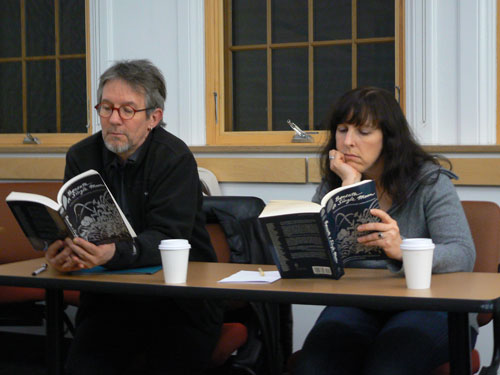

Ed Lorah and Shannon Callin contemplate a poem.

Zen and American Poetry Class:

Seattleites Read Poetry, Rain Falls

Question: What did the Zen poetry teacher email his students?

Answer: No attachments.

Thus began my efforts to supplement readings in Beneath a Single Moon, an anthology of spiritually influenced poems, with other poems and prose works. My momentary lapse in attention was almost immediately brought to my attention. In the blip of an internet second a reply popped into my inbox from Tamar, one of 10 students sharing this winter seminar class, delivering the joke above.

Our Zen and American Poetry class was an eclectic mixture of people from their early 20s to late 50s, coming together once a week to explore poetry in English, both historic and contemporary, and its relationship with Zen Buddhism. Some of us had extensive backgrounds in poetry, literature or Zen. Others were curious and just starting to explore. In investigating either tradition, or studying their mingled waters, there is no bottom.

We met in Savery Hall, a building at the heart of University of Washington campus in Seattle. It felt appropriate that the East Asian Library was across the lawn. We met after dark, not able to see the beautifully arrayed Yoshino cherry trees outside the classroom windows. But inside we read poems aloud, sat brief periods of zazen (Zen meditation) together, and went around the circle discussing poems and poetics, a practice that itself is hundreds, perhaps thousands, of years old.

I was inspired to offer this class due to three passions, three roots: Zen Buddhism, poetry, and a desire to teach a non-required class on my particular interests to students interested in exploring, not simply fulfilling a requirement.

Course leader Ewan Magie, in a light moment.

The course emerged out of my own Buddhist practice within the Zen and vipassana traditions. My relationship with literature and the arts is changing as my practice deepens. I wanted to explore this territory with others who might share a similar interest.

The rich relationship between poetry and Zen itself is deepening profoundly as it continues evolving in American culture. It is this subtle, rich, and shifting relationship that unfolded of itself in this class.

Most evenings we began with a short period of zazen, and sometimes I remembered to bring a bell along with my books. We met for a fleeting two hours just six times this term. Like the space around a poem, silence and quiet framed our entry and exit to discussion:

You ask why I make my home in the mountain forest,

and I smile, and am silent,

and even my soul remains quiet:

it lives in the other world

which no one owns.

The peach trees blossom.

The water flows.

—Li Po, translated from the Chinese by Sam Hamill.

Our first class began with this poem emerging from silence, as from the depths of time. In our modern American culture, frantic with busyness, noise, and the accelerating pace of change, this poem from China’s T’ang Dynasty feels otherworldly. Yet something resonates within us, even in this age of machines and speed. At least for those of us sharing this class on poetry and Zen, early in 21st century Seattle, there seemed to be something that is shared.

The birds have vanished into the sky,

and now the last cloud drains away.

We sit together, the mountain and me,

until only the mountain remains.

—Li Po, translated by Sam Hamill.

An apparently simple poem arranged in simple English sentences seems to resonate with something still alive in human hearts today. Perhaps there remains something in each of us that somehow knows we are not the sum of what we have done, not the noise we make. Perhaps we might become more quiet. As translator Tony Barnstone says in his essay “The Poem Behind the Poem”:

If we are very quiet [ ... ] if we become nothing long enough, we may discover not what the poem says but what it does.” (The Poem Behind the Poem, page 11).

Our class began with a Western poem too, “The Snow Man” by American poet Wallace Stevens. After it opens with a dramatic assertion, “One must have a mind of winter . . . ”, this poem, composed by a non-Buddhist American and published in 1923, concludes:

the listener, who listens in the snow,

And, nothing himself, beholds

Nothing that is not there and the nothing that is.

—Wallace Stevens, Harmonium, 1923.

I will offer this class again in the spring, through the ASUW Experimental College. Perhaps you too would like to come, to sit quietly and explore poetry and Zen together? If so, please come and sit with us as cherry blossoms bloom and fall to earth.

About the author:

Professor Ewan Magie holds a master’s degree in literary criticism from Prescott College and has been an adjunct professor at Bellevue College since 2001. In Seattle he practices with Seattle Soto Zen and Seattle Insight Meditation Society. He also practices with the Red Cedar Zen Community in Bellingham, and the Mountain Rain Zen Community in Vancouver, B.C.

Photos: Sergey Feldman