that contributed to Birken’s success are still in play in these new monastic forms today.

Born and Born-Again Buddhists

Contrary to expectations, we have found that North American convert lay people supporting this tradition, like those at Clear Mountain’s New Year’s celebration, do like ceremonies and ritual. In addition, the presence of people born into Buddhism in Thailand or Sri Lanka, can make a huge difference for these new lay monastic communities. The faith and behavior of born Buddhists can serve as an informal model of traditional approaches, and their cultural knowledge and understanding of the dhamma can make them community leaders.

They can show newcomers how to “do” Buddhism, and often provide existential support to monastics, as converts learn the ropes of their role in monasticism. Meanwhile, some enjoy finding in North America a flourishing monastic orthodoxy that is often uncommon, or marginal, in their home countries.

Flexibility and Rules

Forest monastics are among the strictest adherents of the vinaya (monastic discipline), even in challenging non-Buddhist environments like Cascadia. Laypeople in the Pacific Northwest find that the vinaya, with its clear ethical boundaries, builds their confidence in monastic teachers’ behaviour and teachings. Lay supporters have learned to appreciate and take joy in their essential role in maintaining monastic discipline, for example by offering food on monastic alms rounds.

Focusing first on the value of monastics’ dhamma teachings, many lay supporters have shown open-mindedness in their respect for and support of both male and female monastics in the forest tradition. This is despite disagreements within the ordained sangha about the higher ordination of women. Many laypeople in this tradition simultaneously learn from and support nuns and also monks, even monks who do not recognize bhikkhuni ordination.

Meanwhile a new wave of monastics, like those leading and drawing near to the Clear Mountain initiative, are forging a way for reconciliation and reciprocity between bhikkhus and bhikkhunis, within vinaya observance.

Networks, Physical and Virtual

None of these new institutions is developing in a void. Each is combining local lay support with monastic teachers coming from established monasteries far and wide. Arrangements vary. Three Jewels is a formal branch monastery of Abhayagiri, and Aranya Refuge was established with Wat Metta in mind.

Although an independent undertaking, Clear Mountain regularly invites monastics from around the world to teach in person or virtually. CTBC used its connections with institutions in Ontario and California, in its long quest for a suitable resident monastic.

Each also benefits from virtual networks, in a region where people have been building online communities since the earliest days of the internet, and where sky-high property values have made establishing brick-and-mortar monasteries a daunting endeavor. Every forest monastery we know of in Cascadia has sought to build online connections between monastics and laypeople, through live meditation sessions, teachings, and discussions on Zoom and YouTube. Most also forge community among laypeople through channels like internet discussion boards, Facebook groups, and Discord servers.

Conclusion

While some stereotypes of Pacific Northwest religion may be true, it turns out a growing network of practitioners in our diverse region support forest monks and nuns and their monasteries. Human suffering is universal. At least some people in the Pacific Northwest are finding that monastic teachers are the best guides, not only to happiness in this life, but to liberation from samsara and suffering.

Karen Ferguson is a professor of urban studies and history at Simon Fraser University, in Vancouver, B.C.

Luke Clossey is an associate professor at Simon Fraser University, where he teaches global history and the history of religion.