Profile of a Poet: Linda Greenmun

Snow

All night it fell

like a cloud-shaped bear

lounging, piece by piece,

over this roof and that

hibernating in hedge rows

weighing down garden kale

reminding us how we’re not

separate, but linked by

what we do, and don’t know:

capped chickadee with a seed,

pileated woodpecker–

its cries a drift in the hush.

Snow "lounging, piece by piece" in poet Linda Greenmun’s Camano Island backyard.

Linda Greenmun is a poet and Buddhist who lives on Camano Island, Washington. She is the author of Wheel of Days. Her work can also be found in various journals and anthologies. In 2003 she was awarded a Washington State Arts Commission/Artist Trust Fellowship in poetry.

Recently she took the time to respond to questions about her practice and work. Of her answers she says, “I hope they clarify, to some degree, who it is who writes a poem.”

What is the relationship between the practice of poetry and the practice of Dharma as you know it?

I’ll begin with the mantra, from the "Prajnaparamitra" or "Perfection of Wisdom" Teachings:

TAYATHA GATE GATE PARAGATE PARASAMGATE BODHI SVAHA

GONE BEYOND. GONE BEYOND. GONE COMPLETELY BEYOND.

THIS IS THE BUDDHA-MIND. SO BE IT.

This serves as a guide for my practice of Dharma and, also, for the creation of poetry. We go beyond ordinary form and speech and mundane concerns to experience our more essential Buddha-mind as we engage in daily practice and as we attend the Buddha’s instruction, illuminating the path. Of course, this is no easy task, and is more a process rather than being a goal. Likewise with the creation of art, we break through what is experienced so that what occurs serves as a learning device, a tool to take us deeper and below the surface. We allow this work to teach us something which we did not know with the initial encounter, as we unfold our relatedness with others and with the natural world.

You have cited Venerable Christine Skarda as one of your teachers and mentioned that her reflections on the philosopher Wittgenstein served as an inspiration for your Snow poem. Could you tell us more about that?

Just as Tenzin Jesse from the Seattle Bodhiheart Sangha has translated “The Heart of Wisdom” and Maitreya’s “Ornament of Clear Realization,” and as she and Venerable Dhammadinna have instructed students on these texts in their “Nalanda Seminars,” Venerable Christine Skarda serves students all over the world via the internet. Most recently, Christine delivered commentaries on His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s text How to Practice. She is a philosopher as well as a Buddhist nun and, except for her lectures, lives in solitude and meditation.

Venerable Christine has discussed how reasoning and analysis (the use of wisdom) have been a key for her development of compassion. She was trying to illuminate how the background pictures that we take for granted in this life (for example, that the world was flat in the seventeenth century)—referred to by Ludwig Wittgenstein in his notes “On Certainty”—how these background pictures need to be questioned. She used this example to encourage students to reexamine what His Holiness advocates in How to Practice, in the chapter on the morality of helping others on the Bodhisattva path. Here is a quote from her commentary:

“…The morality of helping others, I believe, directly challenges, or indirectly challenges this background picture of ourselves as private, essentially isolated individuals. All of these practices that His Holiness describes—of equalizing and exchanging ourselves for others—indicate that our pictures of ourselves need to be changed if we’re to develop real compassion. And the way to change it, it turns out, is to use analysis and reasoning. Just like changing the picture of the world—that we held prior to the seventeenth century—involved a change of ideas and analysis, reasoning and so on. So here, our picture of ourselves will undergo change if we use analysis and reasoning. And, when we change the underlying picture we have of ourselves, our attitudes towards others, our interactions, our feelings will all automatically change—because the picture is the thing that determines the kinds of feelings, interactions, beliefs, and thoughts we can have…”

The above quotation, of course, parallels what His Holiness extends to students when he addresses the topic of Dependent Arising. When I heard, transcribed, and reread Christine’s commentary, I believe it inspired me to see the snow in a different way—as a quiet exclamation:

“…reminding us how we’re not

separate, but linked by

what we do, and don’t know…”

"Portrait of Grandma" by Melanie, age 6. At the time Greenmun had shaved her head in mourning with all the war in the world and what she saw as many back steps in regard to women's and minority rights.

Given the idea of anatta/anatman or “no self”—who writes your poems?

It is true that I am not “inherently existent” from my own side—though this is the background picture with which we usually operate. So it is refreshing to study emptiness and begin to change the false picture, to begin understanding that we are simply mind-body parts which are the effects of karmic causes and conditions that we have created—that we are composites, which we label and cognize—this is part of our ultimate reality.

And, yet we function—this explains our conventional reality—our interdependence with all other. I write a poem or practice Dharma because of the presence of all other being. So the poem or meditation practice depends on the effort of all beings—from all being, in the verbal sense of the word. Yet, a particular poem also requires my particular aspect of this very being.

As I have learned from Venerable Dhammadinna when she taught on emptiness and asked students to think in terms of walls (another way of understanding background pictures or each pre-judgment that helps us to operate a bit more smoothly in the everyday world)—the walls, as if they existed in layers, start peeling away. We start peeling them away and we are left with a more expansive view, more openness, a fullness of experience, as we begin to view the world and ourselves in terms of emptiness.

What are your “sources” and what does life give you to work with?

Thank you for such a great nudge of a question. This leads to a quote, coming to you directly from 2500 years ago, from the time of the Buddha, via e-mail. As Venerable Dhammadinna has written to her students (quoting an article by Narayan Grady, Buddhadharma, Spring 2004):

The Buddha called karma the light of the world because it clarifies the path.

I have placed this quotation on the mirror in the bathroom to remind me about how lucky I am to face difficulties. Here are three examples: to have broken my hip and then to have discovered that my Vitamin D level was too low. Though it took a year to fully heal, there was more meditation time. And I no longer have to take allergy medication with the normalizing of the vitamin level—thus my mind is more alert.

When the most horrible dreams come, about being surrounded by beings who are physically suffering and I do not have any way of helping them, I remember to be grateful and try to learn what my dreams are teaching me, what my Gurus—His Holiness the Dalai Lama, Venerable Christine, Venerable Dhammadinna, and Tenzin Jesse—are trying to connect me with when I attend to their teachings. That is the first point.

Secondly, for me, there are children—to see through their eyes is quite refreshing for those of us who love them!

The last example is the snow from this past December—18 inches and I was unable to go very far for a week. Yet I found how little is needed to be happy and to find a poem, how confinement means more time to study, how the hush is just right for contemplation.

Is there such a thing as a “Buddhist poet?”

Very definitely, a Buddhist poet may exist, at least in the conventional sense of the term. Ultimately, we are just passing bubbles, energy taking one compositional form or another—only beyond this is our endless, boundless Buddha-nature—the bliss of which may only be experienced briefly in this life, for me at least, in sitting practice.

Here are a few verses from one Buddhist poet, Jane Hirshfield—the last two verses from her poem The Weighing:

…So few grains of happiness

measured against all the dark

and still the scales balance.

The world asks of us

only the strength we have and we give it.

Then it asks more, and we give it.

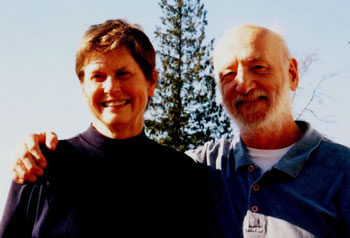

Linda Greenmun and her husband, Renny. They learned more from their children "than we ever taught them."

How did you come to the Northwest, to poetry, to the Dharma, to your particular teachers and practice?

Forty-two years ago my husband Renny accepted an administrative position from Pre-College Testing, located at the University of Washington. We traded the hot, dry flatland, the scrub-cedar and blue sky of Fort Worth, Texas for the Seattle area’s mountains and waterways, its fir and cedar forests and gray sky.

Though I had completed Nursing School and become a Nurse Anesthetist by 1967, my early years after the move to Washington were focused on caring for our young children. Renny and I did not grow up under very healthy conditions—he always says that we learned more from our children than we ever taught them. And this is true.

We followed Shaun, who loved the natural world and found strengths in people we did not understand, until we had known the same people for quite a long while. Chris embraced whatever came his way and taught us to create our own happiness. We were going to confine ourselves to two children, then had an opportunity to adopt our only daughter—she taught us to love people, to laugh together as we rolled down a grassy hill and to support each other during not-so-easy times. She was born three days after Christopher—we named her Christine and they grew up as family twins. Aaron inspired us to welcome, as he did, every difficulty and see what was on the other side, to discover possibilities we had not dreamed existed for us. Renny and I now have eight grandchildren—two for each of our children.

Mostly, I worked part-time at Group Health, Virginia Mason and the University of Washington. As the children grew older, I worked on a degree in English Literature and Creative Writing, somehow managing to finish. Nelson Bentley introduced me to his Poetry Workshops, where I began to focus on this genre.

On February 14th, 1999, I took refuge as a Buddhist from Venerable Thubten Chodron, who has since founded Sravasti Abbey in Eastern Washington. I was inspired by my son Chris, who is peaceful and wise. He gave me Venerable Chodron’s name. However, by the time I wanted to do the preliminary practices she was very busy with travel and thoughts of the abbey. Eventually, I found Venerable Christine and then rediscovered my old friend Tenzin Jesse, who had returned from India. She introduced me to Venerable Dhammadinna.

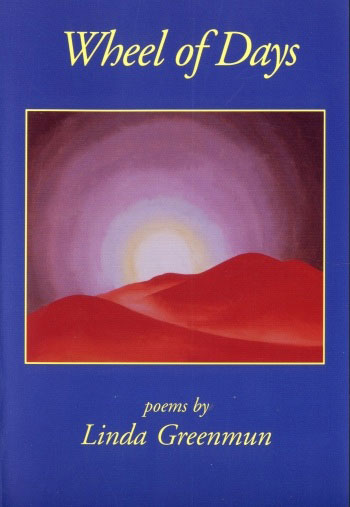

In 2002, Floating Bridge Press published a book of my poems that I titled Wheel of Days. Its publication was made possible in part by a Fellowship in Literature awarded by the Washington State Arts Commission and Artist Trust.

How have you chosen to use sales of Wheel of Days to benefit others?

Peter Pereira and the other editors gave me 500 copies to sell to raise funds for Tara’s Gate—a transitional group to support Buddhist practitioners returning from prison into the community. Tara’s Gate could not be sustained for lack of donors, though we were able to assist a few people. There are still two boxes of Wheel of Days remaining.

If anyone would like to have a copy, please let me know: lindapg@verizon.net. I shall send you a book with a bookmark of the Snow poem and you may donate the $14.00 (the original cost) or any amount you are able to give, to one of my teachers or to the Freedom Project (which teaches non-violent communication in communities, including prisons) or to Enso House (a Zen Hospice on Whidbey Island where I volunteer as an RN.) If you prefer, the donation may go to the temple or Dharma Center of your choice.

Also, let me know if you would like comments on your own poems. In exchange, you could donate to one of my teachers—most donations are tax-deductible.

May the all-Embracing Ones continue to inspire and bless us, as we try to remove our obstacles to Buddha-mind, practicing this path. Many thanks to each reader…

LG

An Accord

Touch without touching, enchantment with light,

Nathan’s hand presses against the glass, wants

Grandpa’s hand flat, pushed on the other side

of the window before they open the door.

Fifteen months, he holds the larger hand, drawn

by dog, bird, tree, young voice testing sound

with each greeting. Night, he returns home

with his father. Grandpa looks for smudges

on windows. They point out chime, leaf,

daylight’s departure hinged on return.

L. Greenmun

April to December, 2007

Mat Woven in Winter

Ruby for fall leaves tipped with gold,

Matted under the maple. Jade

For Douglas Fir. The pumpkin field’s

Orange plowed, covered with fog–patch,

Rows now bear snow-geese, white necks

Turned back on fluffed back-feathers.

Blue and purple for evening sky.

Five years old, Melanie’s quick

To learn over and under–tulips’

Pink are banked against yellow

Daffodils. Her gift reminds

Us, how each season dips in and out,

Enfolds what it’s not, how we do not

Stand apart from others in the world.

L. Greenmun

(Last two lines revised since original publication,

Manzanita Quarterly, Spring 2004)

Contributors: Linda Greenmun, Julie Welch.

Photos: Renny Greenmun, Caterina De Re.

Art: Melanie Greenmun.