Sister Jendy: A Unique Buddhist Monastic Leader

Written by: Bryanna Raiche

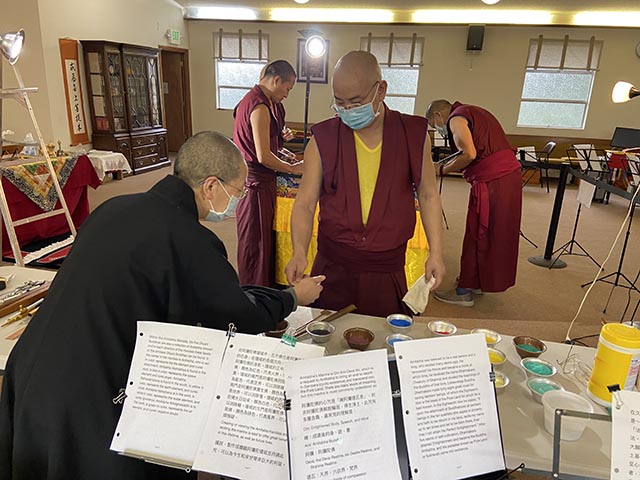

Sister Jendy and one of the lamas confer about how the sand mandala is to be created.

Photos by: Bonnie Kosmyna, Bryanna Raiche

An inventive Taiwan-born Buddhist nun, who now leads a small nunnery just east of Seattle, has been bringing the logic of Tibetan Buddhism into her arena of Chinese Buddhist scholarship and practice.

Bhikshuni Jendy Shih, who leads the American Evergreen Buddhist Association Chi Yuan Temple in Kirkland, Washington, primarily works as a dharma teacher, and as an editor, translator and transcriber. More commonly referred to as Sister Jendy, she speaks of her work as a living study of the materials — supportive of her own training, as well as that of many audiences.

One of Sister Jendy’s central intentions is to bring Tibetan logic training to Chinese Buddhist tradition. As part of this work she has transcribed or edited teachings of Tibetan masters into Chinese, based on “Learning Maps” designed by Zilkar Rinpoche. Some of her work can be found online in Chinese at Lamrim World, which attracts thousands of visits, reflecting the strong demand for access to the teachings.

The Tibetan Buddhist methods of logic, through education and debating, have particularly captured Sister Jendy’s appreciation from her years of observation. In Tibetan tradition one develops discernment, which she said strengthens one’s faith.

This potential for faith well-grounded in reason has inspired Sister Jendy to focus much of her work on making Tibetan teachings more available. The eight-day sand mandala visit to the Chi Yuan Temple in November, by a group of a group of Tibetan monks from Drepung Loseling Phukhang Monastery, is indicative of this strong connection between traditions.

From Nov. 3-11, the monastics offered teachings to the public, and completed an intricate mandala made of colored sand. They created the mandala by patiently sifting tiny sand granules onto the mandala with special tools; hollow metal rods held in one hand like a pencil. These rods are ribbed on one side, and when those ridges are rubbed by another metal rod held with the other hand, the sand is gently vibrated out onto the design.

At the end of the week the mandala, so painstakingly created, was ceremoniously destroyed – a symbol of one of the three marks of existence: impermanence.

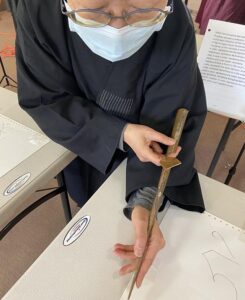

Sister Jendy was a gracious host, sitting with visitors to answer questions or setting them up with tools loaded with dyed sand so they could test their own skills by tracing Tibetan and Sanskrit symbols. Her presence offered a characteristically Buddhist balance of calmness and brightness.

In other aspects of her work Sister Jendy has translated books from English to Chinese, including “Life of the Buddha: According to the Pali Canon,” by Venerable Bhikkhu Ñanamoli; “Venerable Father: A Life with Ajahn Chah,” by Paul Breiter; and “Pure and Simple: The Extraordinary Teachings of a Thai Buddhist Laywoman,” by Upasika Kee Nanayan.

She has also worked on translations of teachings of the vinaya, the Buddhist monastic rules and precepts. One example was a translation into English of the teachings by Venerable Bhikshuni Wu Yin, which was published as “Choosing Simplicity: Commentary on the Bhikshuni Pratimoksha.” Sister Jendy also transcribed teachings by Vinaya Master Bhiksu Benyin, which were later published in English as “Karmans for the Creation of Virtue: The Prescriptive Precepts in the Dharmaguptake Vinaya.”

Her contribution to the Buddhist world carries with it an ancient monastic task – collecting and sharing the oral teachings of Buddhist masters – supported by highly modern methods. She spends days at a computer using sophisticated software, sometimes negotiating with developers on new features to improve her work.

A complex path to the dharma

Sister Jendy originally found the dharma in a way that may resonate with many Westerners: as a convert to an unfamiliar religion. This may be surprising given that she’s from Taiwan, where Buddhists make up 26 percent of the population, though that falls a good measure behind the approximately 43 percent who practice Chinese folk traditions.

Sister Jendy’s mother came from a family that blended the two, Buddhism and folk religion, making the mother critical of what she saw as superstitious practices. Inspired by the kindness and generosity of local parishes, which were led by priests mostly from foreign Christian countries, Sister Jendy’s mother converted to Catholicism before starting her family. In doing so she joined the minority 1 percent of the Taiwanese population who are Catholic, and the 6 percent who are Christian. And so, Sister Jendy had a Catholic upbringing.

When Sister Jendy was in the fifth grade, the older sibling of one of her friends announced that she was becoming a Catholic nun. Something about this resonated deeply with Sister Jendy; a seed was planted. She became certain that one day, she too would become a nun.

When she reported this decision to her devoted mother, the mother was overjoyed to imagine her daughter growing up to become a “sister.” This vision of Sister Jendy’s future became a constant thread through her youth, a subtle knowing that was always in the foreground of her choices.

Sister Jendy carried that seed with her as she went to college to become a teacher, an education she felt would be useful training for a nun. As a student looking to for ways to prepare herself to be an educator, she joined the Great Wisdom Society, a Buddhist student organization.

Though she retained her Catholic religion, she became highly involved in meditation and the events held by the group. Over time the dharma became increasingly resonant for her, and the summer before entering her senior year she took refuge and officially become a Buddhist.

After her schooling, Sister Jendy began teaching at Xingang Junior High School. But after only 18 months the pull of monastic life overtook her. She decided to go forth and take robes, finally sprouting the seed that had been germinating within her since fifth grade.

Two years later, in 1983, Sister Jendy obtained full ordination as a bhikshuni. She moved to the U.S. in 1987, where she built upon her education degree, in 1998 obtaining a doctorate in education from the University of Washington.

While the transition from dedicated Catholic to Buddhist monastic evokes images of a sensational internal upheaval, Sister Jendy conveys no such drama. She said she never felt deep religious devotion to Catholicism, but rather was a witness who enjoyed observing everything about the tradition.

Today she is still very much an observer, which is also a useful skill in Buddhism. When asked what she has observed in Buddhism, she doesn’t have to ponder her answer. She said she sees Chinese Buddhism as a tradition where one becomes part of a whole, “like a bee.” In contrast in Theravada, one focuses on a simple Buddhist lifestyle, and on meditation, suttas, and taming the mind.

Sister Jendy’s work reflects the preciousness of Buddhist monasticism, which often requires profound skill, training, intelligence, and dedicated effort over many years, and which is generously offered for the benefit of all beings, with remarkable humility.

As we appreciate the quiet dedication of Sister Jendy’s contributions to the Buddhist world, may we not only benefit from the wisdom of the teachings offered, but from the inspiration of a model of right livelihood.

Bryanna Raiche is a Buddhist practitioner who has been wooed by the Theravada forest traditions. She hails from the northern Minnesota woods, works in nonprofit management and operations, and enjoys long walks to Puget Sound with the dhamma. You can find her among the people of the beautiful Clear Mountain Monastery community.