Refined Mindfulness Program Helps Weight Loss

Written by: David Arterburn

An illustration of how habit loops work, with the three main components: trigger, behavior, reward.

Mindfulness techniques developed using a web-based platform in a new study, are helping adults meet weight loss goals and reduce unhealthy eating.

While the program is backed by medical research, it is also aligned with the Buddha’s 12 links of dependent origination, which show how we’re trapped in a repetitive cycle due to our attractions and our habits of acting on them. More on that later.

Achieving and maintaining weight loss is a major challenge for many people. My colleagues at Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute in Seattle, and Brown University in Rhode Island, recognized a paucity of weight-loss programs to help people change reward-related eating behaviors. These are patterns of eating that focus on food as a reward or an escape from negative or uncomfortable emotions, instead of in response to real hunger cues.

Since so many weight loss diets are not sustained – leading to weight regain – we hope that training people to use mindfulness to address reward-related eating behaviors, can improve long-term success rates.

To address this gap, we developed a mindfulness intervention and recruited participants beginning in April of 2022. We reached out to Kaiser Permanente Washington health plan members between the ages of 18 and 65, across Washington state, who were interested in using mindfulness for weight loss.

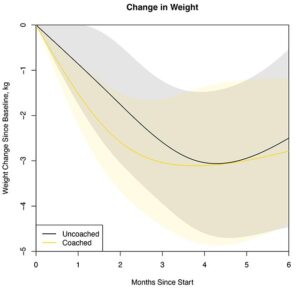

We split the participants into two groups. From July to December of 2022, both groups used the Eat Right Now platform the Brown University team developed, to help people learn about and practice mindfulness around eating. One group received additional coaching from Kaiser Permanente Washington staff, on how to apply the mindfulness tools and techniques.

At the end of six months both groups had lost weight – averaging 4.3 percent loss for coached participants, and 3.6 percent for the un-coached group. All participants reported a significant reduction in reward-related eating. Although the weight loss seems small, it will lead to health improvements for many people, particularly if it can be sustained long-term.

Mindfulness has shown promise in helping people address behavioral patterns known as habit loops, which have three main components: a trigger, a behavior, and a reward. Once the brain connects a behavior with a reward, it develops an emotional memory that reinforces that behavior in the future.

When we encounter a specific trigger (for example, free donuts at an office party), the habit loop kicks in and our behaviors can act on autopilot. Before we know it, we’ve eaten one or two donuts.

We know that highly processed foods high in sugar, fat, and salt can trigger a release of dopamine in our brain, which is similar to the impact of someone consuming substances like cocaine. Most of us live in environments where processed foods are readily available, and we see constant advertisements for them. When we see an ad that triggers a craving, eating the food is about making that craving go away or making us feel better, instead of nourishing our bodies.

The reward – temporarily feeling better, or being distracted from something negative – further reinforces the habit loop.

This way of understanding how our behavior changes is rooted in the Buddha’s teachings about dependent origination. It explains a cycle of 12 cause-and-effect links, essentially saying, “This happens because that happened. This doesn’t happen because that didn’t happen.”

When we experience something like the smell of chocolate, our mind interprets it based on what we’ve experienced before, a form of “ignorance.” This creates a “feeling tone” —a sense of whether it’s pleasant or unpleasant — which leads to desire for the good stuff to continue, or the bad stuff to stop.

Acting on this desire strengthens our sense of self or attachment. The consequences of our actions launch the next cycle of this process, known as samsara or the round of rebirth.

Kaiser developed a novel approach to coaching participants, using an app with a coaching chat feature implemented by the Eat Right Now team. Kaiser staff conducted weekly chat-based coaching check-ins, to help participants implement behavior changes.

Judson Brewer, a psychiatrist, neuroscientist, and mindfulness researcher at Brown University, was the senior author on the study. He is also the author of the forthcoming book The Hunger Habit. Brewer has extensively researched mindfulness and habit loops, and his team has found that it’s possible to undo them, using mindfulness techniques that teach people to pay attention to their cravings and triggers.

“Our approach has been a bit counterintuitive,” Brewer said. “By helping people see and feel how unrewarding overeating and other habitual eating behaviors are, the reward value drops in their brain, making it easier to change behavior.”

The Eat Right Now program provided participants with brief, daily video and audio lessons that were accessible through a mobile app or website. They received reminders and guided exercises, and had access to weekly Zoom calls for additional learning, as well as an online community for peer support. Our research team added weekly readings and worksheets to the Eat Right Now program, to help participants engage with the materials.

The lessons focused on mindful eating and other core mindfulness practices. Participants learned to pay attention to the why, what and how of eating. They practiced identifying mental states that triggered eating without hunger, and the foods they most frequently ate when triggered.

Guided exercises focused on awareness of different feelings of hunger, fullness, and satisfaction. Participants practiced core mindfulness techniques like body scans, guided breathing, and walking meditation.

The program used a three-step approach. Step one focused on increasing awareness of a habitual behavior. In step two, participants learned to recognize the unconscious rewards that they associate with those behaviors; for example how they felt after eating a certain type of food, and noticing all outcomes, both positive and negative.

Step three emphasized learning to exist with behavioral triggers without acting on them. Instead participants explored alternative behaviors such as mindfulness practices, which provides a “bigger, better offer” than our old habit patterns.

In our qualitative interviews with participants, one person said, “The whole process of habit loops was a new concept to me and I never would have thought of that. Just being introduced to a new idea and approaching things from a different take, was really the thing that made it successful for me.”

It’s exciting to see that this program was engaging and supportive of participants’ goals. Going forward, we hope to test these interventions in people who are getting other weight loss treatments like medications and surgery, to see if mindfulness can help support their long-term success.

This study was funded by a $50,000 internal grant from Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute. Looking ahead, Dr. Brewer and I are hoping to secure additional federal research funding, to support a larger-scale study investigating the longer-term outcomes of the Eat Right Now program for weight loss.

We also hope to study whether this program can help people who are using medications and surgery for weight loss to keep their weight off long-term, and reduce the risk of major health problems.

David Arterburn is a is a general internist and health services researcher, who focuses on finding safe, effective, and non-stigmatizing ways to treat obesity. He is a senior investigator at the Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute, and an internal medicine physician with Washington Permanente Medical Group. He practices mindfulness meditation with Clear Mountain Monastery and the Seattle Insight Meditation Society in Seattle.