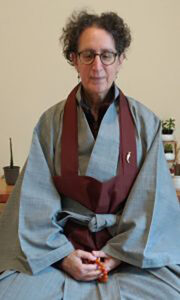

A Zen Elder Leaving Seattle, Shares Her Wisdom

Written by: Zen Master Jeong Ji

Zen Master Jeong Ji, also known as Anita Feng, is moving on from nearly 30 years of dharma and art in the Northwest.

Photos by: Northwest Dharma News archives

Editor’s Note: Zen Master Jeong Ji, also known as Anita Feng, has for nearly 30 years enrichened the dharma life of many in the Northwest, with her teaching, leadership and art. Now she’s moving on to head a Zendo in Albuquerque, New Mexico, and to be with her daughter there. She and her husband Nick Feng will retain their Issaquah home. Before she left she shared some of her wisdom and perspective about the evolution of the dharma in this region, with Northwest Dharma News Editor Steve Wilhelm.

NWDA: Please describe your dharma roles in the Northwest

Anita: When I first moved to this area, I came as a dharma teacher, the first level of teaching authority in the Korean lineage tradition. This was 1995.

I practiced with the Blue Heron Zen Community, which used to be the Dharma Sound Zen Center when I first joined. I studied with Zen Master Ji Bong, and then in 2008 he gave me Inka, which is the authority to teach koans. In 2015 I received final transmission, the authority to be a guiding teacher, in which one is officially called a master.

Before moving here I lived at the Providence Zen Center for three years, with Zen Master Seung Sahn. He was a young teacher, in his 40s. His health wasn’t great, but he was very vigorous and quite impressive as a teacher at that time.

NWDA: How did you come here?

Anita: Before coming here, we were living in Illinois. My husband was working for a company that was bought out by Microsoft. We got the call: “How do you feel about living in Seattle?” We thought about it for about two minutes.

NWDA: Now you are the teacher in residence. How is it in terms of moving up?

Anita: I did not aspire to be a teacher by any means. In fact, I left the Zen Center in Providence when I saw how hard the teachers worked and how it consumed their lives. At that time people who were becoming teachers were also trying to work full time and start families, and I could see that was the last thing I wanted to do. I wanted to be in the world and live an ordinary life.

NWDA: How has intensity changed with the passing of the founder?

Anita: That’s a really good question to bring up because I think that the way you put it really signals how the community and the methodology of teaching and practicing the dharma had to change. When the founding teachers came from Asia, most of us knew nothing about Asia, for one thing, and we knew nothing about Buddhism. There was definitely a guru kind of feeling that we all had.

NWDA: What was the focus of the instruction?

Anita: We had to be educated in all the basics of meditation. But it seemed like we were also learning how to be decent human beings.

NWDA: How was this defined by the fact that you were in the 1970s?

Anita: Many of us were hippie-style people and we were playing with a lot of freedom, not realizing we were playing with a certain amount of dynamite. And so I am grateful for the somewhat small but very vital part of Buddhism that is related to Confucianism. I learned some manners at the Zen Center.

NWDA: What about ethics?

Anita: I learned some ethics, but I left before I understood that those ethics had been broken by the teacher, Master Seung Sahn. Even though I didn’t know about the ethics problems at the time, I could see this guru type of feeling that students had toward the teacher.

NWDA: What did you feel?

Anita: Ohh, I just felt, “This is wrong.” I think that I’ve always been a very independent person, and the Zen center made me strong. Actually, the practice made me strong. Maybe that’s a better way to put it. I had developed trust in my own sight.

NWDA: What can you say about the teacher role?

Anita: Everyone is a teacher. Everyone is a student. And the first job of any teacher, if they’re worth their salt, is to be first and foremost a student of the moment of this situation and of the community. So I begin with knowing nothing, and I can do that pretty easily. With all honesty, I think that what the practice has given me over the years is just a growing comfort in not knowing.

NWDA: How does your art and pottery fit into your dharma? How has the interweaving been for you?

Anita: Oh, Zen is art. It is because you’re sitting there in silence. You’re letting your mind quiet. You’re resting in openness to the totality of the present moment. It’s what we as artists might call a blank canvas, or a blank page for a writer, not rejecting anything.

NWDA: So this is a lot like mindfulness in a way.

Anita: One of the things as a teacher that I’m trying to encourage people to do, is to accept and acknowledge. So there’s both: this wide spacious awareness, and this very detailed moment-by-moment mindfulness.

NWDA: That’s beautiful. And what about the pottery part? How does that fit?

Anita: Pottery was my first Zen master for sure. I love throwing on the potter’s wheel because there is this spinning mass of clay that’s out of control, all wonky, and it’s terrifying because you have to somehow bring it to the center.

If you are holding your breath you get tight, and then you can’t be flexible enough to know where the clay is and to bring it on center. I learned how to breathe by throwing pottery. I learned how to pay attention. One moment of inattention, the pot goes off the wheel.

NWDA: Has pottery helped you, in your practice, having this tactile way to express the dharma?

Anita: Zen is experiential. Although words used to describe the teachings are wonderful and can be signposts along the way, of primary significance is direct experience and embodiment of the dharma. The physical act of throwing on the wheel, breathing while I’m throwing, being flexible while I’m throwing, also becomes a manifestation of the dharma.

NWDA: How has the Northwest dharma scene changed? How was it when you arrived? What is it now?

Anita: Well, it’s interesting to me how technology has changed things for dharma centers. While people can access teachers and teachings much more easily, what I’ve noticed at the Blue Heron Zen Community is that there has been a growing hunger for direct connection with the sangha.

I think that technology has brought us together in many ways, but it’s also made us more lonely in other ways. Now that sanghas are open again for in-person practice, our numbers have grown, and on a Sunday morning practice, the dharma hall is full.

NWDA: It seems that in the early years sanghas were more separate from each other, and people more siloed in particular traditions.

Anita: I agree with you completely. It strikes me that it’s a natural phenomenon that we would start that way, because all we knew about the dharma was from the teacher who came over, and the tradition we happened to land with. But now, because of technology and because of the growing number of teachers, we’re exploring more and we’re finding that we have a lot in common.

And just because one lineage tradition wears gray robes, it doesn’t mean that we can’t practice with people who wear black. In fact, this is the experiment that I’m doing right now by leaving Seattle to teach at the Albuquerque Zen Center, which is in the Japanese Rinzai tradition. I celebrate this development. To me it hearkens back to the golden era of Zen in China, the Tang Dynasty, when there was a lot of wandering among the Zen students and teachers.

NWDA: Are the new people coming into the dharma internalizing their inner direction differently than 20-30 years ago?

Anita: I know that some teachers feel that there has been a big change from when you and I started practicing. Most of us wanted to have this awakening experience, to get enlightenment. It was an amazing concept.

It’s still there, but something that the younger-generation newer students have over us is that they’re a little more sober. They’re not so focused for the most part on having a big awakening, and I would credit the teachers in our generation for shifting that emphasis. We don’t present it as some kind of magic bullet, because we’ve seen enough abuse from teachers to know better. Just because you have an enlightenment experience that doesn’t guarantee anything, because ultimately you have nothing.

NWDA: How has your style of teaching koans changed?

Anita: The way I teach koans is different from the way I was taught. Koan practice was pretty macho as it came from Asia. I take a different approach, one that’s gentler and more generous with time. We’re in dialogue together. Essentially we’re practicing being in relationship, with clarity and authenticity.

NWDA: How is the role of women in dharma changing?

Anita: Well, I think that’s something that remains hard. There’s a way in which the expectations of Zen students, without realizing it, are aligned with a certain aggressive spirit, so that if I talk softly in a dharma talk, maybe it’s subtly devalued in some people’s minds. I don’t carry a big stick.

NWDA: Yeah, you’re supposed to be this fierce Rinzai master and you’re kind of not.

NWDA: What about training new teachers?

Anita: The training of new teachers is going to have to be different than it was in the past because in that world, in the koan tradition, Rinzai and the Korean version of that, this was a process that took decades and decades, and that’s not sustainable. How do we make new generations of teachers, in a reasonable amount of time?

NWDA: What about the importance of retreat?

Anita: During the pandemic we had to modify our retreat schedules so they weren’t so long, because it’s just impossible if you’re doing this online. So we shortened the retreat hours each day, simplified the rituals and chants. I think it’s going to be hard to go back to the longer form. However, if you appreciate and know that you have a limited amount of time, you can make a firm decision to not waste any of that time. Then any kind of retreat will be of value.

NWDA: What is the role of practice in changing the world?

Anita: There are so many ways that we can, as practitioners, effect change. So many people who come to this are in despair over the way the world is. Every human being going about their daily life, if they can do so with clarity and compassion, can change the world.

NWDA: What do you think of the role of teachings on rebirth?

Anita: It’s an interesting thing about rebirth. Because of the Buddhist experiential insight of impermanence and non-self, we see that everything is changing constantly, every cell in our body. There is nothing fixed. What is being reborn is consciousness, or the way that we look at what is being reborn, moment by moment. The whole universe is continually being reborn.

Zen Master Jeong Ji, also known as Anita Feng, has for 29 years enrichened the dharma life of many in the Northwest, with her teaching, leadership and art. Now she’s moving on to head a Zendo in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Before she left, she shared some of what she sees.